Ahead of our public launch event on 5 May, we’ll be running a number of blogs and podcasts sharing the memories of magazinists. To start us off, Prof Alistair McCleery offers a behind-the-scenes tour of how many Scottish magazines have been funded.

Is this thing on? Will I start?

The Scottish Arts Council, which had been established in 1967, in an early example of devolution from the overarching Arts Council of Great Britain, had a clear mission to promote cultural creation and reception across the nation. When I first became involved with it in 1988, the Literature Department was headed by the erudite and humane Walter Cairns and its Literature Committee was chaired by the energetic and diplomatic Deirdre Keaney. New projects flowed from their passion: the Edinburgh Book Festival, the Canongate Classics series, and the Scottish Poetry Library. Walter and Deirdre were both primarily responsible for the commissioning of the 1989 readership survey that in turn led to a number of key initiatives such as ‘Now Read On’ and ‘Readiscovery’.

And magazines?

I was coming to that. But you need to understand the culture Walter and Deirdre, and later (from 1996) Gavin Wallace and Derry Jeffares, created at the SAC and specifically how decision-making took place. In particular, the committee structure allowed for a great deal of transparency in decisions on the distribution of tax-payers’ money. The decisions were made by committee members who were representative of, and circulated within the wider groups of, writers, editors, and publishers as well as academics like me. Derry Jeffares, who had come to Stirling University from Leeds with enormous, entrepreneurial experience of academic publishing, built on the work of Deirdre when he took over as Chair of the Literature Committee, and further encouraged the development of writers and readers, both directly and indirectly through the support of book and magazine publishers. Derry acted as a mentor to me at this time, as he did for so many others; he constantly reminded me of my roots in the ‘Black North’ [of Ireland] as he persisted in calling it from his sophisticated TCD upbringing – even when I was enjoying his hospitality at Fife Ness, a long way from Derry and Dublin for both of us. Anyway, I also served on two sub-committees of the Literature Committee, the Mixed Arts and the Magazines, where it was a very positive experience to work alongside the likes of James Robertson.

Can you tell me more about the Magazines sub-committee?

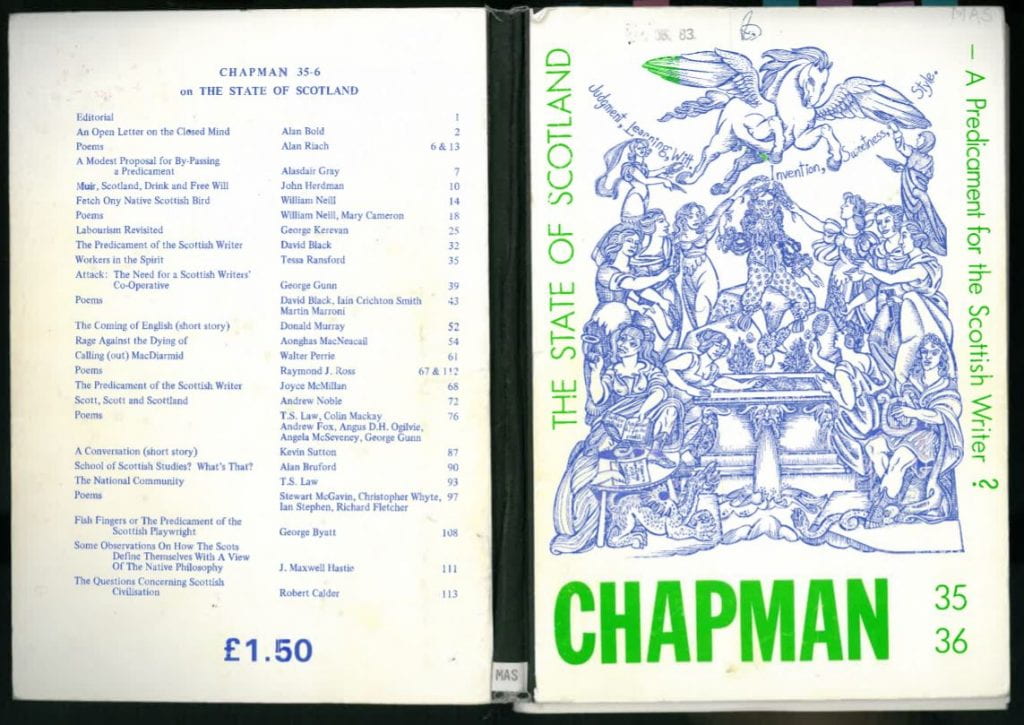

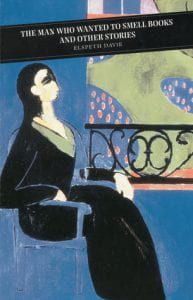

We were all committed to the importance of small literary magazines. We valued them highly as an outlet for new writers, not only in terms of seeing their work in print but also as an opportunity for editorial advice and support to shape and encourage their careers; as a place for more experienced writers to experiment without losing either their usual publisher or a readership accustomed to a certain style or subject-matter; and as a print venue where writers with similar views and/or styles could coalesce to form more influential groupings to contribute to the constant regeneration of Scottish literary culture. These might seem rather high-minded views but they were the guiding principles behind our decision-making.

To be honest, we really only encountered one persistent difficulty: staleness. Let me explain. Sometimes, editors who had typically founded a magazine, and poured a great of their own time (and occasionally money) into it, found it difficult to comprehend that they and the magazine needed to change and adapt from what it had been at its beginnings. For example, Gairm had been founded by Derick Thomson in 1951 and he was to act as its editor for fifty years. It published all the great Gaelic writers of the twentieth century from Sorley MacLean through George Campbell Hay to Iain Crichton Smith. And Derick was an absolute giant in both the literary and the academic spheres. (I also served alongside him on the Council of the ASLS at one time.) But after nearly forty years, the magazine no longer seemed as – what’s the right word – as exciting, innovative, leading-edge as it once was. It seemed to be only going through the motions. We felt that a change of editor would likely reinvigorate it but Derick, when approached informally, was very resistant to abandoning the role, even to take up an honorary editorship. You can understand why. However, in the end, we continued to support it financially because there was no sign of any other Gaelic literary magazine on the horizon.

Did you have any other criteria for funding magazines?

I think it would be fair to say that we enjoyed idiosyncrasy and encouraged diversity – of authors, topics and so on, to encourage as many readers as possible. However, there were two key principles that we insisted on: a professionalism in design and production (these being the far-off days of print); and the payment of contributors. The first was intended again to encourage readers – although I have to admit that most sales of these magazines were through subscriptions, individual and institutional, and only a few bookshops handled copies for the impulse buyer.

James Thin’s on North Bridge was an honourable exception, offering a wide range for what may have been a largely student market. The second criterion was more readily understood: we offered funding not only to support the production of the magazine but also to support the authors; you cannot create a healthy literary culture on the back of volunteer or amateur – I mean in the sense of unpaid – writers. We never used circulation figures as a funding criterion, as compared to content and presentation, but we did expect proper accounts, even of a rudimentary kind. On the other hand, with the benefit of hindsight, we perhaps should have been proactive in creating some form of central distribution system, perhaps with an existing firm, to strengthen circulation here and elsewhere.

James Thin’s on North Bridge was an honourable exception, offering a wide range for what may have been a largely student market. The second criterion was more readily understood: we offered funding not only to support the production of the magazine but also to support the authors; you cannot create a healthy literary culture on the back of volunteer or amateur – I mean in the sense of unpaid – writers. We never used circulation figures as a funding criterion, as compared to content and presentation, but we did expect proper accounts, even of a rudimentary kind. On the other hand, with the benefit of hindsight, we perhaps should have been proactive in creating some form of central distribution system, perhaps with an existing firm, to strengthen circulation here and elsewhere.

You had a later involvement with the SAC and magazines, I believe?

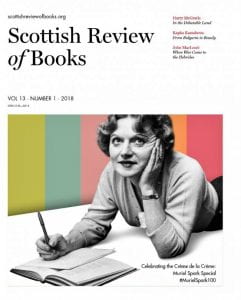

A minor one. Sometime after I left the SAC committees, in 2004 in fact, Gavin Wallace commissioned Marion Sinclair, who had also previously served on the Literature Committee and is now, of course, Chief Executive of Publishing Scotland, to write a Review of Scottish Publishing. One of our key recommendations was the establishment of a new magazine to promote Scottish writing and publishing along the lines of the very successful Books Ireland that had been going from 1976. That had acted as a very successful ambassador for Irish literary culture, particularly in its overseas distribution through the country’s consulates and embassies. Unfortunately, the British Council was less enthusiastic about a Scottish iteration. Anyway, that was the origin of the Scottish Review of Books in 2004.

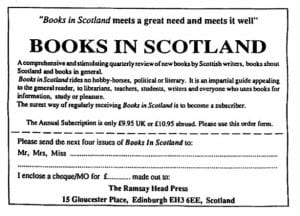

(Books in Scotland had already existed up to 1998. It had been founded by Norman Wilson of the Ramsay Head Press in 1976. On his death, his widow Christine took over as editor with the support of his son Conrad. Christine was very generous to a young academic with a large family in both employing me as a reviewer and providing my daughter and sons with lots of mint children’s books – a genre that Books in Scotland did not cover.) Where was I?

(Books in Scotland had already existed up to 1998. It had been founded by Norman Wilson of the Ramsay Head Press in 1976. On his death, his widow Christine took over as editor with the support of his son Conrad. Christine was very generous to a young academic with a large family in both employing me as a reviewer and providing my daughter and sons with lots of mint children’s books – a genre that Books in Scotland did not cover.) Where was I?

The ‘Scottish Review of Books’.

Yes. The magazine was eventually stabilised through its link with the Herald newspaper which distributed it as a supplement to its standard Saturday edition. This was due, I think, to the then links with the Herald of its Editor, the dynamic Alan Taylor. However, it still needed support from the SAC, now Creative Scotland, particularly after the link with the Herald was broken. In 2019, Creative Scotland stopped funding it and it survives now online only. Coincidentally, Books Ireland became online only in 2019 as well but it continues to be supported by the Irish Arts Council. You know, if Scotland were an independent nation like Ireland, then it might lose its…

We’d better stop there. But what about the title you’ve given to this interview?

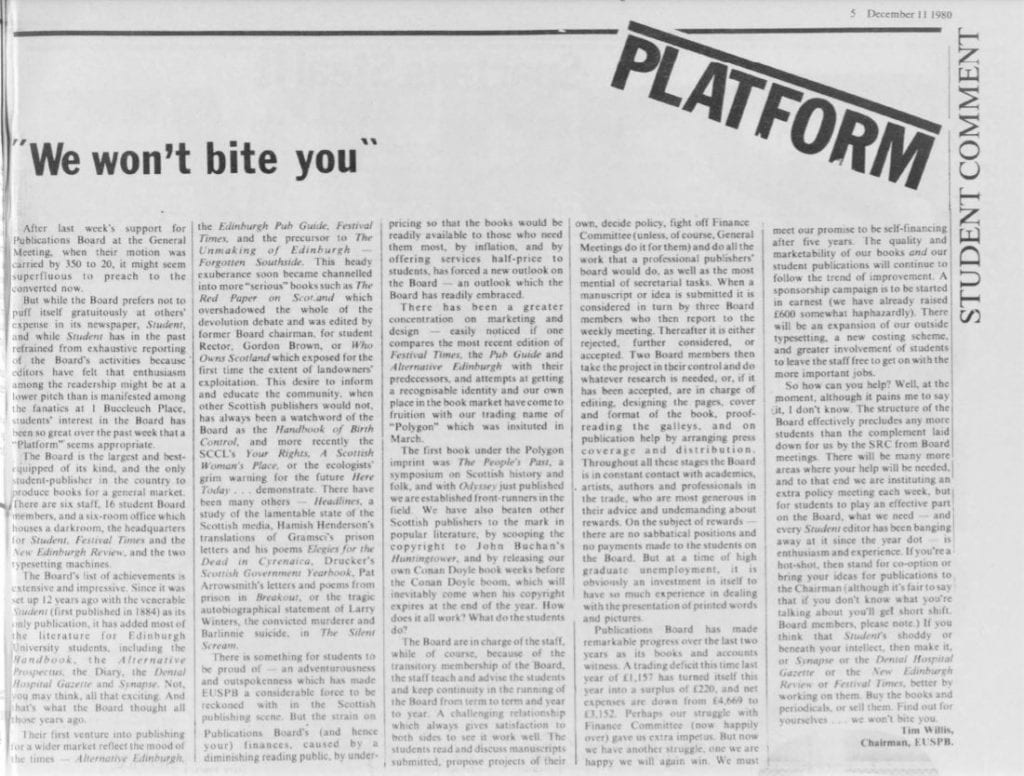

Oh, the death threat, you ask. I noted earlier that a key criterion for funding was that the magazine had to pay its contributors. We didn’t set the rate but they had to be paid. One of the editors steadfastly refused to do this and we had to withdraw support for his magazine. He then wrote to the sub-committee threatening to kill each of us next time he ran across us. It was a less litigious time and we just ignored him. And of course, it was not the first extreme reaction I’d ever received. In the 1980s, I undertook a review of small poetry presses (basically everyone except Faber and Chatto) for the ACGB [Arts Council of Great Britain] and I had to make some negative recommendations. Well, you’ve never seen vicious vituperation like that of vitriolic versifiers. But that’s for another day…

Thanks. We’ll leave it there then.

(Alistair McCleery interviewed by Alistair McCleery, St Patrick’s Day, 2021)

Alistair McCleery has published much work on the history of the publishing trade as well as on its contemporary prospects. He is the author of over 120 refereed articles and book chapters as well as some 15 books. He has written on Scottish authors from John Buchan to Neil M. Gunn, and on Scottish literary magazines from the 1920s to the 1990s.