As the shadow of another General Election hangs over Britain, questions are still being asked about the safety of political advertising online.

The presidential election and EU referendum in 2016 sent the political world in a spin. Now, three years on, and after several scandals set around data-farming and the spreading of misinformation, social-media companies are finally making some changes.

The most recent of theses changes came from Google and Alphabet Inc., announced in the form of a blog post from earlier this week. In the post Google outlines their changes, which include curbing the people who advertisers can target to groups such as “age, gender, and general location.”

Google argue that by doing this their services fall more in line with practices from the more classical media outputs like television and print. On top of this they make clear that they will not stand for misinformation being spread through their services, but state that “robust political dialogue is an important part of a democracy” and as a result will try to keep their involvement in advertised messages to a minimum.

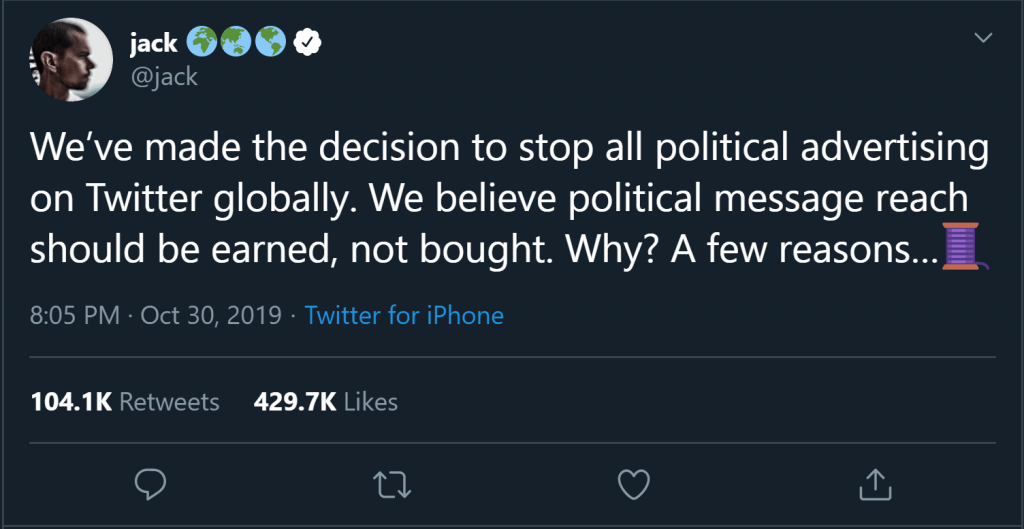

The biggest, and possibly most shocking of these changes came from Twitter at the end of last month. In a thread of tweets, CEO Jack Dorsey announced the company’s plans to put a complete stop to all political advertising on their platform.

“we believe political message reach should be earned, not bought.” – Twitter CEO Jack Dorsey

This sentiment is mirrored word for word on the sites ad-policy information section, which also outlines who, and what, is subject to the new policy. “We define political content as content that references a candidate, political party, elected or appointed government official, election, referendum, ballot measure, legislation, regulation, directive, or judicial outcome.”

This coverall policy is a fair attempt to stop political misinformation being spread through their site, but it does risk blocking information about smaller candidates, or political issues, that are not getting as much coverage, or seen as less newsworthy.

Under this system ‘News Publishers’ that are enrolled with Twitter can still advertise about political content “but may not include advocacy for or against those topics or advisors.” Showing that Twitter is still willing to spread a political message but wishes for it to be as free from any bias as possible, a feat that, given inherent bias in a lot of media, seems like an almost redundant stopgap.

Alongside Twitter and Google, Facebook has also made some changes to their advertising policies. Facebook, and CEO Mark Zuckerberg have had a hell of a time since 2016, after allowing advertising agencies like Cambridge Analytica to farm data in order to create persuasive, targeted advertising built mainly off misinformation and lies.

Since the elections, Zuckerberg has appeared in courts across the world to testify about Facebook’s policies on advertising and personal data, most recently appearing in congress last month.

As seen during both the congress hearings, and through updates to Facebook’s own policy documents, the social-media giant is choosing to take a much more hands-off approach to the sort of adverts that they will allow.

Facebook’s advertising policy guide states “Facebook prohibits ads that include claims debunked by third-party fact-checkers or, in certain circumstances, claims debunked by organisations with particular expertise.” This lax approach somewhat pushes the blame from Facebook hosting the adverts to those choosing to make the posts in the first-place. This was an update from their original policy which outlawed any posts of misinformation.

The biggest reason for this change, according to a Facebook spokesperson was, “We don’t believe that it’s an appropriate role for us to referee political debates. Nor do we think it would be appropriate to prevent a politician’s speech from reaching its audience and being subject to public debate and scrutiny.”

“We don’t believe that it’s an appropriate role for us to referee political debates. Nor do we think it would be appropriate to prevent a politician’s speech from reaching its audience and being subject to public debate and scrutiny.” – Facebook Spokesperson

Even by their own admission the third-party fact-checking system brought in by Facebook is flawed and incredibly limited, making it near impossible to justify their absence from policing the advertisements going up on their site.

These minimal alterations to policy seem to suggest that nothing has changed in the ethos of Facebook’s business plans, even after the intense public scrutiny that they have been put under after the US election and EU referendum of 2016.