Rory Scothorne explores a path-breaking radical magazine of the 1970s, a Highland ‘vehicle for a revolutionary Scottish Gramscianism’

“Vietnam: Victory to the NLF”, proclaimed the second issue of Calgacus magazine, published in Summer 1975 shortly after the Viet Cong’s capture of Saigon. Page 48 was surprisingly low billing, however, for the long-awaited conclusion of the Vietnamese liberation struggle that had animated and helped to transform radical politics across the western world. Calgacus reflected that transformation, albeit in a uniquely Scottish form.

The magazine’s editor, helming a rather prestigious editorial committee, was the 29-year-old teacher and journalist Ray Burnett, who produced the three issues of Calgacus – two in 1975, one in early 1976 – from his home in Wester Ross before the magazine fizzled out of existence. Burnett had spent the late 1960s on a Forrest Gump-like tour of radical flashpoints. Not only had been on the frontline of the famous anti-Vietnam War demonstration in London in March 1968, when 246 protesters were arrested amidst clashes with police, he was also present at the Battle of the Bogside in Derry the following year, when fighting between unionist marchers and predominantly Catholic locals led to days of police violence followed by British Army intervention.

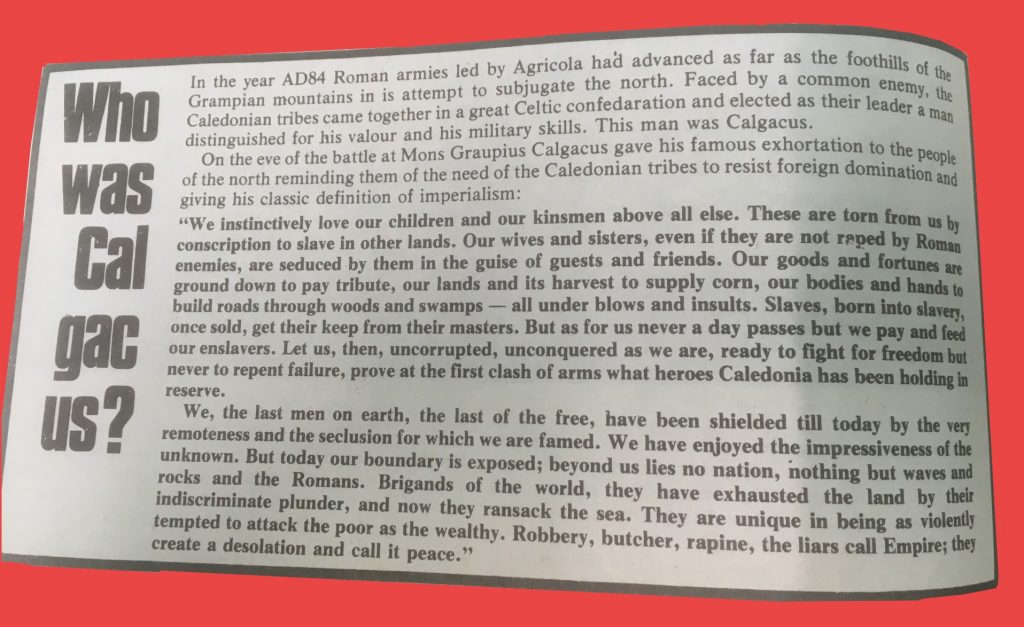

These were battles between great powers and plucky underdogs, and Calgacus sought to articulate a distinctive Scottish radicalism within that global tradition of resistance. It was named after the first-century Caledonian chieftain who challenged Roman invasion, to whom Tacitus attributed the famous anti-imperialist speech that was quoted in each issue of the magazine:

We, the last men on earth, the last of the free, have been shielded till today by the very remoteness and seclusion for which we are famed. We have enjoyed the impressiveness of the unknown. But today our boundary is exposed; beyond us lies no nation, nothing but waves and rocks and the Romans. Brigands of the world, they have exhausted the land by their indiscriminate plunder, and now they ransack the sea. They are unique in being as violently tempted to attack the poor as the wealth. Robbery, butcher, rapine, the liars call Empire; they create a desolation and call it peace.

Such overtly left-nationalist symbolism was intended as a provocation, reflecting Burnett’s growing frustration with what he saw as the British left’s neglect of Scottish questions. Until the early 1970s, Burnett had been an active member of the International Socialists, a precursor of the Socialist Workers’ Party. British Trotskyism was highly London-centric, and while the SNP’s rise since the late 1960s had not been lost on Trotskyist intellectuals, their responses had largely dismissed the idea that this reflected a distinctive Scottish polity worth engaging with more positively.

Burnett disagreed. “The present crisis of capitalism,” he wrote in Calgacus’ first editorial, “is neither a particularly Scottish problem nor even particularly British: it is an economic trough of global dimensions.” However, “when such a universal phenomena is related to a specific reality then that juncture is in our case an economic, political and social prism both definable and recognisable as Scotland.” The magazine’s identity was thus not just self-consciously Scottish but defiantly so: “Calgacus is guilty of that most heinous sin in the catalogues of the British Left – we admit that Scotland exists.”

Burnett had laid out this position in more detail three years earlier, in an essay for Scottish International titled ‘Scotland and Antonio Gramsci’. Alongside a panoramic critique of what he saw as the prevailing left-wing approaches to the national question in Scotland, Burnett offered his own pioneering analysis, drawing on Gramsci’s distinction between “political” and “civil” society (and later quoted prominently in Tom Nairn’s 1977 Break-up of Britain): “While we have a homogenous British state,” he argued, “the organisations and institutions in civil society which comprise its bulwarks and defences have an azoic complexity, the most significant feature of which for us is that civil society in Scotland is fundamentally different from that in England.” Thus Scottish culture and its distinctive institutions mattered profoundly to socialists seeking to counter bourgeois ideology: “Much of our shared ‘British’ ideology as it manifests itself in Scotland, draws its vigour and strength from a specifically Scottish heritage of myths, prejudices and illusions.”

Alongside this need for a more thorough socialist critique of Scottish identity, Burnett also emphasised the importance of defending its liberating and collectivist features. “The left must uphold and expound the merits of past achievements and the richness of our inheritance,” he wrote: “we must cherish the diverse contributions of the flowering Makar and the rantin’ ploughboy, the radical weaver, the passionate Gael, and the rovin’ tinker. If we do not, then what price ‘the revolution’?”

This position also reflected the influence of the folklorist, poet and Communist fellow-traveller Hamish Henderson, whose 1940s translations of Gramsci’s prison letters were first published in the New Edinburgh Review between 1973 and 1974. Henderson was central to Calgacus’ conceptualisation, though ultimately not formative. In an interview, Burnett told me that Henderson suggested the name Mac-Talla (after a successful Gaelic periodical based in Nova Scotia between 1892 and 1904), which Burnett rejected due to the limited Gaelic audience. Henderson also proposed Christopher Grieve (aka Hugh MacDiarmid) for the editorial board, but Burnett rejected this, too – MacDiarmid had alienated much of the Scottish new left with his support for the Soviet repression of Hungary and Czechoslovakia in 1956 and 1968 respectively. Calgacus was thus intended as a vehicle for a revolutionary Scottish Gramscianism, staking a socialist claim on Scotland’s “national-popular” that placed the rights – and radicalism – of minority identities at its heart.

For this reason as well as its location, Calgacus stood out amongst the largely Edinburgh-centric national periodicals of the 1970s due to its focus on the Highlands and Islands. Burnett had previously written for the West Highland Free Press based at Kyleakin on Skye, which had been established in 1972 by a group of Dundee University students, and the newspaper’s publishing arm also produced Calgacus. This ensured a distinctive interpenetration of regional and national questions, and issue 2 foregrounded the Gaelic slogan Tir is Teanga (“land and language”) on its front cover.

This was accompanied by articles about the land reformer and newspaper editor John Murdoch and excerpts from his work; maps of land ownership on the Argyll Islands; an essay by the Gaelic scholar John MacInnes on Sorley Maclean’s Hallaig, and an essay by the German poet Hans Magnus Enzensberger on “A Theory of Tourism”. Other issues also paid close attention to the region: Issue 1 featured an essay from Sorley Maclean on Gaelic poetry as well as detailed coverage of the North Sea Oil industry and its workforce, while Issue 3 included an article by James Hunter on nineteenth century land struggles and an essay on the land question by the SNP activist Frank Thompson.

While there was a clear rural and ethnic minoritarianism to much of this coverage, Calgacus also reflected the politics of a largely Anglophone, urban and university-educated intelligentsia that was looking to Scottish nationalism as a source of authenticity and self-legitimation. On the opposite page from “Victory to the Viet Cong” was an enthusiastic review of the Red Paper on Scotland, a major mid-70s statement of self-confidence from Scotland’s up-and-coming left intelligentsia edited by Gordon Brown in Edinburgh. The vague, radical-reformist and cerebral constitutional politics of the Red Paper – clearly pro-devolution, but also toying with independence in some places – jarred with another item on the same page: a folksy, populist protest lyric in favour of Scottish independence and opposed to the European Economic Community. Burnett’s own position, however, was closer to the politics of Tom Nairn and Scottish International’s editor Bob Tait, who pioneered the ‘Independence in Europe’ argument in the 1970s that would eventually be adopted by the once-Eurosceptic SNP. Calgacus’ nationalism was aware of its own potential pitfalls, pitching a cosmopolitan, outward-facing vision of cultural and political revival against the insular, homogenising state-nationalism of the UK.

Calgacus’s distinctive vision of cosmopolitan nationalism conceived of European minority-nationalism as a general rather than uniquely Scottish phenomenon, and a fundamental rather than marginal question for socialists. The composition of the (advisory) editorial board was itself a statement of intent, with a geographical spread significant enough to ensure that it never actually met. Alongside Burnett and Hamish Henderson were Tom Nairn and the Red Clydeside veteran Harry McShane; these Scots were augmented by Ned Thomas from Wales and Brian Trench from Ireland, key figures in Planet and Hibernia respectively – both vital, ground-breaking magazines in their own nations. They were joined by the Mersey-born Irish Catholic John McGrath, the author of The Cheviot, The Stag and the Black, Black Oil, on which Burnett had worked as a researcher.

The magazine’s content expanded this cosmopolitanism beyond Britain and Ireland, countering the left’s sceptical vision of a corporate, capitalist Europe with a distinctive vision of “Europe’s forgotten minorities”. This was focused not just on “the Europe of the Celtic periphery” but also “the Europe of Occitania, Galicia, Friesland, the Basques, Catalonia, Corsica, and a myriad of linguistic minorities,” reproducing translations of left-wing minority-nationalist literature from across the continent. This was justified by a particularly cultural – we might even say ethnic – idea of socialism, focused on “the salvation of humanity, the celebration of man’s achievement’s, not the annihilation of his rich diversity [italics added]”. Calgacus’s socialist, cosmopolitan nationalism can thus be understood as an attempt to redeem the idea of Europe, as a “carrying stream” of myriad precious and intertwined traditions, from the homogenising pressures of capitalist modernisation. This could be stretched to especially controversial lengths: in its third and final issue, Calgacus published Tom Nairn’s essay – later updated for The Break-up of Britain – arguing that the Irish question could be resolved by an independent Ulster.

By 1976, financial problems at the West Highland Free Press exacerbated tensions between Burnett and the WHFP’s fiercely anti-nationalist editor Brian Wilson, leading to the magazine’s demise. Calgacus was unable to find an alternative to WHFP’s already fragile access to both production and Scotland’s fraught apparatus of print-media distribution, and bad-tempered disputes on the letters pages of other magazines ensued. A fourth issue had been promised on “the place of women in Scottish society”, and its absence only amplifies the silence of women in the pages of Scottish political and cultural magazines during this period. Calgacus’ business manager Catherine MacFarlane, who married Burnett in 1967, was the sole woman involved in the magazine’s production.

Reflecting on a decade of the “revolutionary left in Scotland” in 1978, the Trotskyist intellectual Neil Williamson – who died tragically young in a car accident that year – remembered Calgacus as “almost an object lesson in irrelevance.” Any clear political impact is undoubtedly hard to find in the subsequent decades: the devolutionary form of Scottish nationalism which prevailed was far more reformist and institutionalised, deploying the majoritarian ethnic symbolism of twentieth-century Clydeside far more than the Celticist minoritarianism of Tir is Teanga. Yet class was also a vital part of Calgacus’ politics, reflecting the “land and labour” combination advocated by the Irish revolutionary James Connolly – a profound influence on Burnett, who grew up in the same Edinburgh Cowgate community as Connolly had.

While Calgacus tended to overstate – as many have – the revolutionary potential of ‘Red Clydeside’, many of Burnett’s political instincts have been vindicated, albeit without much political success to show for it. SNP activists like Frank Thompson and Rob Gibson were welcome in Calgacus’ pages, despite widespread left scepticism towards the party at the time, and this openness became common sense with the rise of the ‘79 Group. The magazine’s effort to generate a radical, multinational vision of Europe, resistant to the homogenising pressures of the EEC, is now sorely lacking from Scottish politics after Brexit.

Most importantly, Calgacus’ explicit effort to generate a “Scottish left” out of the implicitly British or de-nationalised “left in Scotland” (which was Williamson’s formulation) outlined a collective project that would animate the Scottish intelligentsia for the subsequent two decades. Just six years after Calgacus finished, the editorial collective of the left-nationalist magazine Crann-Tàra would repeat Burnett’s decision to dismiss a Gaelic title in favour of a more popular one, renaming themselves Radical Scotland to attract a broader, less fundamentalist audience.

Though it was short-lived, Calgacus was an inventive attempt to reformulate Scottish radicalism for a political world that had been transformed by the rise of the SNP. The magazine’s chosen priorities and themes can be traced through political projects from Jim Sillars’ “breakaway” Scottish Labour Party (of which Burnett was a member) to the Scottish Socialist Party, the Radical Independence Campaign and the Scottish Greens, as well as media outlets like Bella Caledonia.

Rory Scothorne is a writer and historian who recently completed a PhD on ‘The Radical Left and the Scottish Nation Print-Cultures of Left-Wing Nationalism, 1967-1983’. He writes on Scottish and British politics for the New Statesman.