To celebrate the forthcoming book launch of New Queer Horror Film and Television (UWP 2020) later this month, as part of the contributing research to the Gender Studies Research Group, we are delighted to invite guest blog entries and articles from fellow Queer Fears Network and Gender Studies Research Group members throughout the month of October.

We are also pleased to announce this as part of a series of Halloween/Gothic oriented events to re-launch the Gender Studies Research Group. This month’s rotating blog entries include pieces released on a weekly basis on Joel Schumacher’s Queer Fears looking at Flatliners and The Lost Boys; American Horror Story’s Diabolical Divas and Goddesses and Lovecraft Country’s Problematic Trans/Queer Narratives. Later in the month – we will be hosting a discussion panel from contributors to the edited collection as part of the book launch on 26th October which you can sign up for here. We will also be represented at this year’s Out For Blood Film Festival (presented exclusively online due to the pandemic) with a newly created video essay: ‘Pride and Pathology: Queer Horror and Mental Anguish’ on the 29th October.

We very much hope you enjoy the blog entries and articles throughout the month.

Happy Halloween !

This week we have:

Strange Bedfellows: Queering Sex, Death, Masculinity and the Family in Joel Schumacher’s The Lost Boys and Flatliners

written by Ben Wheeler

Do you remember any of your plans for your death?

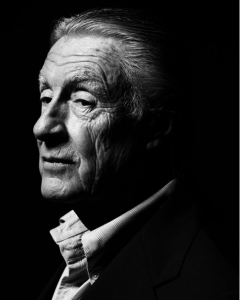

After [the negative test] I think I got wilder. What my psychiatrist said that was really fascinating was, “No, you are desperately afraid of death. It’s like swimming out further and further every night in the ocean and seeing if you can get back, and when you get home it’s like, ‘I fucked death!’”[1]

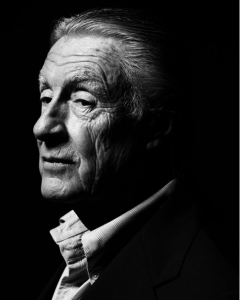

This is Joel Schumacher recalling a conversation he had circa 1983 shortly after receiving news from his doctor that he did not have AIDS. It proves a useful starting point for a discussion of queerness in two of his films made in the following years: The Lost Boys (1987) and Flatliners (1990). Although each is a generic hybrid, both can be identified as horror, and represent conflations of sex and death while subverting traditional ideas about masculinity and constructions of the family in ways central to queer theory.

These facets of Schumacher’s cinematic world recall Leo Bersani’s influential essay ‘Is the Rectum a Grave?’ –published in 1987, the year The Lost Boys was released – which addresses issues surrounding, ‘the advent of the AIDS epidemic and the birth of queer theory.’[2] The conflation, or in Bersani’s terms ‘displacement’, of sex with death (as well as the death of traditional notions of masculinity) are here seen as the result of a pervasive sense of trauma that permeated gay subcultures in the 1980s through the physiology of gay sex, and compounded by media representations of both AIDS and homosexuality at a time when, ‘the family identity produced on American television [was] more likely to include your dog than your homosexual brother or sister.’[3]

In concluding his essay Bersani suggests that:

If the rectum is the grave in which the masculine ideal (an ideal shared – differently – by men and women) of proud subjectivity is buried, then it should be celebrated for its very potential for death.[4]

I would like to suggest that in the films of Joel Schumacher – especially these two horrors – one finds a sometimes playful, sometimes painful queer aesthetic isomorphic to the ideas set out in Bersani’s essay that represents a substantial injection of queerness into the late twentieth-century Hollywood mainstream.

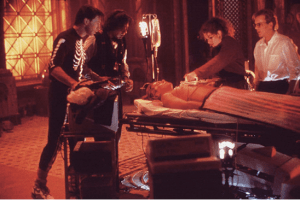

The Lost Boys

Where better to start a discussion of sex and death than a film about a gang of vampires on the hunt for new recruits? Perhaps nowhere else are these apparent binaries so confusingly muddled than in a creature who is both highly eroticised and undead, delivers pleasure and pain through a bite, and promises both death and eternal life through the exchange of bodily fluids.

As Harry Benshoff suggests in Monsters in the Closet, ‘many monster movies (and the source material they draw upon) might be understood as being “about” the eruption of some form of queer sexuality into the midst of a resolutely heterosexual milieu.’[5] The Lost Boys playfully foregrounds the homoerotic tensions between the male leads Michael (Jason Patric) and David (Kiefer Sutherland) as they battle – allegedly – for the affection of the gang’s only female member, Star (Jami Gertz).

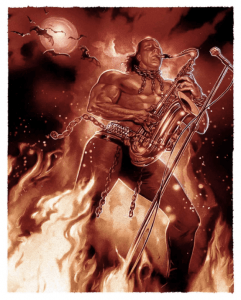

A close look at their first encounter, however, reveals something very queer indeed. Michael and Star’s first looks at one another, which signal their desire, are punctuated with shots of a sweaty, bare-chested, pumped-up male singer. The shots suggest that the female is being used to buffer or triangulate male homoerotic desires, and in just a few more scenes David and Michael are playing chicken together. Then Michael challenges David to a fight:

“Just you – just you – come on!” Making the homoeroticism of their male bonding apparent, David salaciously responds, “How far you willing to go, Michael?”[6]

As it turns out, Michael must go “all the way”. After drinking what later turns out to be David’s blood, both Michael and the Lost Boys hang onto the underside of a bridge whilst a train rolls overhead until they can no longer retain their grip and plummet into a smoky void – a scene Sutherland recalls as “a very sensual moment.”[7]

In the film’s climactic scene, Michael kills David after a prolonged tussle, with fangs and claws exposed, in what Carol Clover might refer to as ‘attacker and attacked [in] a primitive, animalistic embrace.’[8] David is finally impaled on a set of antlers in a moment that is both breathy and breath taking.

Following the subsequent penetration of the vampiric paterfamilias – Max (Edward Herrmann) – by Grandpa Emerson (Barnard Hughes), the suggestion would be that the queer sexual threat to the moral order posed by the Lost Boys had similarly been vanquished. Indeed, this had been the aim of the vampire-hunting Frog Brothers (Corey Feldman and Jamison Newlander) who tell Sam (Corey Haim):

“We’ve been aware there’s some pretty serious vampire activity in this town for some time … as a matter of fact we’re almost certain ghouls and werewolves occupy high positions at City Hall.”

This echoes what Bersani describes as the ‘charming illusion that “national gay leaders” are [politically] powerful.’[9] Moreover, the brothers’ stated mission to eliminate the local vampire group (“Kill your brother – you’ll feel better”, “Kill them all!”) taps into the ‘perverted logic of the gay-basher’[10] and recalls that, ‘the impulse to kill gays comes out as rage against gay killers deliberately spreading a deadly virus among the general public.’[11]

However, what is interesting about the world created in The Lost Boys is that it is not just the vampires who are coded as gay (they are described variously as ‘leather queens’[12] and ‘gay male pin-ups’[13]) with nominal hero Sam in particular:

coded so heavily as gay that one suspects the production designer must have had a direct pipeline into gay culture. Throughout the film, Sam wears a Mondrian-inspired bathrobe, a “Born to Shop” T-shirt, and his bedroom wall sports a sultry mid-1980s pin-up of Rob Lowe baring his belly and pouting at the camera.[14]

Even the supposedly hypermasculine Frog Brothers – whose paramilitary attire and posturing reference characters from Van Helsing to Rambo – spend most of their actual encounters with vampires screaming and clutching each other.

Moreover this is the story of two families: the Lost Boys themselves are a family, headed by Max, whose courtship of Lucy (Dianne Weist) is really about forming “One big happy family. Your boys … and mine!” The Emersons themselves are a far cry from The Brady Bunch, the family arriving in Santa Carla with Lucy fresh from a divorce and, by all accounts, a casualty of the hippie movement, finding her father growing marijuana at home, rejecting mainstream media propaganda and excited about a date with the somewhat morbid-sounding Widow Johnson.

At a time when Reagan’s America feared for the mythologised moral fabric of society in a way that had not happened since the 1960s, Schumacher was sneaking films about families steeped in the sex, drugs and rock and roll of that era in the back door, as it were.[15] As he himself has said, The Lost Boys is ‘about the fear we have of the Other – those who live outside of the mainstream.’ [16] But within its diegetic world, there is no “normal” against which to compare the vampires. Everyone in Santa Carla, regardless of age, class, or gender is – for want of a better phrase – a bit queer.

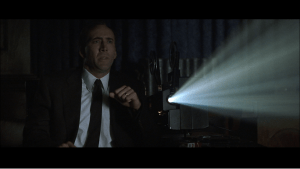

Flatliners

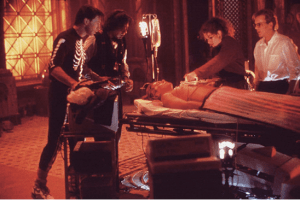

This exploration of the unknown via conflations of sex, death, pleasure and pain is again at work (and play) in Schumacher’s next excursion into the realms of the fantastic. Flatliners blends elements of science fiction and horror, and once again stars young, beautiful, up-and-coming Hollywood heart-throbs, this time as a group of medical students who set out to prove or disprove the existence of the afterlife by simulating death and then reviving each other.

The fetishisation of death is apparent from the outset. In an echo of David’s taunt in The Lost Boys (“How far you willing to go?”) it is Nelson Wright – Sutherland again – who initiates both the experiment and the idea of how “deep” each student is willing to go into the death experience as a determining factor of who will be allowed to participate.

As the film progresses however, it is revealed that the near-death experience is in fact profoundly traumatising as repressed memories, underpinned by guilt, manifest both emotionally and physically. The return of these repressed feelings threatens the subjectivity, sanity and even the lives of those who have participated.

Here once again we find echoes of Bersani’s essay, not only in the emphasis on guilt as a concomitant of both gay sex and AIDS-related death – ‘it is as if gay men’s “guilt” were the real agent of infection’[17] – but also the association of sexual acts with more than just “the exercise or loss of power … but rather a more radical disintegration and humiliation of the self.’[18]

Over the course of the film, the male protagonists who experience “death” find themselves at the receiving end of their most abusive behaviours in an escalating series of hallucinations that allow them to relive their most guilt-ridden repressed memories of accidental killing, bullying and the misogynistic videotaping of sexual infidelity.

It is as if, after assuming the position of vulnerability on the operating table – not dissimilar to the position that informs Bersani’s discussion of both straight and gay sex, that of powerlessness, of relinquished control, of being “under” – that they experience a radical shift of their perceptions of power and its operation in the world. In this position, Bersani posits, one finds the aforementioned, ‘masculine ideal (an ideal shared – differently – by men and women) of proud subjectivity’ and the potential for its annihilation, or in the case of Flatliners, its dramatic reconfiguration.

Interestingly, within this subversion of the psychodynamics of power there is an exception. Dr Rachel Mannus (Julia Roberts) blames herself for the suicide of her father. She has accepted responsibility for something that is revealed in her near-death experience to have been not her fault and beyond her control. There is then a suggestion here, in my reading of Bersani’s theory, that the shattering of male subjectivity may involve, as a corollary, female emancipation.

Afterthoughts

From the quote with which this discussion began to the idea Schumacher promulgated during the publicity trail for Flatliners that the characters “court death … and if you court death there will be consequences”[19] (said, it must be observed, with an undeniable and mischievous smirk on his face), it certainly appears that the director is aware of the prominence of the queer conflation or displacement of death with sex in his films.

In different ways and to different extents the ideas explored here inform more of Schumacher’s oeuvre as it continues into the 1990s. Falling Down (1993) suggests both the breakdown of the nuclear family as concomitant with the perceived waning of the dominance of straight, white masculinity in American society.[20] Batman Forever (1995) and Batman and Robin (1997) have now passed into legend as exploring and exploding the campy, homoerotic subtext of the mythology of the Dark Knight to the extent that the franchise had to be rigorously “de-queered” in the Christopher Nolan reboot.[21]

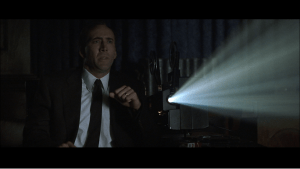

Most interestingly – for the purposes of this article at least – Schumacher’s 1999 film 8MM sees a return with a literal vengeance to the themes I have explored in The Lost Boys and Flatliners. It centres on a private detective who accepts the charge of proving that a snuff film discovered by a grieving widow amongst her husband’s possessions is a fake. When he cannot do this he resolves, agonisingly, to punish the 8mm film’s creators (and in the process himself) in escalating acts of moral masochism and violent retribution in the seedy underbelly of California’s porn and S&M scene.

To be continued…

Ben Wheeler is an independent researcher and is currently based in Fiji.

ENDNOTES and REFERENCES:

[1] ‘In Conversation: Joel Schumacher’ Vulture https://www.vulture.com/2020/06/joel-schumacher-in-conversation.html

[2] Bersani, Is the Rectum a Grave? And Other Essays, Preface

[3] Bersani, ‘Is the Rectum a Grave?’ p9

[4] Bersani, ‘Is the Rectum a Grave?’ p29

[5] Benshoff, Monsters in the Closet, p4

[6] Benshoff, Monsters in the Closet, p253

[7] ‘How The Lost Boys Made Vampires Sexy’ https://www.gamesradar.com/lost-boys-sexy-vampires-buffy-twilight/

[8] Clover, Men, Women and Chain Saws, p32

[9] Bersani, ‘Is the Rectum a Grave?’ p17

[10] Benshoff, Monsters in the Closet, p254

[11] Bersani, ‘Is the Rectum a Grave?’ p27

[12] Kalidi, ’10 Reasons The Lost Boys is the Gayest Vampire Movie, http://weareflagrant.com/10-reasons-why-the-lost-boys-is-the-gayest-vampire-movie/

[13] Benshoff, Monsters in the Closet, p253

[14] Benshoff, Monsters in the Closet, p253

[15] This socio-political connection is even indexed in the use of The Doors’ 1967 paean to difference People are Strange, but updated by 1980s group Echo & The Bunnymen

[16] ‘How The Lost Boys Made Vampires Sexy’ https://www.gamesradar.com/lost-boys-sexy-vampires-buffy-twilight/

[17] Bersani, ‘Is the Rectum a Grave?’ p16

[18] Bersani, ‘Is the Rectum a Grave?’ p23

[19] ‘Director Joel Schumacher discusses his film Flatliners in 1990’

https://www.today.com/video/director-joel-schumacher-discusses-his-film-flatliners-in-1990-85791301701

[20] See Clover, ‘Falling Down and the Rise of the Average White Male’

[21] See Winstead, ‘“As a symbol I can be incorruptible”: How Christopher Nolan De-Queered The Batman of Joel Schumacher’