James Campbell recalls a vital Scottish presence in the London poetry scene.

My first sight of the poetry magazine Aquarius was in Dillons the Bookstore, hard by the London University buildings in Gower Street. It was the size of a sturdy American poetry paperback, pleasing to the hand. The olive-green cover displayed an ink drawing by the Irish artist and sculptor John Behan. Birds – songbirds, presumably – appear to fly from the mouth of a laurelled youth. It wasn’t merely folded and stapled, as some little magazines were: it had a spine, indicator of a certain status. Along the spine was printed “AQUARIUS . Number 9 . 1977”.

The green issue was the first Aquarius to boast this backbone, and a well-printed interior, as opposed to typewritten script. Thanks to a Glasgow friend, Gerald Mangan – in his mid-twenties, like me, and already a regularly published poet – I recognized the name of the magazine and its editor, Eddie S. Linden. I was not yet familiar with the hobbled, hurting, sometimes humorous legends he carried as baggage everywhere he went, ancient and modern, lugged from place to place, sharing space in the plastic bag in which he brought copies of Aquarius to the gatherings he attended. His name was printed on the title page, as if illuminated. It had top billing, above the line “Assistant Editor: John Heath-Stubbs”.

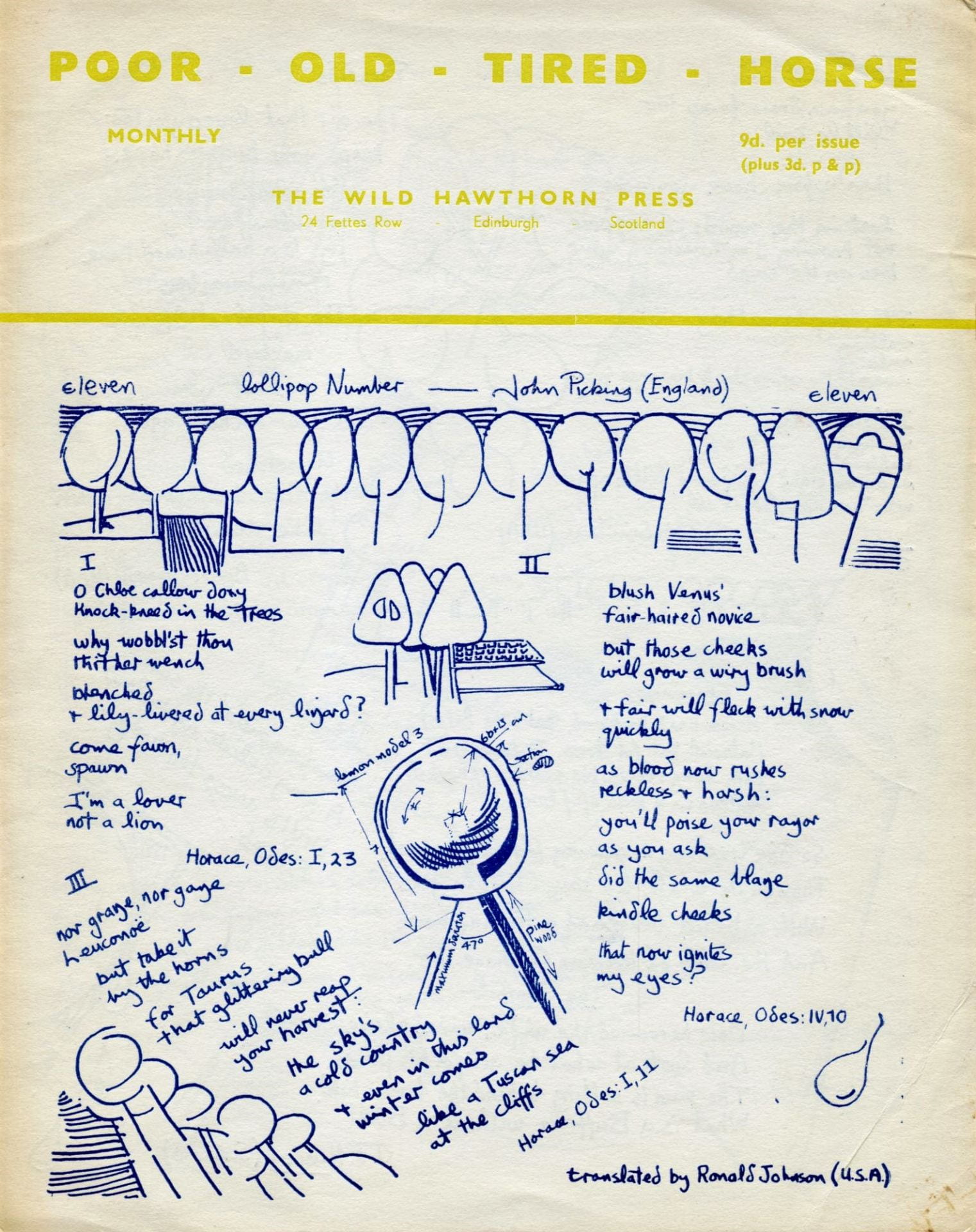

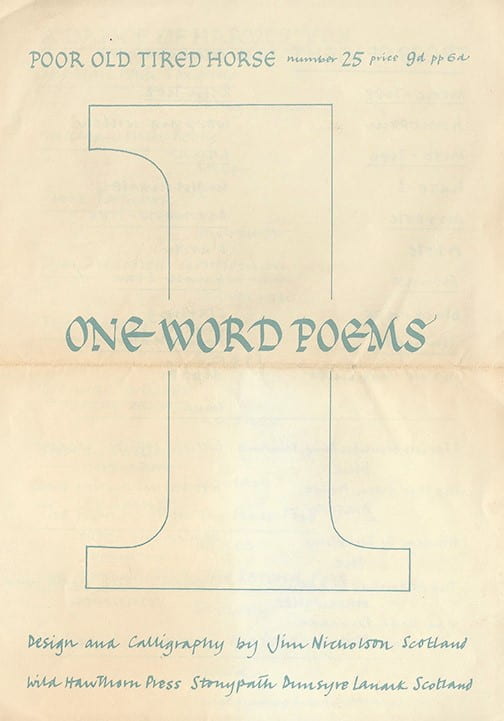

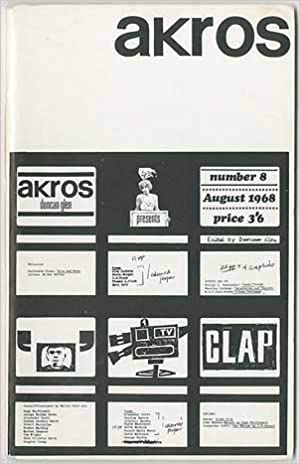

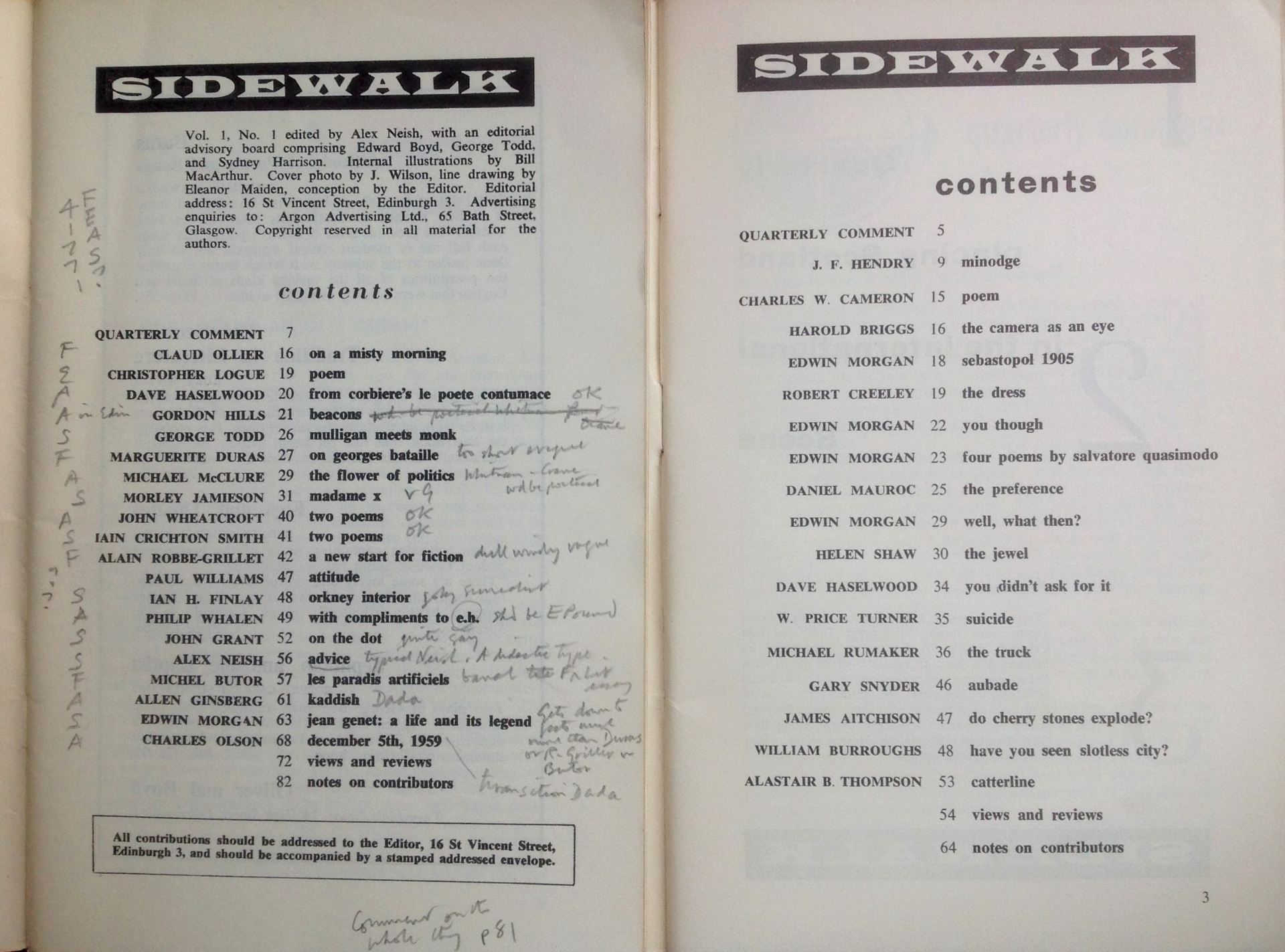

On the last page, there was a plain print advertisement headed “Magazines from Scotland”, with the names and addresses of various journals: the Glasgow-based Scottish Review, Akros – Scottish in all particulars except its address in Preston, Lancashire – Chapman, Lines Review and others, all identified as “poetry magazines”. The Scottish Arts Council had paid for the advertisement. Most of those journals aspired to some sort of schedule, even if they sometimes failed to achieve quarterly publication. Aquarius, however, was more likely to appear annually, at best. Numbers 6 to 9, for example, spanned four years.

I turned the neat green journal over in my hands. The back cover promised poems by Ted Hughes and Seamus Heaney. There was a strong Scottish contingent, with Norman MacCaig, Edwin Morgan, Alexander Scott, Tom Leonard and my friend Mangan in attendance. Two poems in the list of contents were by the editor himself, an act of opportunism customarily frowned on. One was dedicated “to my Father”, a miner in Bellshill, Lanarkshire, where Eddie grew up:

Your face has never

moved, it still contains

the marks of toil, deep in

blue. These slag heaps

now in green have

flowers instead of dust …

* * *

I was in Dillons during a stopover on the way from Edinburgh to Cambridge to attend the 1977 Poetry Festival, taking place between April 14 and 20. A number of writers associated with Black Mountain College were billed to take part, including Robert Creeley and Robert Duncan.

It was during Creeley’s reading at the Festival on Saturday evening that I got my first glimpses of the editor of the magazine I had been studying a few days earlier. Glimpses cut-off at the corners: a rightful first impression of this unique literary figure. Everything in his life – seen from both his own perspective and that of others – was jagged and torn.

The event was staged in the Student Union. Half the audience was positioned at floor level before the poet, with the remainder in the quadrangular balcony. Creeley was informal, somewhat hurried. It was ten o’clock at night, he pointed out. He read from his book Words, starting with “The Rhythm”. As a prologue he stated the title, then, without pause, breathed straight into the lines in his idiosyncratic, staccato style –

it is all a rhythm from the shutting door, to the window opening

It was mesmerising in its way: Creeley, tall and well-made, turned fifty, just going grey, with a patch over one eye socket, focused on the lines before him.

Out of the blue, a voice spoke. It came from the row in front in the balcony, yards to the left of where I sat – a voice that would have struck the right note at Ibrox or Parkhead. It was, I was to discover, invariable, unaltered by years, maturing into decades, during which its owner lived incongruously among the London literati.

Creeley had come to the end of his second poem, “Something”, and was talking about a Malaysian friend whom he was “delighted to have with us” in the audience.

From the blue: “You’re wakin’ up these young Cambridge poets. They don’t seem to know what poetry’s all about.”

Creeley sounded amused. “Well. I hope I can keep it together.”

The quip brought laughter and “Shhhhh!”

The poet leaned into another poem, “Anger” (not directed at any member of the audience).

a horrible place for self- satisfaction I rage. I rage

From the blue: “Show these bloody Cambridge poets. They don’t seem to know what emotion’s all about.”

Creeley: “Well. They’ll find out!”

More laughter. And this time a scolding voice: “Eddie!”

“Aye, go on, John, you’re a good poet.”

John? After a few further cadences and another “Shhh”, the voice shrank back under the reflux of its own rejection. Creeley observed that it was after 10.30 and that he wanted “to let you all go home”.

A short time later, in a new book by Creeley – called, as it happens, Later – I came across a poem with the title “Thanks”:

Here’s to Eddie –

not unsteady

when drunk,

just thoughtful.

It is a touching, generous poem, composed of nine four-line stanzas, with sharp perceptions dotted throughout, of “this dear man” who “takes on / the burden of your own confessions”. Eddie had evidently recited from memory one of his poems to Creeley, who in turn refers to the befuddled mind which “can remember / in the blur / his own forgotten line”. Creeley’s poem continues:

He told me later,

“I’m Catholic,

I’m queer,

I’m a poet.”

And I have no doubt at all that he told him he was the editor of a poetry magazine. Creeley would have left Cambridge with a copy of Aquarius 9, in its olive-green cover, in his luggage. [Note]

Aquarius is one of the most unusual poetry magazines ever to have been published. Not in the sense of being aesthetically strange: it wasn’t in the least avant-garde; nor was it overwrought in design, as some are. The earliest issues were quite primitive, the later ones tidy and orthodox. It was not particularly out of the ordinary to look at, but if you knew even a little of the story behind it, its very existence might strike you as beyond comprehension.

What follows may help to illustrate what I mean.

A copy of the green issue, No 9, finally came into my possession in March 2011, thirty-four years after I had handled it in Dillons. I can be specific about it, because a note from Eddie himself is tucked into its pages, dated February 28 of that year. It is written in Biro in a shaky hand, on a fragment of an old Electoral Register envelope, a mix of capitals and lower-case letters, some joined up, others standing apart from their rightful neighbours. The transcription is as accurate as I can manage:

Dear Jim. – Hear I s a copy of the 9th issue of AquARIUS. I shall be taking iT to IRISH BookFair on SAT – 5/3/2011 IN Hammersmith – Some one Look iT up iN iNTerneT – iTs being Sold in Dublin at £15 pound. It was only 60 p when I First Brought ouT. I think you were in Scotland Gerry is in iT.

The note was typical of Eddie’s style of writing for letters and prose in general. It reflected the level of his reading. If he rang me up to ask for somebody’s address, which he did quite often, it was no good dictating the name and street number over the telephone. It had to be jotted down on a postcard and sent to his flat in Sutherland Avenue, Maida Vale. Nowadays, his disability might be classified as dyslexia; but really it was just a curtailment of basic literacy, for reasons that are both simple and complex.

In 2006, I wrote a profile about Eddie for the Guardian, based on an interview I did with him at home. The introduction does not strike me now as any kind of overstatement (Eddie often claimed he was born in Northern Ireland, but after his death it emerged he was born in Motherwell):

As a tale of abandonment, rejection and plain bad luck, the record of Eddie Linden’s early years could bear little embellishment. He was born illegitimate in Northern Ireland in 1935, and was immediately smuggled out to Scotland to be kept by relatives. His foster mother died when he was ten, and when the man whom he calls “the Dad” remarried, Eddie was ejected from the family home and left on his birth mother’s doorstep in Glasgow. She would not accept him either – until then he had regarded her as an aunt – and after being shuttled from place to place he was “incarcerated”, as he puts it, in an orphanage.

When he tells these stories, which he does reluctantly, readmitting memories of “the big black car that came to take me away”, the man who recently celebrated his seventieth birthday becomes a desolate ten-year-old. Few people have had to put up with what Eddie Linden has. Few who have could emerge with his peculiar innocence and total lack of what in the West of Scotland is called “badness”.

The first issue of the magazine was published in 1969, which may be regarded as Eddie’s own Age of Aquarius. Two eminent poets of the 1940s and 50s, John Heath-Stubbs and George Barker, were involved from the start. But the proprietorial boast never changed:

“Editor: Eddie S. Linden.”

Aquarius No 1 contained poems by Barker, Heath-Stubbs, Stevie Smith and Kathleen Raine. An editorial claimed that the magazine “comes into being in response to the new wave of poetry readings” breaking over the nation’s poetry coastline in the late 1960s. George Barker remained involved. He drew the curly-topped unicorn on the front of No 8, a Welsh issue.

Sebastian Barker, George’s son and a poet in his own right, produced a book about Eddie, a ghosted autobiography that Eddie never stopped complaining about, with the title Who Is Eddie Linden. Discussion continued down the years over the absence of a question mark: an error on the part of the publisher, or a subtle device of style?

Question mark or not, “Who Is Eddie Linden” is just another framing of that universal demand, “Who am I? What am I doing here?” There were times when Eddie himself got within a yard or two of settling the matter, and those times came round whenever a new issue of Aquarius had rolled off the press and the copies were piled high in cardboard boxes in the communal hallway at 116 Sutherland Avenue. Then he knew who Eddie Linden was, and knew that the world would know: he was the man God had placed on earth to start a poetry magazine.

* * *

Aquarius often had a scattering of Scottish poets, and two issues were devoted to Scottish writing. The first, No 6, 1973, was guest-edited by Tom Buchan, later the bringer of doom to Scottish International (all issues of Aquarius were stewarded by someone other than Eddie, though he was invariably billed as editor, and offered suggestions). It stretches to 140 pages and hosts an impressive assembly, with many now-familiar names, and one or two that raise the question, “Whatever happened to . . . ?” There are ten poems by Jean Milton, for example, more than by anyone else. Once a regular presence in magazines, she seems to have vanished. Four Toms are there – Leonard, McGrath, Scott, in addition to Buchan. It also has Alan Spence’s short story “Blue”.

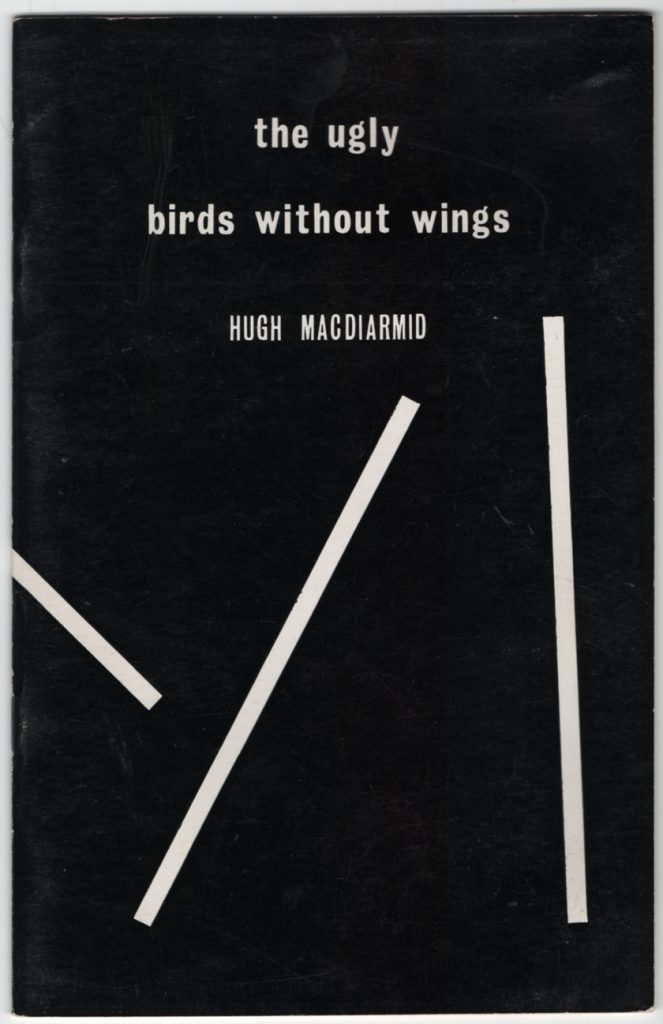

In 1979, Aquarius 11 (“In Honour of Hugh MacDiarmid”) offered a similary rich gathering. There was nothing by MacDiarmid himself, who had died the year before. Surprisingly, there is not a single Tom. Sydney Goodsir Smith, well represented in 1973, had died in the interim, but most other poets you might expect to find at the time are there, as well as new voices, such as the first appearance in print by the teenage Kathleen Jamie. The guest editor on this occasion was Douglas Dunn. There is also a symposium on the subject, “What it feels like to be a Scottish poet”, with Dunn, Alan Bold, Liz Lochhead, Edwin Morgan and others.

Gerald Mangan is present in Aquarius 11, with a poem called “Death of an Islandman”, about an émigré from the Hebrides to Glasgow, the sound in his ears of the “skirl of the pipes” replaced at the last by “noise of bottles breaking on the street”. An artist and musician as well as a writer, Mangan chronicled Eddie’s career of tragi-comic mishaps in a series of cartoons. One shows the timid editor standing at the Pearly Gates with the cherished plastic bag in hand, a beseeching look in his eye. St Peter whispers into the ear of the Almighty: “He says he’s a manic-depressive alcoholic lapsed-Catholic homosexual Irish working-class communist-pacifist bastard from Glasgow. And would you like to subscribe to a poetry magazine?”

Aquarius survived in haphazard fashion until 2002. Eddie Linden died in November 2023, at the age of eighty-eight.

[Note] I discovered that a recording of this reading exists and is available for listening at the British Library. One day in February 2023 I found myself in a carrel, present again at an event I had first attended forty-six years earlier. And sure enough the voice was heard, only a poem or two in, not quite as I had remembered it, less evidently drunk, referring to “Cambridge poets”, not “students”, as I had thought. Creeley’s spontaneous good humour came as a pleasant surprise. And the funniest part to me: it wasn’t “Gawn, Bob” but “Aye, gawn John” – more than once. When I got to know Eddie, he called me Gerry from time to time, while referring to our mutual friend Gerald Mangan as Jim.

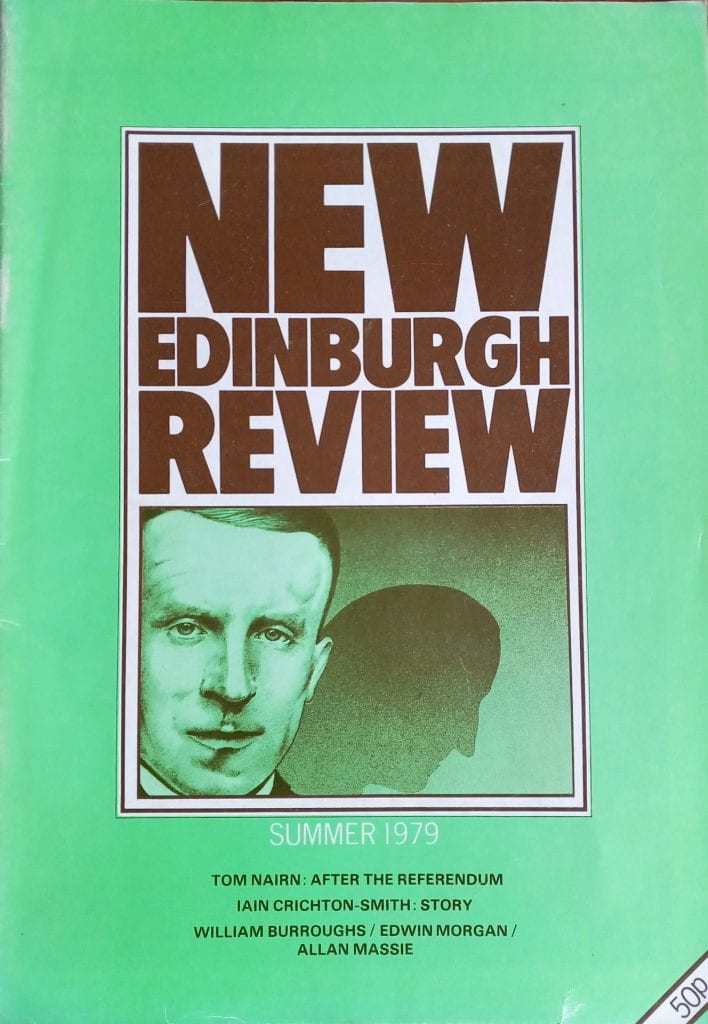

James Campbell was born in Glasgow. Between 1978 and 1982 he was editor of The New Edinburgh Review. Among his books are Paris Interzone: Richard Wright, Lolita, Boris Vian and others on the Left Bank, and This Is the Beat Generation. As ‘J.C.’, he wrote the NB column on the back page of the Times Literary Supplement from 1997 until 2020. His critically acclaimed biography of James Baldwin, Talking at the Gates, was reissued by Polygon in February 2021, and Just Go Down to the Road, a ‘memoir of trouble and travel’, followed in 2022.