John Herdman reflects on the social and political currents surging through Scottish magazines in the 1960s and 70s.

This blog is a companion to our podcast interview with John Herdman.

I became a Scottish nationalist while an undergraduate at Cambridge from 1960-63. I can identify three strands in this conversion: firstly the discovery that I had a different kind of cultural identity from my new friends and acquaintances; secondly, my enthusiasm for Irish literature (particularly Yeats, Joyce and Beckett), and the sense that this felt much closer to me than did English literature; finally my discovery (initially in an anthology edited by Moray McLaren, The Wisdom of the Scots) of the poetry and ideas of Hugh MacDiarmid, of which I had been wholly ignorant. Between 1963 and 1966 I was variously in Edinburgh, Cambridge and Europe, but very much in touch with the cultural developments that were taking place in Scotland in those years: Jim Haynes’s Paperback Bookshop, of which I was a habitué, the Traverse Theatre Club which was a huge source of stimulation, and the International Writers’ Conference of August 1962 and Drama Conference the following year.

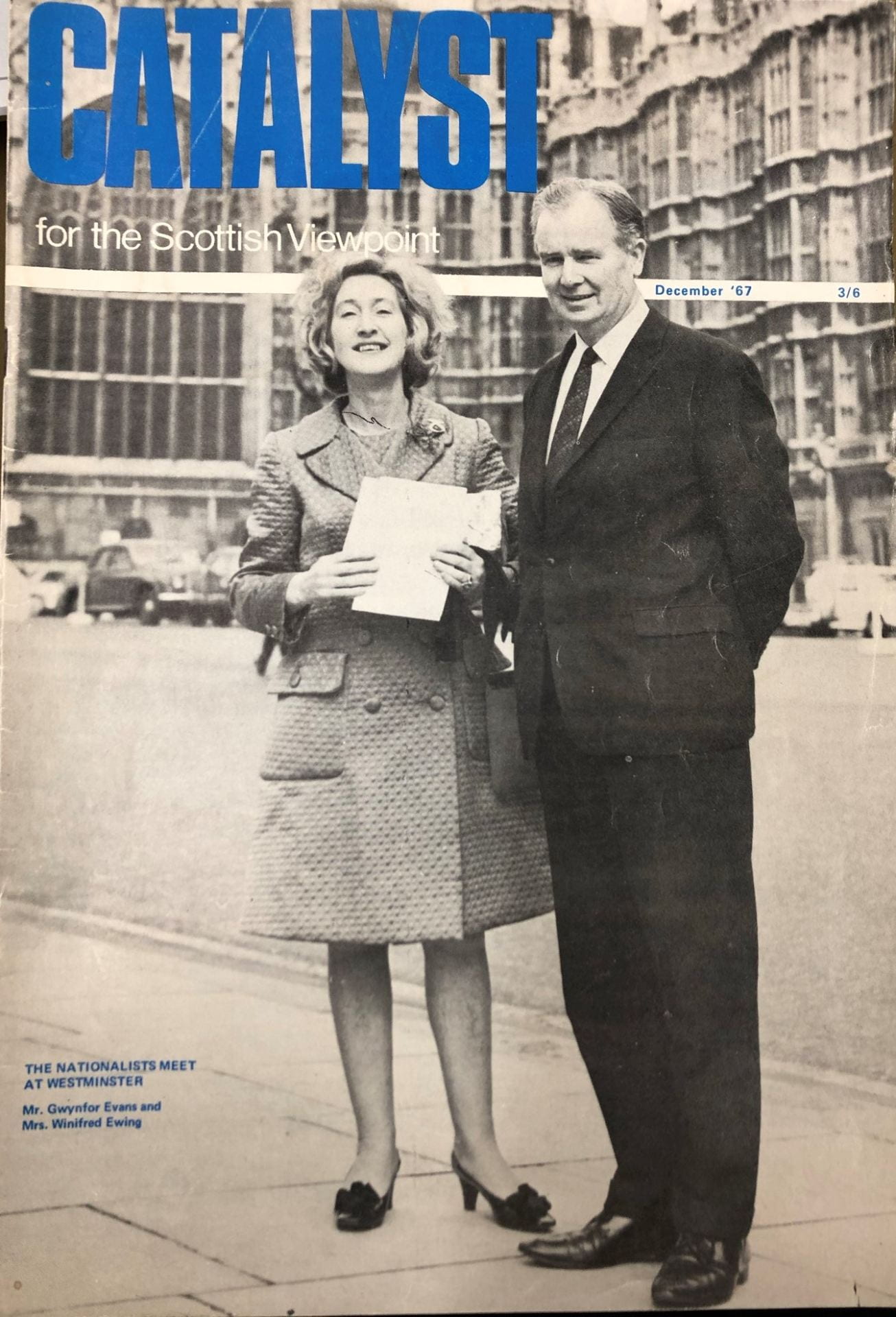

During 1966-67 I was a research student at Cambridge studying James Hogg. When I finally returned to Edinburgh in 1967 it was to a consciousness that there was a new element of life in the city, a cosmopolitanism and an innovative spirit in the arts which stood over against the very traditional middle-class world in which I had grown up, and that this was making for a far more complex interaction of different cultural and political forces than had existed hitherto. It was against this background that Winifred Ewing’s by-election victory for the SNP at Hamilton in November 1967 brought about a change in the political and cultural face of Scotland that was to prove permanent. It meant that an aspiration which had seemed little more than an unattainable pipe-dream began suddenly to appear a realistically possible, if still very distant, political goal. It was a heady time; all at once every other person in the street seemed to be sporting an SNP badge. There was of course a substantial element of fashion in this. Personally, I became quickly disillusioned by the philistinism and tokenism of the SNP’s cultural policies, and with its excessive preoccupation with economics to the detriment of the issues that seemed most important to me; and I had hoped for a far more determined and militant follow-up.

It was in 1968-9 that I began to write for Scottish periodicals, first for Catalyst of which I was briefly editor in 1970, then for Akros. Within the next few years I contributed to most of the magazines then publishing. They provided an enviable critical culture in which the new creative work of Scottish writers both established and emerging was received and evaluated, and ensured that new work was noticed even when ignored by the press; although newspapers too were mostly assiduous in reviewing new Scottish work. (To give a personal example, my second novel, Pagan’s Pilgrimage, received nine reviews when it appeared in 1978.) Another very important function performed by the literary journals lay in providing work and activity – reviewing and the writing of longer critical articles on contemporary Scottish writing – for writers like myself. Financial rewards may have been small, but one felt part of a literary community, and the interactions involved gave rise to many friendships and the formation of wide circles of acquaintance. Though some of the connections made may have been confrontational, the magazines as scenes of literary and cultural debate were educational. Writers quickly came to learn who represented what sets of attitudes, but over the literary community as a whole there was a sense of overall cohesiveness which made the atmosphere very different from that of the more fragmented and perhaps individualistic scene of today. Also very important were the book publishing arms of several of the magazines which gave many young writers, including myself, the chance of publication which they were unlikely to receive from the large metropolitan publishers.

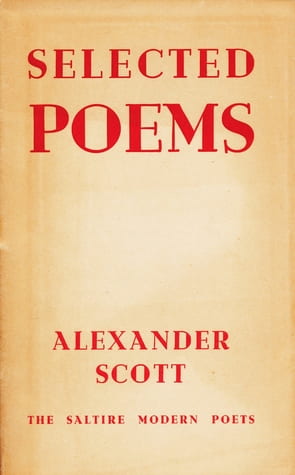

The most obvious ideological division among poets was that between the advocates of Scots or Lallans, and the considerably larger number, never really constituting a coherent grouping, who for one reason or another chose to write in English. This debate originated in Hugh MacDiarmid’s espousal of the Scots tongue (although most of his own later work was in English), and the association of that choice with Scottish patriotism and nationalism. Within this group, however, there were infinite gradations and inflections, both in ideas relating to what sort of Scots was employed (a “synthetic” diction combining contemporary speech with a drawing on the heritage of the makars, a stronger emphasis on the contemporary, or simply “the Scots I hear in my head” as Duncan Glen, the editor of Akros, used to say); and in how all this correlated with an overt political stance. Among the “second generation” Scottish Renaissance poets the most militantly patriotic was probably Tom Scott, followed by Sydney Goodsir Smith and Alexander Scott (the two Scotts hated each other). Robert Garioch was less overtly political; Duncan Glen was younger than this group, militant culturally but tended not to make political statements.

Of course the linguistic question was all-important for Gaels: Sorley MacLean, though never describing himself as a nationalist, supported independence and was never shy of identifying himself as both a Scottish and a Gaelic patriot; Derick Thomson, much more the official face of Gaeldom, was a straightforward SNP man. Almost all of these writers were also socialists, but here again the differences of nuance were considerable. The “Renaissance” men, often taking a John Maclean line, were socialists of a quite different kind from the younger writers who gravitated around Scottish International, the new journal launched in 1968 with very substantial backing from the Scottish Arts Council, and who were much more oriented towards an “internationalist” outlook. The principal of these was Bob Tait, SI’s managing editor who was supported on the editorial board by Edwin Morgan and (as a mere makeweight in MacDiarmid’s view) Robert Garioch. MacDiarmid and Tom Scott regarded all this grouping as toadies of the establishment, and despised the cultural interests of at least some of them – the Beat poets, Burroughs and Alexander Trocchi, concrete poetry. (MacDiarmid and his followers would have regarded themselves as definitely internationalist in outlook, but not as cosmopolitan – a very significant distinction.) Meanwhile Norman MacCaig, the leading Scottish poet writing in English and MacDiarmid’s close friend, remained politically au dessus de la mêlée; while Robin Fulton, a long-time editor of Lines Review around the middle of this period, was notably hostile to nationalism, both political and cultural, without showing any other overt political leaning. There can be little doubt that the main impetus for the remarkable explosion of magazine activity in these years was the slow awakening of national consciousness in Scotland exemplified by the influence of Hugh MacDiarmid but mediated by a host of less readily definable historical and social developments.

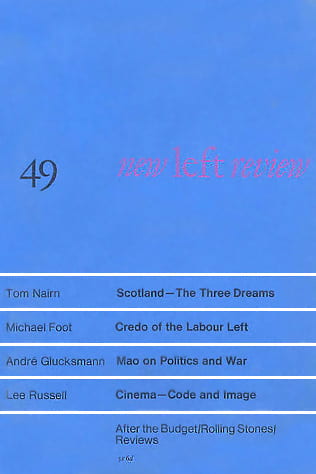

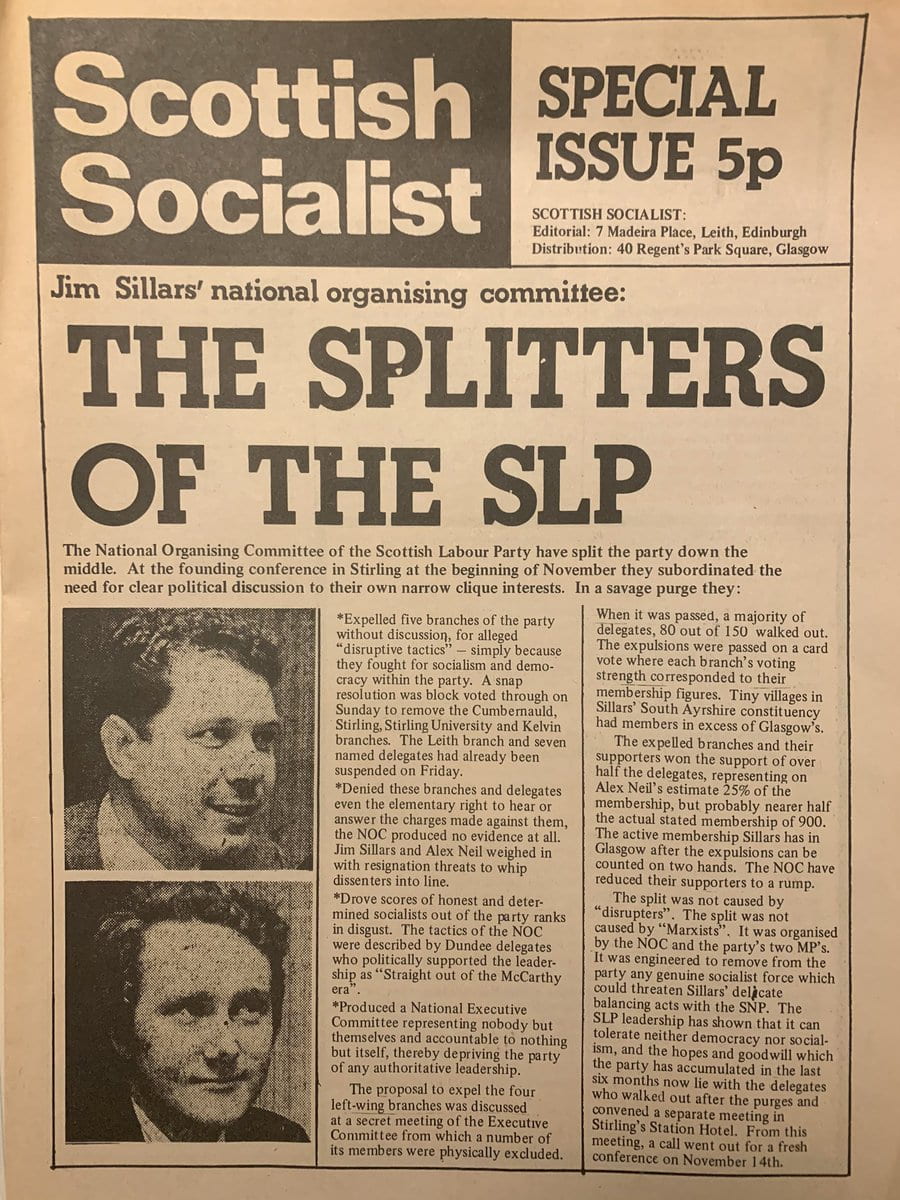

On the question of all this activity bringing together nationalists and socialists, in the shorter term it may have reinforced differences, but over time the effect was different. The approach of Scottish International was broadly sociological; the stance it took on Scottish issues could be described as anti-centralist, perhaps devolutionist from a socialist perspective. Many of those who took this line and started off very distrustful of “bourgeois nationalism” and identity politics in general, became in the course of the 1970s increasingly conscious of the national dimension, and progressively gravitated towards a more pro-independence position. Bob Tait himself was to join Jim Sillars’s breakaway Scottish Labour Party, and eventually the SNP. The political and social commentary in SI, especially after it changed from quarterly to monthly publication, probably encouraged the emergence of the incisive and influential political commentators on Scottish society such as Tom Nairn and Neal Ascherson who began to be prominent towards the end of the ‘70s. A lasting impression of these years is the sheer profusion of cultural activities and events which they spawned – poetry festivals, innumerable readings, book launches, film showings, theatrical events and “happenings” of all kinds – and the remarkable phenomenon of the folk music scene, which tended to bring together artists of many different shades and temperaments and of varied political and other persuasions.

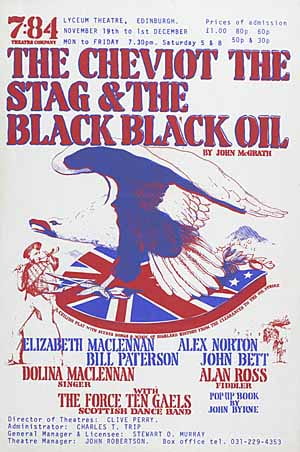

Bob Tait, as editor of SI, planned the “What Kind of Scotland?” Conference of April 1973 with the controlling idea of showing that it was insufficient to argue for independence for Scotland without a clear idea of what kind of society was envisaged for that independent entity. He invited two nationalists (Stephen Maxwell and myself) to join the organising committee. The conference was successful, I think, particularly in encouraging the development of the movement of informed and committed political and social commentary alluded to above. But the undoubted and quite unexpected highlight proved to be the originally unplanned rehearsed reading of John McGrath’s play The Cheviot, the Stag and the Black, Black Oil – the first airing by the 7:84 Company of the explosive work that was to take audiences throughout Scotland by storm on its first tour, which immediately followed this occasion. This play brought into focus the whole question of the degree to which socialist and nationalist objectives, and interpretations of history, might differ or coincide. The 7:84 Company insisted that its message was entirely socialist, yet again and again its audiences interpreted the story it had to tell as a nationalist object lesson. This was a tension which would have a long history and would not easily disappear.

The pub life of the Edinburgh cultural world of these years had two main foci – the Rose Street pubs where the older poets of the “second wave” Renaissance were accustomed to meet, drink, laugh and argue: Milne’s Bar, the Abbotsford and Paddy’s Bar were the most frequented. The atmosphere around the bards could be jovial but it could also be argumentative, given to “flyting”, even at odd moments violent. This was against the background of a normal Edinburgh pub atmosphere in which people from widely differing social backgrounds mingled easily. The second focus was Sandy Bell’s Bar in Forrest Road, which had a clientele of which the core consisted of “folkies” (it was and still is the main Edinburgh folk music pub) and students, at that time predominantly medical students, and was favoured by intellectuals of all sorts, by poets, writers and artists. As it is a very small, narrow pub (and in those days very smoky) the boisterous crowding was considerable and very much part of its charm. One of its many fixtures was the great folklorist Hamish Henderson, who united socialism and nationalism in his extraordinary person.

A story told me by a friend who often visits Turkey says a lot about the Sandy Bell’s of those days. In Istanbul a young Turk was showing an assembled company photos of his visit to Edinburgh. Coming to one photo he said, “And this is the School of Scottish Studies.” “No, no,” said my friend, “that’s Sandy Bell’s Bar.” “No, no, School of Scottish Studies!” He couldn’t be convinced otherwise; and it’s perhaps not difficult to imagine how the confusion might have arisen. This was still to a large extent a man’s world, but women writers were becoming rather more visible by the end of the ‘70s. Among the female poets who were emerging in those years the most prominent was Liz Lochhead; others of note were Val Simmonds, later Gillies; Tessa Ransford, later founder of the Scottish Poetry Library; and Catherine Lucy Czerkawska. An outstanding editor was Joy Hendry, who after co-editing Chapman for some years with her then husband Walter Perrie, continued for very many years as an enormously hard-working sole editor. The most memorable and protracted debate which took place in the magazines of those years was the one which arose from the cleverly provocative attack on nationalist writers by the poet Alan Jackson in the pages of Lines Review in 1971. In the special supplement which followed, some of the writers attacked, and several others, had a chance to air and express their personal positions in a way which allowed them to dissent from being assimilated to any stereotyped view.

A story told me by a friend who often visits Turkey says a lot about the Sandy Bell’s of those days. In Istanbul a young Turk was showing an assembled company photos of his visit to Edinburgh. Coming to one photo he said, “And this is the School of Scottish Studies.” “No, no,” said my friend, “that’s Sandy Bell’s Bar.” “No, no, School of Scottish Studies!” He couldn’t be convinced otherwise; and it’s perhaps not difficult to imagine how the confusion might have arisen. This was still to a large extent a man’s world, but women writers were becoming rather more visible by the end of the ‘70s. Among the female poets who were emerging in those years the most prominent was Liz Lochhead; others of note were Val Simmonds, later Gillies; Tessa Ransford, later founder of the Scottish Poetry Library; and Catherine Lucy Czerkawska. An outstanding editor was Joy Hendry, who after co-editing Chapman for some years with her then husband Walter Perrie, continued for very many years as an enormously hard-working sole editor. The most memorable and protracted debate which took place in the magazines of those years was the one which arose from the cleverly provocative attack on nationalist writers by the poet Alan Jackson in the pages of Lines Review in 1971. In the special supplement which followed, some of the writers attacked, and several others, had a chance to air and express their personal positions in a way which allowed them to dissent from being assimilated to any stereotyped view.

As F.R. Leavis used to say, “Minorities can be disproportionately influential”, and this is doubtless true of those who wrote in these Scottish magazines in the years under discussion, though the reach of their impact is impossible to estimate, far less quantify. What is certain is that these publications performed a most valuable cultural function in the discussion of Scottish writing and politics at a time of great intellectual ferment, and that they contain still great resources for the study of twentieth century Scottish writing within its wider context.

John Herdman was born in Edinburgh, and educated there and at Magdalene College, Cambridge, where he read English and later took his PhD. He is a novelist, short story writer and literary critic, whose most recent story collection is My Wife’s Lovers (2007). As a critic he has published a study of Bob Dylan’s lyrics, Voice Without Restraint (1982), and The Double in Nineteenth-Century Fiction (1990), as well as much work on modern Scottish literature. Another Country (2013) is a memoir of literary-political life in Scotland in the 1960s and 1970s.