Josie Giles on an anarchist newspaper from Orkney, and why it was “not absurd but inevitable”

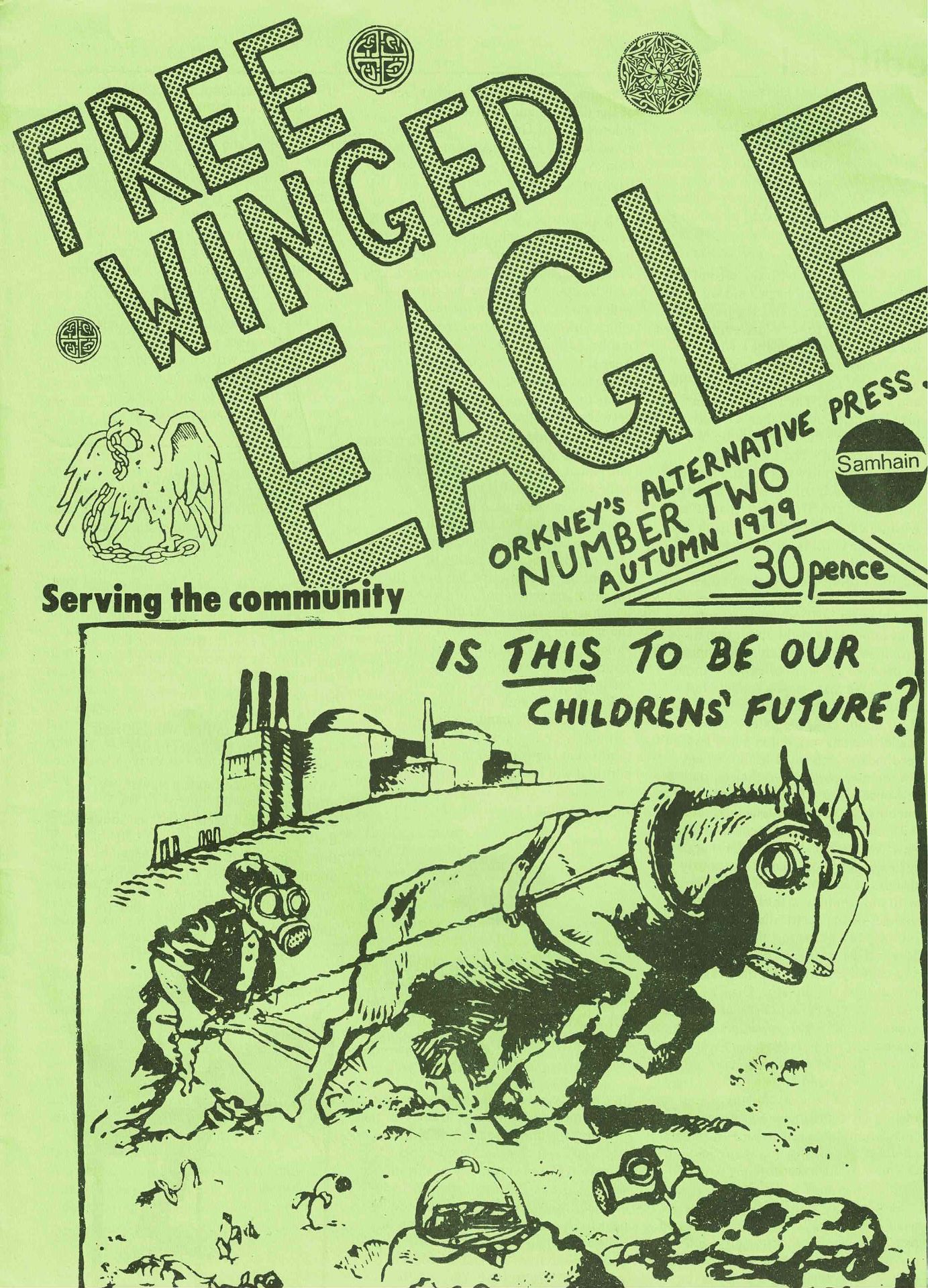

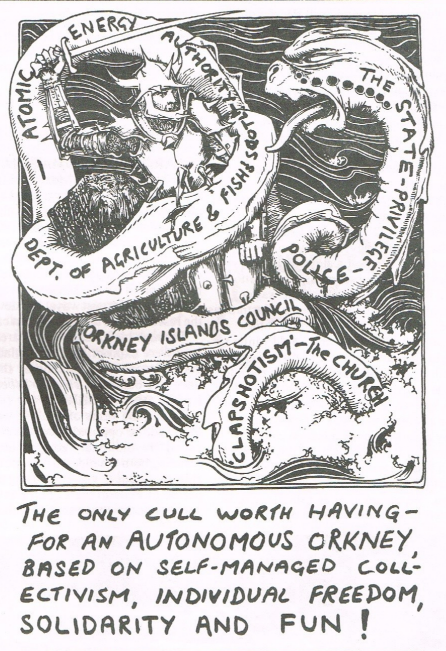

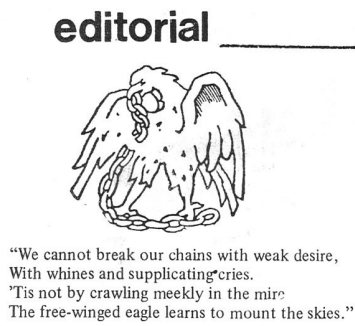

In the spring of 1979, the Free-Winged Eagle landed on the shelves of Orkney newsagents – or, at least, on three of them. Others refused to stock it. The front cover of the inaugural issue proclaimed that the magazine was for “the only cull worth having – for an autonomous Orkney, based on self-managed collectivism, individual freedom, solidarity and fun!”

The magazine, Orkney’s premier and only anarchist periodical, was published by Stuart Christie’s Cienfuegos Press, a publisher and distributor based in Sanday. Christie, known for his attempt to assassinate Franco as a teenager, had moved to Orkney following his acquittal of involvement in the Angry Brigade bombings, partly on the advice of a Special Branch officer who advised he was not safe in London. Most of the articles in the paper were written and edited anonymously, though I am informed by local sources that Ross Macgilchrist, lighthousekeeper and anarchist, was author of more than those for which he is named.[*]

The opening issue included a biography of Ricardo Flores Magon, an essay by Esther Breitenbach on the oppression of women by the Calvinist church, a case for organic farming, and a call to hit back against the police as a politicised force against working class organisation, as well as cartoons and reviews. The style mixes punk and academic analysis, political rhetoric and speculative theology, with plenty of humour. The back page of the first edition includes reviews of the Orkney West Mainland Goat Society Journal (“very informative”) and the Kirkwallian (“very progressive by school standards”).

The majority of the pages, though, were dedicated to the anti-nuclear movement in Orkney. In 1976, the South of Scotland Electricity Board sought permission to carry out exploratory drilling of uranium deposits on and around the cliffs of Yesnaby, north of Stromness. With the opening of the Flotta oil terminal in 1977, Orkney was becoming a major energy extraction site for the British economy. The North of Scotland Hydro Electric Board, the Highlands and Islands Development Board and the European Commission all supported the proposal, but it immediately faced mass local opposition.

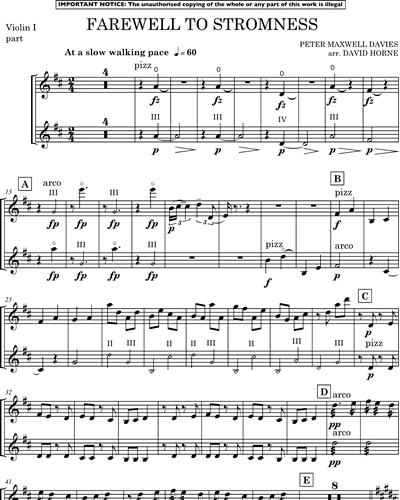

The Free-Winged Eagle’s protest against the proposed uranium mine is less well-known now than that of Sir Peter Maxwell Davies, later Master of the Queen’s Music, whose piano and voice composition the Yellow Cake Revue debuted at the 1980 St Magnus Festival, including the now much-played interlude Farewell to Stromness. The anti-nuclear movement prompted an extraordinary alliance between local radicals, prominent artists (including George Mackay Brown, whose 1972 Greenvoe was a similarly anguished cry in the face of the oil industry), farmers, teachers and councillors – a cohesive political alliance rarely if ever seen in Orkney since.

The Free-Winged Eagle sought to seize the anti-nuclear moment to radicalise local activists and propagandise for wider anarchist causes. Later issues covered Indigenous resistance to American nuclear testing and the aftermath of the Gulf of Mexico oil disaster, likely to receive significant local sympathy and understanding. An advert for An Phoblacht / Republican News (“Orkney movement? For news of the IRISH MOVEMENT, subscribe to…”) alongside a translated article from Combat Breton pushed the island envelope a little further, but editorials against the Orkney seal cull were met with local fury. As for an advert for books published by Paladin Press including Home Workshop Guns for Defense and Resistance and CIA Methods for Explosives Preparation, printed under the headline “NO URANIUM” and with a cartoon of a Viking thinking “I don’t know much about dynamite, but I’d use it”? – well, I can only speculate how many orders were placed. In the end, faced with near-unanimous and highly vocal and mobilised local opposition, the mining plans folded without the need for force, to the relief of many and, perhaps, the disappointment of a few.

Another aim of the magazine, allied with the mission of the press, was to link the wider Scottish and international radical scenes with political movements in Orkney, bridging urban/rural divides as it hoped to build local alliances. The magazine carried adverts for Black Flag (also co-founded by Christie) and the Scottish Women’s Liberation Journal, alongside reprints from various anarchist periodicals. Its vast ambitions are best indicated by a final advert: “Orkney publishing group urgently requires about 18,000 people to fill a variety of posts. […] No qualifications required. No payment will be available but job satisfaction guaranteed.” 18,000 was the entire population of Orkney at the time.

To the relief of a few and the disappointment of many, the magazine closed in the January 1981 edition, priced at 20p. I believe this was the fifth, though a complete run is hard to track down: the National Library of Scotland has only three, and the eccentric numbering obscures the British Library holdings. “Just think – in 20 years time copies of our issue number one might be considered a rare piece of Orkney ephemera, changing hands at prices up to £30!” The author’s foresight is close to perfect: this is the price I paid for copies of three issues in 2020. Two can be viewed for free at the Internet Archive, courtesy of Glasgow’s Spirit of Revolt, a vast and essential repository of Scottish radical culture.

That sincere irony is key to understanding the magazine. The Free-Winged Eagle is never unaware of the absurdity and grandiosity of its position, or its mixed reception in Orkney. The magazine is aware, too, of how people outwith Orkney would perceive an anarchist newspaper published in a rural island community. Its short run, however, is a document of a particular political moment in which the Free-Winged Eagle was not absurd but inevitable: a necessary outcome of a popular, multi-faction alliance against internationally-supported, ecologically-ruinous extractive industry. Orkney was and is a centre of energy production, a keystone in the UK’s energy economy, and contemporary conflicts with the Crown Estate over seabed rights for fishing and marine energy carry echoes of the Yesnaby campaign. The Free-Winged Eagle was shorter-lived than many periodicals produced in Edinburgh’s or Glasgow’s radical scenes, but longer-lived than many others, and the movement it sprang from is strong in local memory.

When the magazine was published, the white-tailed eagle from which it took its name, and which is seen breaking its chains with its beak in the magazine’s logo, was extinct in Scotland. The first successful reintroduction was in Rum in 1975, and the first successful breeding in Mull in 1985. In 2018, for the first time in 145 years, white-tailed eagle chicks hatched in Orkney, in the hills of Hoy.

Josie Giles is a writer and performer from Orkney, and her most recent book is Deep Wheel Orcadia: A Novel.

[*]CORRECTION: The first three issues of the Free-Winged Eagle were not distributed or published by Cienfuegos Press, but rather simply used Over-the-Water as a correspondence address for practical reasons. The paper was originally published and edited independently by Ross Macgilchrist, before being passed to Stuart Christie and Colin Badminton, who ran it for two further issues before closing. Many thanks to Ross Macgilchrist for this correction.