TACKLING CHILDHOOD OBESITY: A FOCUS ON ADVERTISEMENT

Some sweet data:

In 2020, 39 million children under five years old were classified as either overweight or obese. This is due to the rising consumption of sugar; data suggests an increase of over 50% per capita within the last 50 years. Global statistics specifically targeting children are difficult to obtain with full accuracy due to a disparity in national surveys (as depicted on the WHO graph above). However, as of 2015, in France, 17% of children were classified as overweight and 4% of those were categorised as obese.

The phenomenon is unlikely to decline soon as children consume a growing amount of highly processed foods, rich in added sugar, in various forms, whether as a preservative, a flavour enhancer or to add sweetness.

Furthermore, children and adults combined are less active, which can be closely linked to increased screen time. The prolonged exposure to screens – whether due to mobile phones, computers, or TVs – has been on the rise and as physical activity is credited to be one of the most effective treatments for preventing children from becoming obese, a link between obesity and screen exposure has been made. Added to the issue of children’s increasing screen time, food, and more often than not, highly processed foods are marketized and advertised on TV and social media.

Numerous factors are connected to child obesity including pricing and easiness of accessibility to highly processed and fat-saturated products. I will not consider them in detail in this article and instead, put a stronger emphasis on advertising and screen time.

Food for thought: a little treat awaits

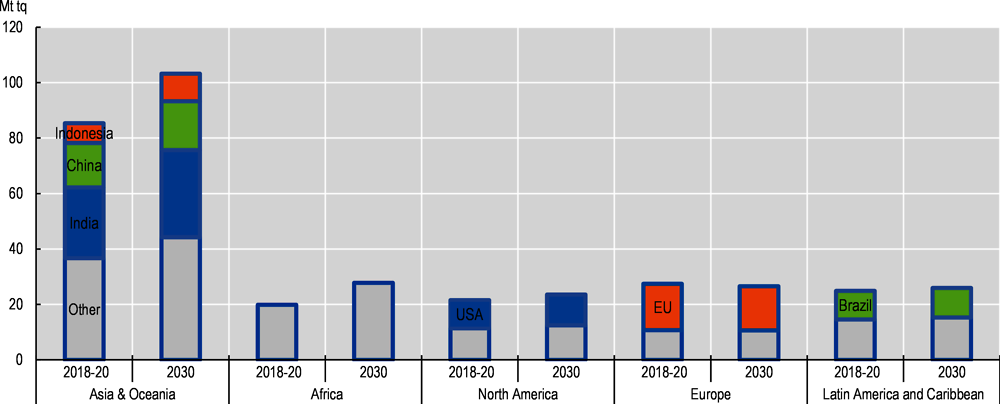

Due to rising incomes and urbanization in developing nations, the average per-capita consumption of sugar in the world is anticipated to increase over the coming ten years. By 2030, it is predicted that Asia’s consumption of sugar would increase the most and account for more than half of global consumption due to the growing demand for sugar-heavy soft drinks and confectionary items. Although population growth is predicted to be the main driver of consumption growth in Africa, consumption is nevertheless predicted to continue at levels that are significantly lower than those in Asia.

Recommendations, but who reads them?

The World Health Organisation (WHO) which aims to better the health of people worldwide regardless of gender, age, ethnicity, religion or economic situation is taking the issue seriously and has created numerous reviews and guidelines regarding the acceptable consumption of sugar. It “recommends adults and children reduce their daily intake of free sugars to less than 10% of their total energy intake”. Furthermore, the WHO emphasises the various health benefits associated with reduced sugar consumption and the necessity to find varied sources of energy throughout the day.

The stress over the requirement for the reduction of fat-saturated products is linked to the numerous risks associated with a higher BMI (body mass index) – a tool used to determine a person’s health in relation to its weight, differentiating obese from overweight. The most common associations between elevated BMIs are made with hypertension, diabetes and cardiovascular accidents, however, there are numerous other potential implications, especially regarding childhood obesity. Children are not only at risk of premature death and potential impairments, but they can also encounter hypertension and fragile bone structure leading to fractures and tenacious breathing difficulties. We are not loving it…

When the lollipop becomes both the carrot and the stick

There is a growing concern that consumption of products dense in added sugars, such as sweetened beverages, both increase overall calorie intake whilst reducing the consumption of foods with more nutritionally balanced nutrients, resulting in poor nutrition, excess weight, and an enhanced danger of non-communicable diseases (NCDs). At the same time, numerous regions of the world have seen the price of soda become less expensive than bottled water, resulting in a higher risk of high-calorie diets for people with low income.

A number of governments across the globe have taken diverse initiatives to stop the prevalence of childhood obesity. Those measures include various forms of sugar taxation, laws against the advertising of products deemed as unhealthy to children and the implementation of straightforward labelling on products to raise consumer awareness.

However, despite all of these efforts, childhood obesity is still on the rise and with the end of the peak of the COVID viral pandemic, statistics have revealed a worsening situation. Therefore, one might wonder about the various measures taken by governments across the planet, their effectiveness and the WHO recommendations.

Who would have thought: physical activity impacts weight gain

Research has demonstrated that long periods of physical inactivity may have a great impact on the weight of children. Those extended intervals can be the result of various factors such as homework, motorised transport – whether public or private – and screen time associated with entertainment such as video games, social media or television.

Further investigations have observed a parallel between sedentary activities and the over-consumption of processed foods with little nutritional value. It was claimed that watching TV while eating might delay the sensation of fullness and lessen the signals of satiety from recently eaten products. Moreover, parental early conditioning of their children to correlate watching TV with unhealthy food snacking also helps to further clarify the connection between media consumption and obesity. As a result, screen time may have an impact on calorie intake in addition to the replacement of physical activities with sedentary occupations, requiring a lot less energy despite a highly calorific diet.

Content consumption and minors’ exposure to advertisements are also related. For instance, sports-related marketing has been linked to children’s and adolescents’ unhealthy dietary patterns. But who can blame them? Sports are more enjoyable from the sofa with popcorn.

When regulations and recommendations feel like a stick

In 2010, the WHO set of guidelines on the advertising of foods and non-alcoholic beverages to children was adopted unanimously by the sixty-third World Health Assembly, acknowledging the fact that a sizable portion of marketing worldwide is conducted around foods high in fats, sugars, or salt. Resolution WHA63.14 on the advertising of food and non-alcoholic drinks to children called on Member States to adopt the guidelines in full and to choose the best course of action for their own countries to prevent their impact on minors.

Governments were supposed to determine the breadth of a nation’s marketing limitation given that they were considered to be in the best position to decide the orientation and overall strategy for achieving population-wide public health goals, as stated in the set of guidelines.

Multiple countries, such as Mexico, Chile, France and Hungary, have created sugar taxations to deter the production and release of fat-saturated and sweetened products. Aside from such measures, they are a few instances of hard regulations and restrictions to stop the proliferation of obesity. This is notably the case as there are only rare instances of politicians making significant attempts to take the initiative in putting the “hard” (and effective) policies advised by the WHO into action.

One well-known example is a senator from Chile named Dr Guido Girardi. Despite vehement resistance from the food business and many of his colleagues, he worked relentlessly at the political level for more than to implement food regulations, such as strong labelling requirements on healthier options, marketing limitations to boost healthy school meal policy, and levies on soft beverages.

Politicians frequently seem to assume the effectiveness of market-based and informational approaches to combating obesity, despite all evidence to the contrary. They are intimidated into inaction by actual or potential industry opposition, which might lead them to prefer focusing their political energy on other difficulties. Of course, there are contradictions, but overall, inaction rules, the obesity crisis spreads right before their eyes, and their nations continue to support the plans that WHO presents to the World Health Assembly every year. While governments have the authority to adopt strong policies and laws promoting healthier, more sustainable food systems, in practice may sometimes be very hesitant to do so.

This raises the question of “how can politicians be prompted into action?”

Some of the initiatives that have been taken include the UK ban on the advertisement of unhealthy products in online media where children make up a large portion (25% and above) of the audience, Chile, on the other hand, is more strict and prohibits any form of marketing targeting children, whether online or not.

The first initiative focuses solely on children’s programs and has been criticized for its minimal impact due to its lack of understanding of children’s television viewing trends. Furthermore, contrary to the Chilian action plan, this ban on child marketing only focuses on online platforms, leaving out in-person adverting as is the case in the picture above portraying a Burger King ad on a soccer field, where children of all ages will be playing, whilst their family will be watching, and, potentially crave for a burger afterwards.

The second initiative in Chile, although arguably more well-rounded, does little to change the children’s environment and relation to food. In a context where 2/3 of the adult population has been reported to be either overweight or obese, despite numerous marketing-based legislations, regulations will probably need to target parental awareness of childhood obesity and its correlation with the celebratory aspect of unhealthy consumption.

Therefore, childhood obesity might be difficult to challenge without targeting both the environment – with the role of food in society, and how it is consumed – and the family who might lack the awareness/understanding of the situations and risks.

Other action plans include the introduction of the nutri-score in some European countries such as France, Switzerland or Germany. This last measure despite giving the consumer easier access to the nutritional values of products has two main flows: its application is the result of a voluntary basis and has been proven to have a limited impact on unhealthy products compared to healthy ones. The reduced influence of the nurti-score on overprocessed foods and sweetened drinks has been linked to a given consumer perspective on the product and the purchase intention.

In other words, when a consumer makes the conscious decision to buy something they view as unhealthy, they do not care about the label warning them of the poor nutritious value of the product and therefore, its presence has little importance.

Kids and grown-ups might not love it so, the happy world of obesity

The issue around childhood obesity is a rampant global health issue with a severe impact on physical well-being. The growing advertisement of various unhealthy products, the reduced physical activity of people linked with an increasing time spent in front of screens and the pricing of highly-processed goods have direct consequences on their consumption. Taxations, child marketing bans and straightforward labelling have proven to have limited impact and do not seem to be enough to change the ever-augmenting curve of obesity. It may be useful to widen the target audience to the advertisement ban as is the case for alcoholic beverages in some countries, or to create counter advertisement campaigns as it has been the case for nicotine for example.

Potential points of interest to discuss with a representative of the WHO with regard to childhood obesity and the role of advertisement:

- How are guidelines being created knowing that the situation of each country can be extremely different? In the Chilian case, for example, the guidelines have been followed and the government has done extensive work to set new regulations in place and counteract the lobbying in place. In the aftermath of those new laws and knowing the impacts those legislations had, do you think it would have been useful to maybe create regional or national guidelines, which would have taken each case into consideration?

- Do you think we could see a total ban on the advertisement of unhealthy products in some countries? And would you say it is the way forward?

- Sugar taxation has been criticized to have a limited impact on childhood obesity and on the consumption of sugar in general, do you think those taxes should be increased further to force the industry to reduce the production of highly processed goods?

- Are you optimistic about the fact that we could reverse the obesity curve within the next 30-50 years?

Nikita Wissler