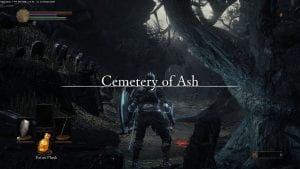

As part of the Queer Fears Network takeover of the Gender Studies Research Group Blog, we are delighted to present Scott Mackay’s entry considering Queer Identities in Horror Gaming entitled: ‘Dark Souls III and Queer Overcoming: Alienation, Isolation, and Failure.’ (Dr. Darren Elliott-Smith, blog-editor)

‘Dark Souls III and Queer Overcoming: Alienation, Isolation, and Failure’, by Scott Mackay (PhD Candidate, University of Stirling)

Introduction.

When Laverne Cox called for more trans representation in media in the 2020 documentary Disclosure, she argued this was necessary due to the effects it would have on public perceptions of trans people in a time where representation in filmic media is moving towards a more sympathetic disposition. Her words hold more than just a modicum of truth; her own role in Orange is the New Black presents her with a multitudinously layered identity as complex on the screen as it is off, made possible because she is able to draw from her own experience. As a result, her character Sophia Burset’s emotions are palpable. Cox’s prescription to Hollywood is a call to arms to the wider media world to do better in the hiring and representation of gender non-conforming identities.

It likely wouldn’t ruffle many feathers among the reading community of this blog to suggest that the video gaming industry, despite its progress in recent years, remains still the final frontier. Game development and publishing structures are neither doing enough to include gender non-conforming identities into their creation processes, nor to represent gender non-conforming identities in playable characters. These concerns, and Cox’s too, highlight a very real appetite for representation yet, deeper still, they betray uniquely queer relations to feelings of alienation and isolation. In a brief exploration of how these unique relations manifest themselves in video games we will touch upon two AAA titles: F1 2020 [1], and Dark Souls III [2]; case studies in how to, and how not to, deal with representing queer identities in video games. Both games employ character avatar customisation options, and both represent monoliths of failure in their narratives for wo/men and queer identities.

“Micro-aggressive Easter Eggs”: Uniquely Queer Relations to Normative Fears: Character Creators, not Monsters.

The feelings of fear that queer individuals experience inhabit the same locations and exhibit similar responses to that of their normative counterparts; isolation feels lonely either way. Where queer fears differ is found in the process of relation. We see this when gender non-conforming individuals are greeted with the character creation segments so common in contemporary video games and their unique experiences and identities often can’t find the space to correlate themselves to the realities of the game. It is clear that F1 2020 isn’t about progressing pro-trans public policy despite the associated championship’s vocal gesturism in its ‘We Race as One’ campaign; it’s about real racing, and real racers wear helmets. The helmet gives the game an excuse for its sparse character creation options. It offers the player as many as 20 head model options meant to vaguely correlate to a mixture of ethnicities and jaw strengths, and a few even seem vaguely effeminate, but Tatianna Calderon remains the only playable woman in the game. What is even more striking is that F1 2020 is the first game in the series to allow the player to create their own team and choose their teammates. Calderon could feasibly be given a championship-winning car in-game and guided to what would be the first world championship won by a woman. Playing the game alone wouldn’t tell the player this though; it doesn’t expect this outcome and neither did its developers. What might be termed ‘Micro-aggressive Easter Eggs’ are found in moments like this in games where a gendered expectation is betrayed. The lack of fanfare for Calderon’s ‘maiden’ championship sums up the developer’s position: even though it is a programmed reality of the game, it likely won’t happen so it isn’t significant enough to address with even a single line of dialogue to commemorate it. When those with queer identities play this game they’re not only reminded that they are the exception, and isolated through the spartan nature of the character creator’s accounting for gender non-conforming identities, but that they’re also alienated from their achievements, through the game’s omission of the uniqueness of the achievement and the weight of the collective failure of those alike that came before it. This is an example of how queer fears operate differently to normative fears relationally; the pace of the grid at the 110 AI difficulty scaling doesn’t make me feel anywhere near as alienated as the inability to exist authentically within the car, even inside a helmet.

It might feel like an unfair comparison to parallel F1 2020 with Dark Souls III, two completely different games from different sides of the industry, but both games make use of a character avatar creator which encourages the player to represent themselves within the game, and so this encouragement is made to feel disingenuous when we are also made to conform our images to their specifications. To be clear, this is a criticism of avatar creators and ‘Micro-aggressive Easter Eggs’ more broadly than in just F1 2020’s; a current fear the writer has is that the spiritual successor to Dark Souls III, Elden Ring, won’t allow them the same subjectivity through their in-game avatar. So, this is an open plea to Hidetaka Miyazaki and FROMSOFTWARE, INC.: Please let me keep putting a beard on character models that also have breasts.

Dark Souls III, Trans-Feminist Entanglements and Queer Overcoming.

Dark Souls III, and its associated series, are monoliths of failure for hordes of gamers, queer or otherwise, and while its character creator offers two gender options it succeeds in many areas where games like F1 2020 fail: the player can create a character with breasts, and a beard. The gender categories it offers correlate better to AMAB (Assigned Male at Birth) and AFAB (Assigned Female at Birth) in their operation than any imposition of a defined role within the game, or the availability of certain face shapes. The only meaningful change it effects in the game is the gender of the NPC (non-playable character) Anri, who the player character can ‘marry’[3] in the latter stages of the game, but even this can be subverted with a ring that reverses gendered interactions when worn. The character model’s face and body can look as muscular, angular, soft, or blue as the player decides, and all options for both facial and head hair, and scars are completely accessible. This is an example of a more solid approach to depicting gender non-conforming identities in character customisation options and has since been taken up by developers as influential as Nintendo EPD whose Animal Crossing: New Horizons operates through a similar framework opting even to drop the ‘male–female’ labels entirely. In employing approaches like that found in this game, developers allow for a respite from the endless stream of ‘gender-critical’ abuse that gender non-conforming identities receive by allowing space for their identities to exist within the escapist spaces provided by the universes of their games.

How Dark Souls III and F1 2020 deal with wo/men’s and queer failure radically differs; despite Dark Souls III’s notably sparse storytelling within its ludo-narrative, there is space for an embodied overcoming of this failure spurred by the collective failures of those who have tried and failed before the player character to survive the ritual linking of the fire. With an ethos borrowed from Catherine Keller’s ‘Transfeminist Entanglements’, the player’s character can be read as a nexus of intersectional ash regardless of how their avatar actually looks, especially within the character’s own ‘world’. . This narrative, and process, provides the space for them to be read as transgressive bodies visually, compositionally, spiritually, and sexually. The presence in the games of Friede and Anri, Unkindled wo/men, demonstrates that these beings born of ash can and do reflect the pre-existent modalities of gender expression held by the previous owners of their constituent ash; indeed it makes little sense to base their expression in norms associated with reproductive categories when their ‘birth’ process is considered. The Ashen One is composed of a non-binary ashen flesh that appears as it wills it to. It builds upon the collective failure of those whose ash forms its flesh, and when they finally succeed their overcoming is secured through their failure.

Dark Souls III is an example of the greater life a truly great game can take on due to the depth of how its narrative is tied to its ludo-narrative. With few exceptions, the bosses of the game grow more difficult as the game progresses.[8] This is tied to each boss’ physical, magical, or spiritual prowess as referenced within the game’s narrative. This narrative-informed ludo-narrative style can be seen where the player fights sergeants before they fight generals. The Nameless King is both punishing and difficult to kill because, as an ancient god of war and lightning, he should be. It is also likely that a king be protected by his guards, as he is. This congruency between narrative and ludo-narrative also provides a queer-inclusive space, both within how the player is able to relate to the game by allowing them to create transgressive images, and within the game’s ‘world’ by providing a narrative that accounts for these transgressive images. Within Lothric[9] there exist beings animated from pools of intersectional ash and the appearance of these beings has a propensity to reflect this intersectionality. As a result, the transgressive image of the gender non-conforming player can both be seen and allowed for in-game, promoting a respect for their own subjectivity on behalf of the game’s developers; a stark contrast to the micro-aggressions betrayed in F1 2020.

Dark Souls III’s approach to depicting queer identities in video games, if modified to reflect Animal Crossing’s dropping of the labels, would serve well any future game that intends to implement a character customisation feature, as it not only allows for gender non-conforming individuals to see themselves within their character, but also within the game’s universe itself, which fosters a deeper connection to the content and takes uniquely queer experiences of alienation, isolation, failure, and overcoming seriously.

Works Cited

Codemasters, F1 Series (Codemasters Software), F1 2020 (Birmingham, 2020).

Disclosure: Trans Lives on Screen (2020, Sam Feder, Disclosure Films/Bow and Arrow Entertainment/Field of Vision (II), USA) with Laverne Cox as main contributor.

Keller, Catherine, ‘“And Truth—So Manifold!”: Transfeminist Entanglements’, in Intercarnations: Exercises in Theological Possibility (New York: Fordham University Press, 2017), pp. 35–46.

Keller, Catherine, ‘Tingles of Matter, Tangles of Theology: Bodies of New(ish) Materialism’, in Intercarnations: Exercises in Theological Possibility (New York: Fordham University Press, 2017), pp. 60–82.

Miyazaki, Hidetaka, Dark Souls Series (FROMSOFTWARE, INC.), Dark Souls III: Fire Fades Edition (Tokyo, 2017).

[1] Codemasters have produced a yearly arcade racing game under licence for the Formula 1 World Championship since 2009 (a Wii exclusive). The intellectual property of the officially licensed Formula 1 video game however predates Codemasters’ first entry to the series in 2009.

2004’s instalment, by SCE Studio Liverpool, also features a character creation segment. There are no women in the game, and you cannot create one in this game either. Despite this, the intro cutscene features an almost James-Bondesque objectification of multiple women. One shrugs suggestively wearing a small dress on a red carpet, another is translucently superimposed in underwear alone over a cut of cars racing, but neither are racers.

Codemasters chose to remove this feature in their early instalments to the series opting to keep helmet customisation alone. It was brought back in 2017 after they overhauled the single player structure of the game.

[2] Dark Souls III is the final instalment in Hidetaka Miyazaki’s Dark Souls series (FROMSOFTWARE INC.) that began in 2007 with Dark Souls.

[3] Plunge a ceremonial sword into them on an altar in a ritual that robs them of their inner darkness and gives it to the player character. This enables a third ending to the game where the player character inherits ultimate power and dominion. Hardly a heteronormative wedding.

[4] ‘The Ashen One.’ This is how the protagonist of Dark Souls III is referred to with no name of their own. However, they can eventually accept a name in dialogue with a painter NPC: “Ash”, referring to their composition, and that which defines them existentially.

[5] ‘The Unkindled’ are one of the game’s numerous depictions of humanity. They are ‘born’ through the conglomeration of several powerful ashes that form into one unified being. The process through which this occurs is not elucidated in-game, though we do witness the ‘birth’ of The Ashen One in the opening cut scene in which they raise fully-formed from a grave empty of all but ash.

[6] ‘Linking the Fire’ is one of the final goals of the game that the player can choose. This event is specifically a ritual trial by combat fought between the challenger (in the player’s case, them) and the union of the souls of all those who have previously succeeded in besting the trial: the Soul of Cinder (‘Cinder’, the antithesis of The Ashen One). The final stage of the trial sees Cinder’s fighting style regress to that of the Trial’s founder Gwyn, Lord of Sunlight, and God of the ancient land of Lords. Choosing to link the fire after defeating Cinder gives the player the option to fuel the fire that keeps the game’s ‘world’ lit with their own soul. The trial itself is meant to determine the combatant’s soul as suitably strong enough to be used as the fuel. This process repeats cyclically roughly every 1000 years according to characters from previous instalments of the series.

[7] ‘Saint’ being a title reserved for the successful, and the memorable. Four of the major bosses are examples of ‘Sainthood.’ This itself serves as the reason for the player’s animation. The fifth refuses to claim sainthood, but the ‘world’ itself demands it and so ‘Ash’ takes flesh.

[8] I’m looking at you Yhorm…

[9] The setting of the third instalment, following Lordran and Drangleic from the first and second respectively. Both settings also feature in Dark Souls III albeit reduced, over time, to ash.

Author Bio:

Scott Mackay (They/Them) is a non-binary agender PhD researcher and drag enthusiast with interests in queer and comparative theologies, hermeneutics, gender non-conforming representation in video gaming, critical theory, and theopoetics.

They are currently participating in the first year of a PhD in religion at The University of Stirling after achieving their masters of research with a thesis in critical religion and surveillance studies. Scott is particularly proud of bringing the high adrenaline action of competition paintball to the grounds of Salisbury Cathedral in a paper presented at the 2016 Implicit Religion Conference entitled: “All are equal before the eyes of the Marshall:” Community, Charity, Paintball, and Implicit Religion.”