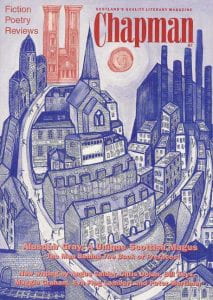

Joy Hendry looks back on the long, storied and combative history of Chapman, ‘Scotland’s Quality Literary Magazine’

The Scottish literary scene in 1970 was a veritable minefield: embattled, embittered by decades, if not centuries of neglect, distortion and misrepresentation and ignorance. Aspiring practitioners or scholars of literature like myself at the time, aged seventeen, could not be blamed for not even being aware of its existence, due to its absence from the curricula in education at every level. In terms of public recognition and funding, it was similarly invisible, deemed unnecessary, or a low priority in bodies like Arts Councils and universities.

Chapman began that year as The Chapman, a tiny, eight-page demi-quarto affair, the central impulse being simply to provide publication for poets (initially) in a scenario where much of quality was being written, for outlets very few. In no time, however, the combativeness of the scene and the struggle for scarce resources led to an editorial desire for controversy and ‘stirring it up’, especially when the founding editors had their application for Scottish Arts Council funding roundly rejected. The rude remarks made about other more fortunate magazines, and ‘established’ literary figures in The Chapman no 6 editorial, still make entertaining reading. (Straight intae the fechtin, almost…)

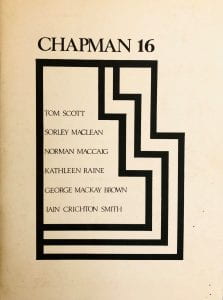

George Hardie, Hamilton-based poet, was the founder, and he teamed up with local poet Walter Perrie, whom I met in my second term at Edinburgh University, where we were both studying. He looked at my poetry and promised to publish two of my poems in the next issue. Eighteen months later, I found myself joint-editor of a literary magazine, aged only nineteen, though initially editorial policy came primarily from Walter. He wanted to place the magazine in the European and international mainstream, à la Pound, Eliot and Wyndham Lewis, and with a commitment to intellectualism and new ideas. From that lofty perspective, he tended to devalue current writing in Scotland. There was a firm commitment to quality in writing, giving airtime to new voices, including those espousing unfashionable and unpopular ideas, and to ‘speaking out’ about important cultural matters. We both wanted to avoid the destructive in-fighting going on in some of the magazines, and regretted the feuding between dominant personalities of the time. From the first, we sought out areas and authors suffering neglect or marginalisation. It’s hard to believe, now, that Sorley MacLean came into that category, as did Tom Scott and others.

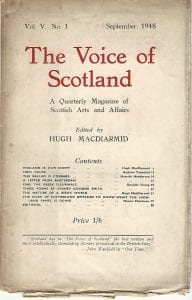

The smaller the duck-pond, the fiercer the fight among the ducks, it seems. From a UK perspective, Scottish literature barely existed, and its individual cultural mores were misunderstood, perhaps wilfully – this despite its astonishing fecundity over centuries. We were young newcomers on the scene, but it became quickly evident that ‘the establishment’ (UK and Scottish) favoured endeavour in English only, and that both Gaelic and Scots suffered as a result. There was a strong and distinct bias against nationalism, which was almost treated with intellectual contempt. (Socialist ideas and postures were more acceptable, especially Internationalist, though Hugh MacDiarmid remained largely beyond the pale in university literature departments into the 1970s.)

As Scots, we’ve always been more than keen on vicious feuding, fechtin, flyting of a terrifyingly ferocious kind, and, the duck pond being a small one, this happened big time. Individuals even of ‘the native species’, once secured in a position of power or influence, had a grim proclivity to use that to marginalise any rivals. As editors of Chapman, we were keen to promote precisely those writers whose work was being marginalised, though the magazine itself suffered as a result, its grant being withdrawn in 1977 on grounds of poor literary quality. When we’d just been publishing Tom Scott, Sorley MacLean (and others more favoured too)? Both Scott and MacLean had powerful enemies, and both had hardly been published or featured on the BBC for years.

By 1975, I had begun to get my bearings in this duckpond, and was exercising more editorial muscle, making the magazine much more centrally Scottish. We published one issue on the wonderful Rainer Maria Rilke, but when I began work on a second, mostly already commissioned, and with a third in view, I stopped dead, thinking: Why are we doing this?– and changed direction, though not entirely abandoning the magazine’s original aims and ideals. I became sole editor and redirected the magazine to prioritising Scotland – not as any backward-looking restoration, but so that the sheer quality and range of Scottish literature in English, Scots and Gaelic achieved better promotion and exposure. Inevitably that involved politics, though with a non-partisan small ‘p’.

A key moment in this process came in 1975, when we visited Sorley MacLean in Braes, on a crazy impulse arising late one evening in Sandy Bell’s, and travelled overnight to Skye, arriving drookitly on his doorstep unannounced – three of us, dishevelled toe-rags, with two dogs – to an immediate welcome. At the time he was writing his long poem, ‘Uamha ’n Oir’, the first two parts of which had already been published in English magazines. Starting off to tout for the third part, I was horrified to find out that Sorley had no expectation that any part of this poem would see publication in Gaelic, given the setup then. I immediately committed to publishing all parts written to that date, three in all, in Gaelic only, which I did (Chapman 15). Earlier that year, because of our collaborations with magazines and writers south of the border, Chapman was able to ensure Sorley’s appearance at the first Cambridge Poetry Festival, where had had made an enormous impact.

The Scottish magazine scene, in parallel, was similarly fractious and war-torn, with some though not all of the main protagonists slugging it out in their pages. Over the course of the twentieth century, some very fine magazines had come and gone: The Voice of Scotland (1938-61), Scottish Art and Letters (1944-50) and others too numerous to list here. In the 1970s, there were nine in hot competition for the limited funding: a long-running magazine in Gaelic (Gairm) since 1952, Lines Review also founded around then, published by Callum Macdonald and edited by a series of hands (1954-98), New Edinburgh Review (various editors, 1969-84), and Akros (Duncan Glen) appeared in 1965, running until 1983. Beginning around the same time as Chapman were Scotia Review (1972-1999, initially Scotia 1970-72), very much nationalist in thrust, edited by David Morrison, Lallans, devoted to Scots language (1973-) and Tocher, from the School of Scottish studies (1971-2009).

We were very much the upstarts, being the youngest editors by quite a long way. There was a Trojan horse at the time, the magazine Scottish International, founded by the Scottish Arts Council itself in 1968, edited for most of its run by Bob Tait, regarded by some as a favoured child of the Scottish establishment and in receipt of as much funding, just about, as the rest of us put together. The scene throbbed with suspicion and distrust. That SI did good and worthwhile work over its duration is beyond doubt, but it was generally felt that its stance was ‘anti-nationalist’ and the sheer disparity in the funding levels seemed deeply unfair. The very good, strongly nationalist magazine Catalyst (1967-74), similar in range of content, had been refused any funding from SAC and it was felt this could only be because of its political stance. Since most of the editors were nationalist, to differing degrees, this left people feeling wary and insecure.

Some of these were in outright war with each other; but almost all felt embattled and suspicious, guarding what little funding they had as best they could. To some extent at least, Walter and I were brought into the fold by SAC Literature Director, Trevor Royle, who became a close friend and, insofar as he could, supporter. Weary of the feuding, Trevor and Walter dreamed up a magazine association (SCAMP – Scottish Association of Magazine Publishers) which brought all the editors together in an attempt to maximise distribution. Before long we became friends and collaborators, organising events, holding regular meetings and employing magazine reps. Sadly, perhaps, the only thing that really worked, distribution-wise, was yours truly trudging round universities, trawling pubs, selling hand to hand. My record in one day was 144, sold at The East Kilbride Mod in 1976. Walter and I tried hard to foster a quasi trade-union mentality amongst editors, with at least some success, and there’s a hangover from that amongst editors working today. An abortive attempt to revive SCAMP was made by Gavin Wallace and myself in the early 2000s, but it didn’t (and couldn’t) work.

In editing Chapman, I didn’t allow feuding or gratuitous nastiness in its pages. While quite prepared to champion one writer to the chagrin, perhaps, of another, I did so for literary reasons and managed, over time, to ensure that both ‘parties’ appeared in its pages. At no time did I allow anybody, or any body, to dictate who or what I should publish, though I was open to ideas from everywhere and learned what I needed to learn from wherever I could.

Thanks to benign and careful manipulation, especially from SAC directors Trevor Royle and Walter Cairns who argued tirelessly for more support for literature, the whole literary scene in Scotland became much more harmonious and well catered-for, with everyone involved – writers, publishers and the rest – feeling that we were working towards common goals to the benefit of Scotland as a whole. Indeed some, myself included, now lament the lack of a good centrally disputatious issue, because things are maybe just a bit too cushy and ‘dumbed down’. I always tried to be even-handed, making literary quality, insofar as my judgement allows, my principle criterion; losing friends from turning down their work and publishing people with whom I was not exactly ‘at one’. I even published work I found personally abhorrent or distasteful in some way, because it had some quality or other I thought important.

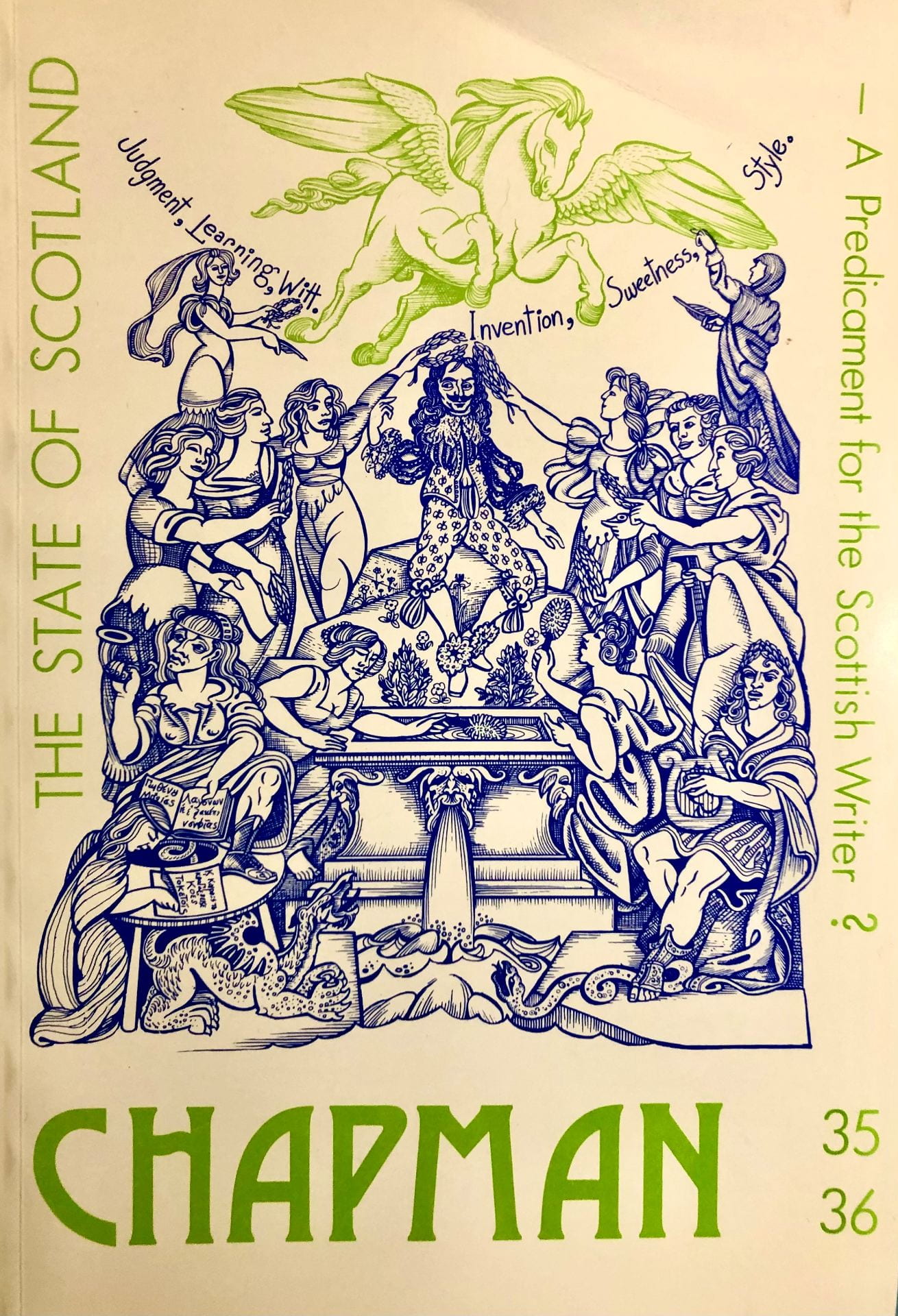

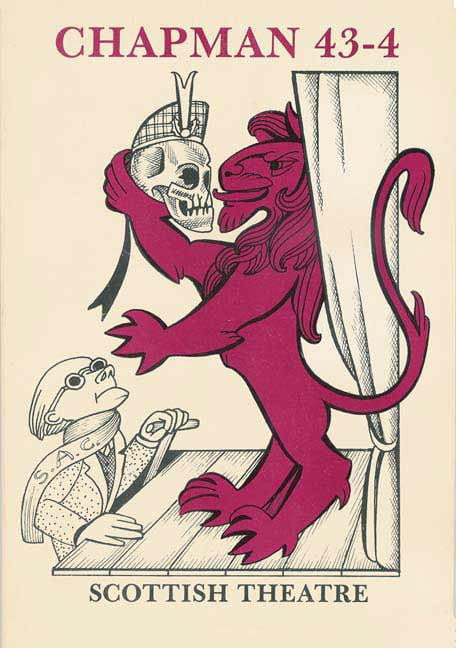

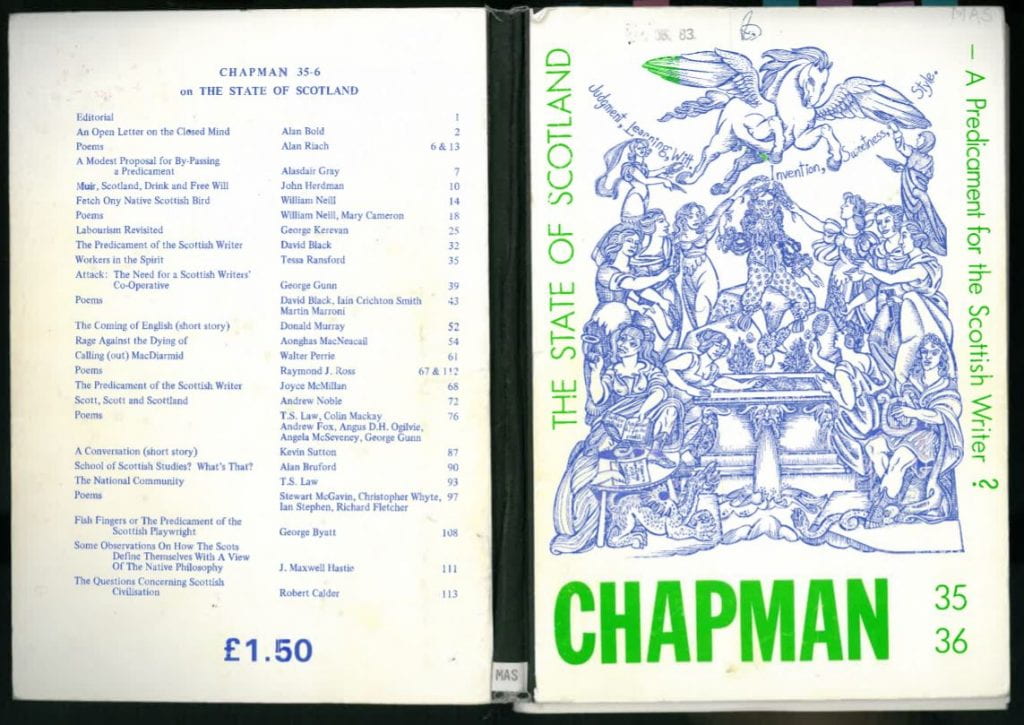

From issue to issue, I would look out for some area that needed exploring, or radical change, and often devote an entire issue to discussion of that area of Scottish life; Scots: the Language and Literature (No. 23-4, 1979) looked at the language across the boards and tried to adumbrate what action in each aspect was needed to better its status and condition; Woven by Women (No. 27-8, 1980) was the first ever attempt in Scotland to open Pandora’s Box and look at the contribution of women to culture in the twentieth century. Another important issue was No. 35-6, The State of Scotland: A Predicament for the Scottish Writer? (1983) in which writers aired views about Scottish identity, its pros and cons, from all the political airts and perspectives (that caused a storm). And the Theatre Issue (No. 43-4) provoked a major re-think of the whole theatrical scene, pointing to the absolute necessity of giving more support to ‘the native industry’. The National Theatre we now have grew uninterruptedly, though not without huge difficulty, out of that issue, and both the magazine and I were heavily involved in the process right along the line.

Chapman of course had its critics, and its detractors, some of whom tried to accuse it of unthinking Tartanry, or ‘narrow nationalism’, neither of which charge sticks at all. One of the things I most value in hindsight is serving on the committee, headed by Professor Sir Robert Grieve, which produced A Claim of Right for Scotland (1988), which lead directly to the Scottish Constitutional Convention and the Holyrood Parliament. I find it amusing, and quietly satisfying, to observe writers gradually adopting positions which they had previously criticised the magazine for espousing, for example, realising the potentials of Scots language, which they declared had no future. And many swung away from looking primarily to influences from south of the border or across the Atlantic to realise for themselves the sheer amazing originality, fertility, and creativity that has emerged from Scotland over the centuries. Now, it is no longer deeply un-cool and backward-looking to be Scottish, but something to exploit and enjoy. At no time did I completely ditch the policy to publish international work, but, having realised in those early years just how much had to be done to build a deserving cultural framework here, it simply made no sense to do anything other than consider, as priority, the needs of Scotland and its writers. From about 1995 onwards, as huge progress was made, I felt able increasingly to publish work from all over the world.

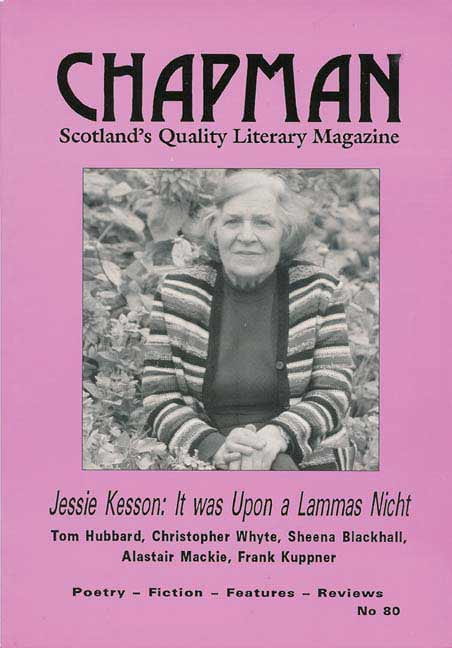

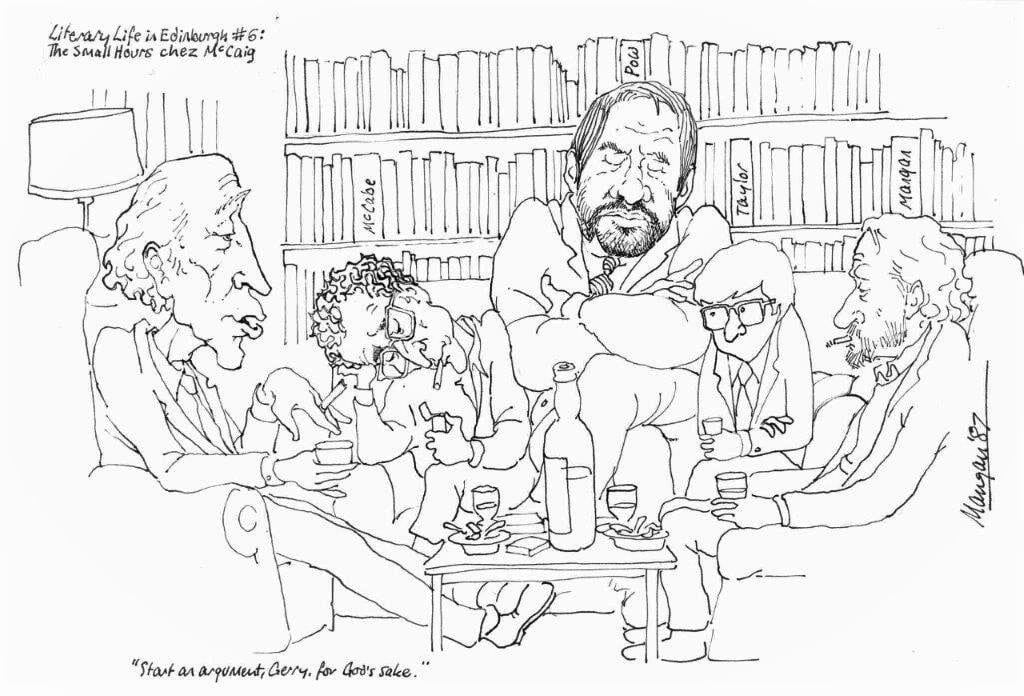

And what of being a woman in that very male world (especially up until about 1980)? I think I am the first solo woman editor of a magazine, certainly a literary magazine, in Scotland. It’s been my great fortune to know and work with so many of the mainly male writers of the Scottish Literary Renaissance. I never felt, or was made to feel, in awe of any of them, though one or two gave me rather less regard than I might be due because I am a woman, and at first such a young woman. Without any self-consciousness at all, I approached even Hugh MacDiarmid as someone I could interact with on equal terms. I spent wonderful evenings with Norman MacCaig, Hamish Henderson, Iain Crichton Smith, Tom Scott, Alasdair Gray (who provided our covers for years) and many others; and those I didn’t meet so often were hugely supportive and always happy to write for me: Edwin Morgan, George Mackay Brown and many others. I missed knowing Helen B Cruickshank, which I deeply regret, but became very friendly with Jessie Kesson and Naomi Mitchison, both of whom I published regularly.

I would say that most (not all), like MacCaig, Crichton Smith, Hamish Henderson and others, appreciated me more for doing what I had done, because I was a woman. I used the magazine to encourage and support as many women as I reasonably could. However I am certain that both Chapman and I suffered in being unthinkingly passed over for many benefits and ‘official’ opportunities (in respect of status and reputation) due to two factors, one being my gender, and the other that Chapman operated independently from any officially-recognised institution. Being the particular age I am, I luckily ‘caught’ that older generation in a crucial cross-over period from neglect to recognition, but I notice women even ten years younger have a self-confidence which was systematically knocked out of the age-group I was born into. Looking back, I am narked, feeling I could in fact have done quite a lot more. In 1980, it was still possible for an established Scottish male poet to remark, when I probed him during researches for the Woven by Women issue: ‘Scottish women poets? You mean there are any!’ Nobody could ever say that now.

I think there were in fact advantages in my being female in this very male world, simply because I didn’t have to cope with having a ‘male ego’ myself, and could look dispassionately, sometimes even amusedly, at the trouble caused by the inter-tussling of the men, and see it clearly for what it was. Chapman has never been a vehicle for my ego, but a means to get certain things achieved in Scotland. I’m trying, nearing 70 now, finally to pay some attention to my own ego and personal needs – though finding it more difficult than one might expect to switch focus. But I am gratified that both Chapman as a magazine and I as an individual have played a significant role in the journey towards the devolved, thriving and much more robust Scotland we now enjoy.

Joy Hendry is a poet and editor based in Edinburgh. In 2019 she was honoured by the Saltire Society as one of the ‘Outstanding Women of Scotland’. In 2020 she became the inaugural winner of the Scottish Poetry Library’s Outstanding Contribution to Poetry in Scotland Award.