James Campbell recalls the perennial re-making of New Edinburgh Review

The post of editor of the New Edinburgh Review was advertised in the weekly university newspaper, The Student, in May 1978. The NER, a journal of quarterly publication, could be seen as The Student in grown-up form. The two publications shared the offices of Edinburgh University Student Publications Board (EUSPB) but lived separate lives. Although published and administered by EUSPB, the NER occupied a territory bounded on the one side by the London weeklies, such as the New Statesman, and on the other by quasi-academic periodicals like Critical Quarterly, with an outlook on sociology and what would soon be known as cultural studies. Contributors to the early issues wrote for little or no payment. Some were based in university departments and the specialist coloration they lent to the journal was apt to depend on who was in charge of the NER at the time.

The editor of the NER for the past several numbers had been Owen Dudley Edwards, an unavoidable presence around the campus, possessed of formidable erudition and a fluent way of expounding it in an Irish accent. Although a tenured employee of the History department, he was an influential member of the Student Publications Board, which did not insist that its members be students.

NER was based at No 1 Buccleuch Place, just along the street from No 18, where the original Edinburgh Review had been founded in 1802 by Francis Jeffrey, Sydney Smith, Francis Horner and Henry Brougham. In the first quarter of the nineteenth century, it was the most influential journal of literary criticism, political opinion, philosophy and scientific discovery in Britain. Street association apart, however, the inferred relationship between the two magazines was dubious, to say the least. Nos 1 and 18 Buccleuch Place were separated by 150 yards of granite cobblestones and 150 years of intellectual thought. Jeffrey’s Edinburgh Review was in part the inspiration for Byron’s satirical poem “English Bards and Scotch Reviewers”, and the most severe of those disdained and feared reviewers was Jeffrey himself, at whose hands Byron had lately suffered. Jeffrey retired in 1829.

The New Edinburgh Review first appeared 140 years later, in February 1969, and settled into quarterly publication. The editor was David Cubitt. For the third issue, November 1969, readers paid two shillings, with an apology for the rise from one and sixpence for the previous issue. A post-graduate student at the university, Cubitt was unable to resist the editor’s perennial temptation to print a few of his own poems. The November 1969 editorial made a reasonable plea for good, clear style: “Scottish writers sometimes betray a tendency to look more at themselves writing Scottishly than at themselves writing properly, and decline into a species of high-class provincial tartanry.” Twenty or more years on, that “properly”, opposed as it is to “Scottishly”, would curdle any attempt at reasonable debate.

The editorship changed so frequently that the calendar year bridging November 1969 and November 1970 saw three: Cubitt, Julian Pollock and Brian Torode, not to mention an editorial consultant, two editorial advisors, a poetry editor, an editorial board of seven, and a design team of three. The main drawback to this fast-changing cast and catalogue of contents was that the average reader had no idea what the magazine stood for. But by 1975 the NER had taken a stance, and it was nothing if not determined. The sitting editor, C.K. Maisels, had few reservations about presenting himself as a political extremist who had got his hands on a ream of paper, a printer and a bunch of useful idiots.

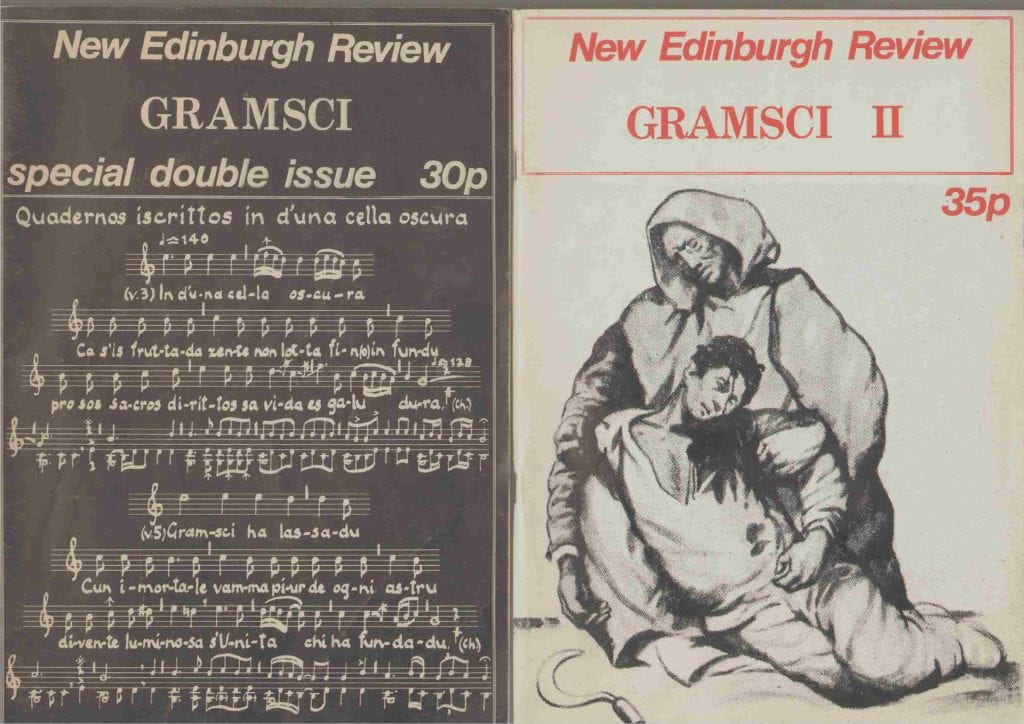

In his “Working Class Consciousness and Culture” issue, which by deduction we can identify as the last of 1974 (Maisels did away with issue numbers, dates, detailed tables of contents and contributor information, as if holdovers from a decadent era), he printed the lyrics to four songs composed by himself, complete with sheet music. “Meunier” is addressed to the Belgian sculptor Constantin Meunier, whose bronze statuette, “Woodcutter”, illustrated one of the songs:

True worker Constantin, my comrade in arms

you have shown us the workers just as they are

and you’ve looked right into them and better by far

you have seen in their minds just what could be . . . .

No art for pure art’s sake in factory and mine . . .

art for the workers is what art’s for.

In applying for the editorship, I wrote a short outline of my aims, should I be appointed. My membership of EUSPB, 1976-78, had hardly been illustrious, but it had given me familiarity with the inside of 1 Buccleuch Place, including the table at which I would be interviewed, and with some of the people who would be asking the questions. My slim literary portfolio, consisting largely of reviews of art exhibitions for The Student and my profile of Alexander Trocchi for Glasgow University Magazine (GUM), had recently been abetted by a first-person “casual” published in the New Statesman, involving modern art and an imaginary identification with Norman Mailer; by a lengthy Paris Review-style interview with the novelist John Fowles; and by some poems in decent Scottish magazines.

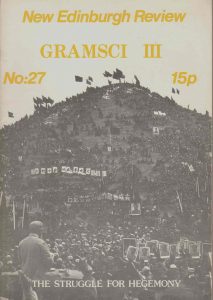

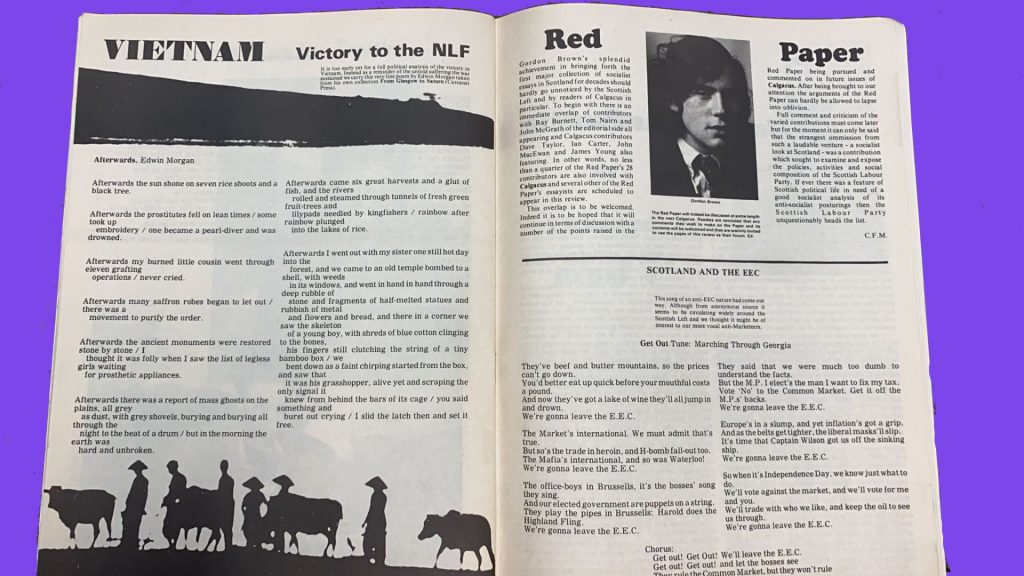

On the afternoon of June 16, I took my turn at being questioned by the panel. What would I do with the New Edinburgh Review, if successful in gaining the editorship? Well, first, ditch the thematic programme, based largely on left-wing ideology. It curtailed the general interest of the magazine; it gave the contents an off-puttingly academic character. The three issues published previous to “Working Class Consciousness and Culture” had been devoted to the letters of the Italian Marxist Antonio Gramsci, and had gained more attention than other issues of the magazine. Such concerns were beyond my purview, though worthy in themselves and clearly of interest to a niche readership. I nevertheless held to the belief that it was the wrong direction for a magazine like the New Edinburgh Review to take. Clichés such as “fallen into the clutches of” are best avoided by writers committed to “writing properly”, to borrow the phrase from that early editorial. But it was obvious to an impartial reader of back issues in bulk that since the early Cubbitt–Pollock–Torode productions – concerned largely with the social sciences but eager to give space to the arts as well – the NER had been directed by one set of ideologues after another. Wasn’t the NER sheltering under the Arts Council’s literary magazine budget?

I would introduce fiction into the NER, and bring back poetry which had been there at the start but had been dispensed of by the Maisels faction, with its banalities such as “art for the workers is what art’s for”. The magazine had at different times boasted the services of two distinguished poets as poetry editors, Robin Fulton and Robert Garioch. Some issues had one or other listed on the masthead, but no poems. Prolific writers of short stories were all around us – George Mackay Brown, Ron Butlin, Iain Crichton Smith, Alan Spence, James Kelman – and they would surely be willing to take advantage of this new outlet, once made aware of it (they were). The same went for poets. As for general features, while I intended to pay attention to Scottish affairs and to the unavoidable question of independence from Westminster, I saw no sense in the editor’s outlook meeting a portcullis at Carlisle. Scottish authors within reach of Buccleuch Place were capable of writing about a variety of subjects, were they not? If one wished to claim collegiateship with Jeffrey’s Edinburgh Review, then this was the area in which to attempt it. The interview over, I returned to my flat in Forrest Road. Before the afternoon was out, I answered a knock at the door from one of the interviewers. The job was mine.

Remuneration for the post as editor of the New Edinburgh Review came in the form of a stipend of £250 per quarterly issue, not much on which to support a restless nature. I took a job as a driver for Edinburgh Social Services, Transport Department. It was varied and enjoyable work, reasonably paid, with overtime possibilities. Specific driving duties changed from day to day, but the irregular structure meant that I was usually able to call at Buccleuch Place during a convenient interval, to see if the in-tray contained any responses to letters of solicitation, or to place others hastily written the night before in the out-tray. One day, the reply from Rome to a polite request to Muriel Spark for a short story, the next from George Mackay Brown in Orkney, in search of a story or poem. Spark: “If I have something in the way of a story in the future, I’ll remember you.” Alas, she never did have anything to spare. Mackay Brown: “I am glad you are to publish stories. There is too much lit. crit. and dissecting of books in so many of our magazines. Stories, if they’re good enough, go on for ever. I enclose ORPHEUS WITH HIS LUTE. I hope it will be suitable.” It was, and it went into my second issue (Winter 1978). Mackay Brown proved to be an unfailingly generous contributor, never omitting to append a kindly note in his attractive hand to each submission (“Have a good Christmas and a prosperous New Year”). Douglas Dunn and Iain Crichton Smith were willing supporters, too. Crichton Smith’s poems arrived on scraps of paper torn from larger sheets. Some were called just “Poem” or “Old Woman”. He also took on book reviews, in the course of writing which his shaky typewriter keys sent red letters shooting into the otherwise black type, at times below and at others above the level. Occasionally the letters of a word, or a whole line, ran down in a slope towards the right-hand margin. A flurry of Biro marks would be added later by hand. Norman MacCaig sent a sheaf of poems accompanied not by the traditional stamped addressed envelope but a handwritten note: “Here are some poems. If they are any good, print them. If not, put them in the bin.”

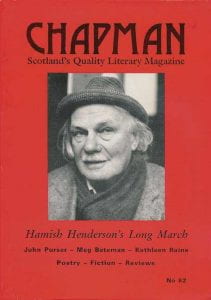

Neal Ascherson, Allan Massie, Naomi Mitchison, Edwin Morgan and Peter Porter all contributed willingly and often. The Daiches family did, too: David Daiches, his daughter Jenni Calder and her husband Angus. I received a letter from Kathleen Jamie – “I am a sixteen-year-old poet” – and published one of her earliest poems. All were Scottish writers or had a base in Scotland (Porter was a popular writer-in-residence at the university at the time). Within days of succeeding to the editorship, I wrote to Hugh MacDiarmid and received a charming reply, dated July 9, 1978. He had been in and out of hospital, was “still very ill and unlikely to improve … But while I cannot send you a poem / poems as you so kindly invite, I’ll send you something as soon as I can and have anything I think worthwhile to send. With best wishes for the NER and hopes for good results from opening its pages to poetry.” The open-handedness of these eminent figures – partly in reaction to the opening up of a new literary platform which showed signs of seriousness; partly, no doubt, in response to ingenuous youth – was a lesson in literary community that was worth cherishing and preserving.

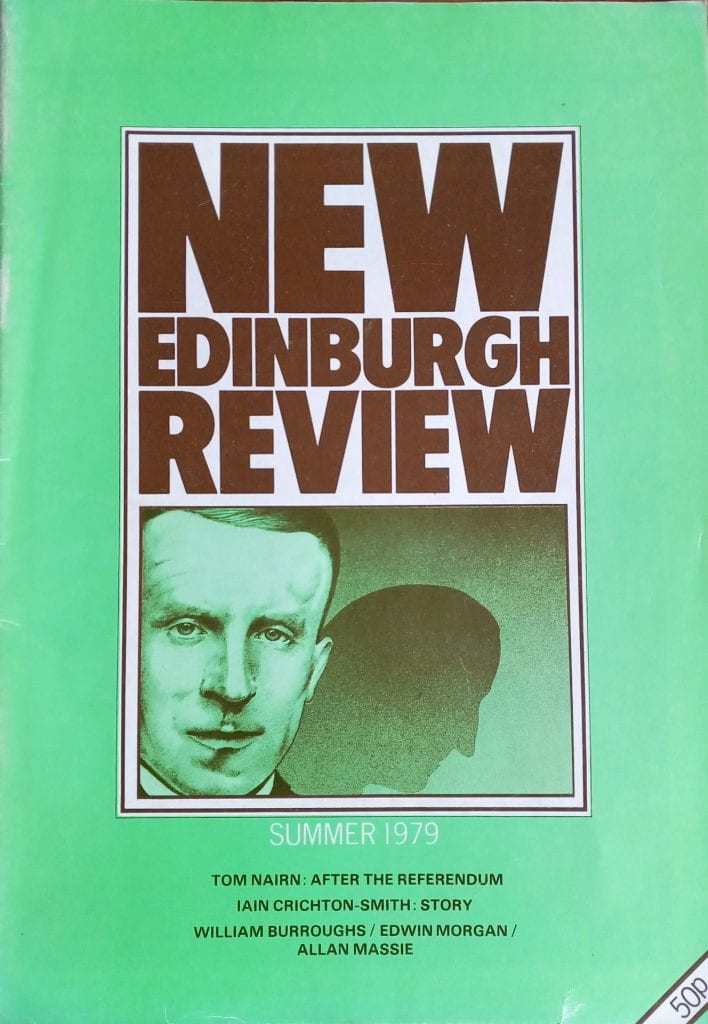

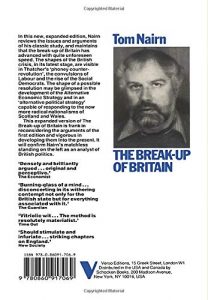

Requests for contributions were not restricted to Scottish-based writers. My magazine was to be un magasin, a shop, offering as wide a variety of goods as economically feasible to interested customers. The model I had outlined to the interview panel was something like that of the New Statesman of the time: general articles on a variety of political and cultural affairs in the front half – with an emphasis on the latter – followed by book reviews of a comparable range at the rear. Art and performance reviews were excluded only because quarterly publication would render them out of date before they appeared. One feature of the design arrangement of the NER was to have a single-page piece at the back to close the issue – a “casual”, distinct in tone from most of what had preceded it. When the Summer 1979 number was approaching a state of readiness, I still lacked something for this spot. The lead article was a post-mortem analysis of the failure of the nationalist movement to gain a sufficient majority in favour of Scottish devolution in the referendum of March that year. The author was Tom Nairn, whose sole issue as editor of the magazine, “The English Nation”, I had used while sitting before the interviewing panel as an example of precisely what I did not want for the future. But I had thrilled to Nairn’s acute and occasionally acerbic writing at other times, and was pleased when he rang up to offer “After the Referendum”. The piece was too long, as he acknowledged, and when I asked him to make it shorter, he smiled shyly and said he preferred to leave that job to me. “Editors are usually better at cutting the fat from writers’ pieces than the writers themselves.”

Nairn was a legendary figure in the left-wing intellectual sphere of the day, and I was glad to have “Tom Nairn: After the Referendum” on the cover in the wake of the event itself. From the opposite bank of the red and blue river running through the nation – a far less fashionable place to be among the country’s intelligentsia – Allan Massie wrote about John Buchan’s “other hero”, Richard Hannay, concentrating on the third of the five Hannay novels, Mr Standfast. There is a reference to red Clydeside in the story, but presented here with the distinctly un-Nairnian suggestion that “there’s a wholesome dampness about the tinder on Clydeside”. We had a short story by Iain Crichton Smith, “The Snow”, and a pair of articles about the respective southsides of Glasgow and Edinburgh. In the review section, Edwin Morgan wrote about Douglas Dunn’s prosodic virtues and sentimental vices (“‘Grudge’ is a recurring word”), and the filmmaker Murray Grigor – another one-time-only NER editor – discussed the pioneer of Scottish documentary film, John Grierson.

But I still had nothing for that back page. Then I dipped into an old bag of tricks and came up with a surprise. The piece was called “M.O.B.”, and the latest contributor to the NER was William Burroughs, the author of the novels Junkie and Naked Lunch, and co-inventor of the cut-up technique. It had been published before – but published by me, in Glasgow University Magazine, or GUM, in which I had had a hand in the early 70s, even though not a student at the university. The photostatted typescript had been given to me in London by Burroughs’s old sidekick, Alexander Trocchi, when I had interviewed him at home for GUM. The encounter had resulted in my first proper publication, and the longest piece written about Trocchi to date (GUM, February 1973). When I asked if he had something he could let me have for our magazine, he regretted having to say no. Instead, he handed over this short piece by Burroughs, with his big, confiding smile, and the simplest of instructions: “Ring Bill. Tell him I said to call. He’ll say yes.” He gave me the telephone number of Burroughs’s apartment in Duke Street St James, near Piccadilly. I did call and he did say yes. Now “M.O.B.” was making the 45-mile journey from Glasgow to Edinburgh.

I resigned from the New Edinburgh Review in 1982, having produced fifteen issues and, I’m confident in saying, having been the first editor in its twenty-three years of publication to date to try to give the job the commitment it deserved. The last of my productions, Winter 1982, contains articles by Douglas Dunn (on a reissue of Edwin Muir’s book Scott and Scotland), Edwin Morgan on the poetry of Peter Porter, Jenni Calder on setting up the Royal Scottish Museum, and Aiden Higgins (“Meeting Mr Beckett”). Among the reviewers were Stewart Conn and Gerald Mangan. Correspondence with those writers and others – Ascherson, James Baldwin, Angus Calder, Donald Campbell, Giles Gordon, Naomi Mitchison, Alan Spence, Ted Whitehead (the playwright E. A. Whitehead) – was tidied away in folders in a cupboard at Buccleuch Place. Most of the letters, naturally, were addressed to the editor. I would like to have tidied them away in a cupboard in my flat in Forrest Road but was informed that they did not belong to me. They were the property of the NER or, more broadly, EUSPB.

This was correct procedure. I nevertheless kept back some typescripts, such as James Baldwin’s of his essay “Of the Sorrow Songs”, together with a few brief notes he had sent me regarding it. The two handwritten letters from MacDiarmid I had taken home and saw little point in restoring to the official folders, wherever they were. Recently, I came across a typescript of George Mackay Brown’s story “The Day of the Ox”, which I had tucked into a book and forgotten about. Douglas Dunn usually wrote to my home address, mixing magazine business with personal news and comment. Did his letters belong to EUSPB? I had little trouble deciding they did not. There are other scraps of correspondence and manuscript, including – literally a scrap – a poem by Crichton Smith. They are kept in my desk in a torn A4 envelope with “NER stuff” pencilled on the front.

It is not much of an archive, but it is now all that exists. Some years after leaving I asked about acquiring a few copies of the Autumn 1979 issue, with Baldwin’s essay, and was told that almost everything had “gone missing” during a move in the mid-80s. By then, EUSPB had become Polygon, soon to be expanded to embrace Birlinn. The New Edinburgh Review of No 1 Buccleuch Place had reverted to calling itself Edinburgh Review, and was now housed at No 48 The Pleasance. “And how is Lord Jeffrey?” Gore Vidal had teasingly asked me in the Assembly Rooms at the 1980 Edinburgh Writers’ Conference. I was no longer the one to say.

James Campbell was born in Glasgow. Between 1978 and 1982 he was editor of The New Edinburgh Review. Among his books are Paris Interzone: Richard Wright, Lolita, Boris Vian and others on the Left Bank, and This Is the Beat Generation. As ‘J.C.’, he wrote the NB column on the back page of the Times Literary Supplement from 1997 until 2020. His critically acclaimed biography of James Baldwin, Talking at the Gates, was reissued by Polygon in February 2021, and Just Go Down to the Road, a ‘memoir of trouble and travel’, followed in 2022.