Sarah Leith investigates some mid-century satire on the ‘tartan monster’

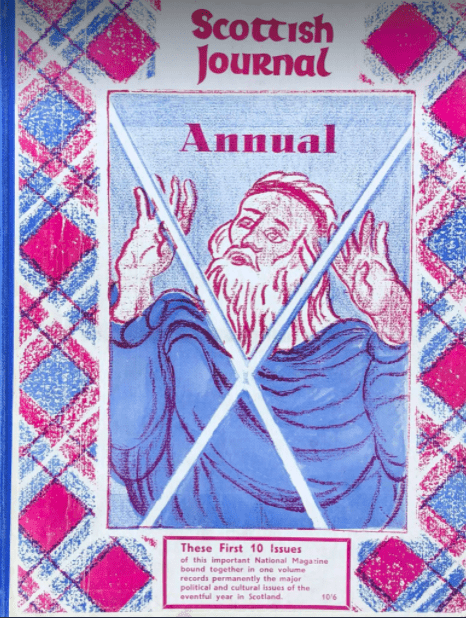

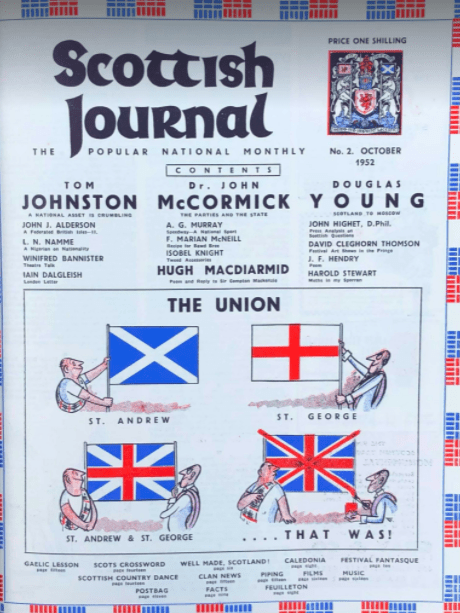

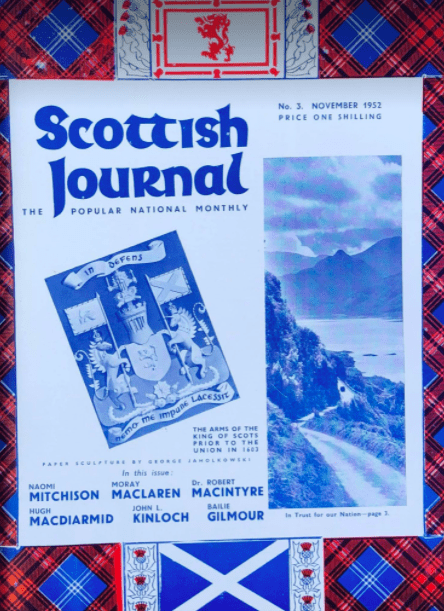

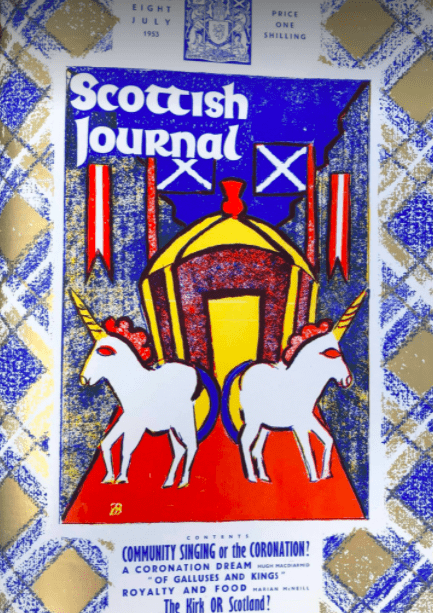

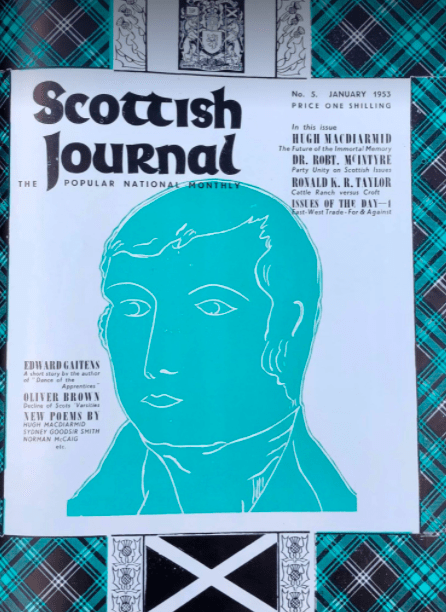

In September 1952, a new periodical appeared on the Scottish literary scene, aiming to paint a ‘month by month picture of Scotland – our doings, thoughts, humours and aspirations’.[1] This magazine was the devolution-seeking Scottish Journal (1952-4), edited by Hugh MacDiarmid and Compton Mackenzie (amongst others). It emerged as questions of Scottish self-government were becoming more serious, first via the Scottish Covenant campaign in 1949-51 – which gathered up to two million signatures calling for Home Rule – and then by the 1952 Catto Report on Scotland’s share of UK expenditure and revenue, which strengthened calls for administrative devolution and led to a Royal Commission on Scottish Affairs (1952-4). The possibility of even minor constitutional change prompted reassessments of the national self-image, looking backwards to contemplate a different future. In the first number of Scottish Journal, we find Australian John J. Alderson’s speculations about a federated Britain printed alongside Harold Stewart’s intriguingly titled ‘Moths in My Sporran’.[2] While we cannot be exactly sure who Scottish Journal’s Stewart was, it is possible that he may be the Daily Record journalist who authored the novel Bats in the Belfry (1935).[3] Although his identity is uncertain, we do know that he embraced the Scottish Literary Renaissance critique of sentimental visions of Scotland.

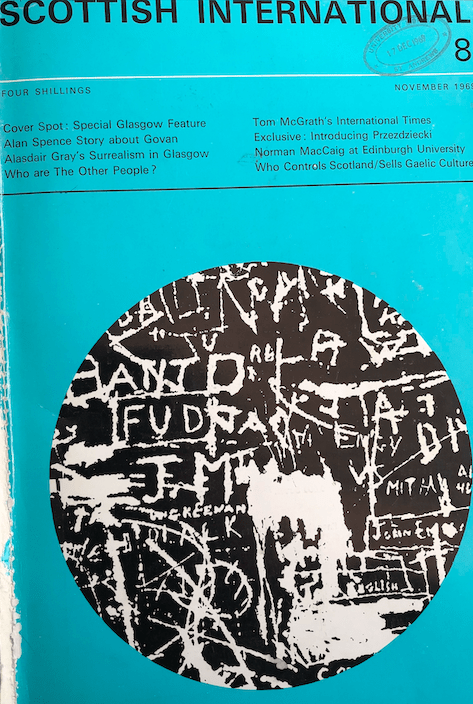

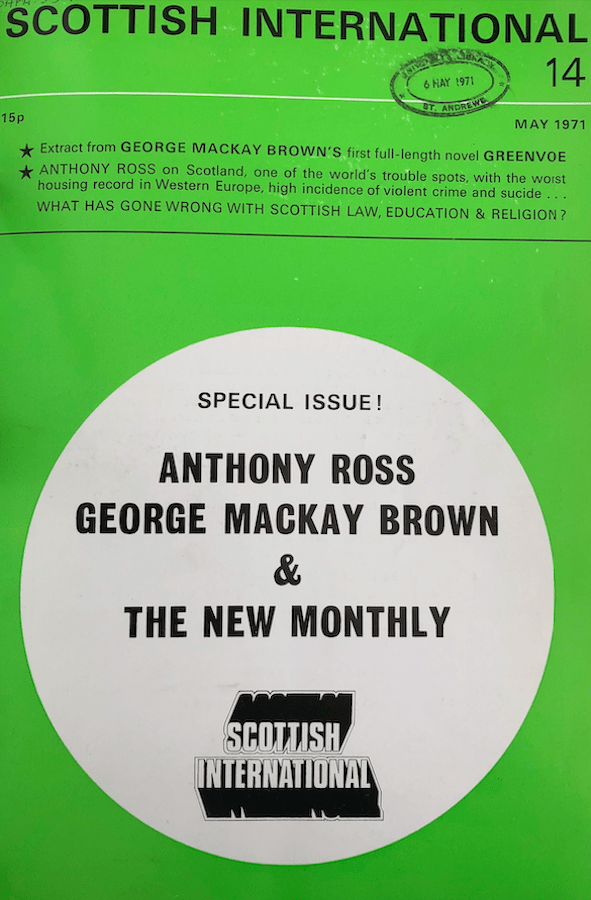

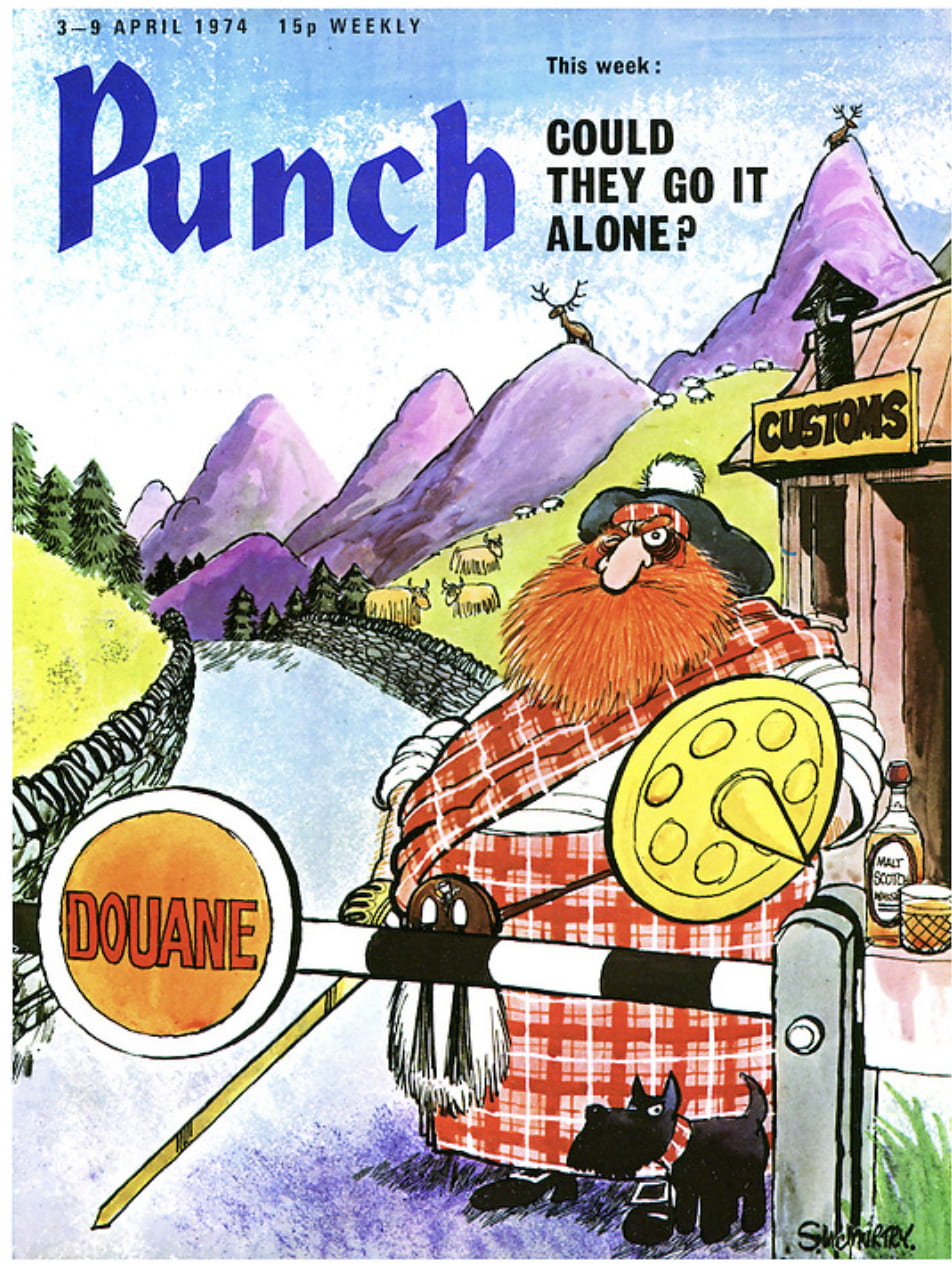

Evoking images of decaying tartan and moth-eaten fur, this article is recognisably part of a much broader battle against ‘inauthentic’ images of Scotland and Scottish culture, one that stretched across the twentieth century from the Scottish Literary Renaissance to Tom Nairn’s famous evisceration of the ‘vast tartan monster’ in the Red Paper on Scotland (1975), and far beyond.[4] Literary and political magazines played their role in this critique. It is clearly present in the 1968 launch issue of Scottish International, which promises ‘to look for what is really there [in Scotland], and to call people’s attention to it’.[5] A sobering high-point in this endeavour is Father Anthony Ross’ article ‘Resurrection’ (May 1971). Ross, the University of Edinburgh’s Catholic Chaplain, emphasised ‘the struggle of living here in the fog of romantic nostalgia for a world that never existed, and lies and half-truths about the world that does exist’.[6] For him, Scotland was ‘sick and unwilling to admit it. The Scottish establishment at least will not admit it. The tartan sentimentality, the charades at Holyroodhouse, the legends of Bruce and Wallace, Covenanters, Jacobites, John Knox and Mary Stuart, contribute nothing towards a solution’.[7]

‘It might help’, Ross argued, ‘if we could set aside for a time the image of Scotland presented in the glossy magazines which decorate our station book-stalls’ and consider instead

the distressed girl of sixteen drifting round the city, turned out of a home she had five months ago, pregnant, it was believed by her own brother […] or the defeated woman who longs for the day when another of fourteen children will leave school and she can tell him to go and look after himself […] The list could stretch until this [book] was full, a roll call of those people in Scotland whose tragedy is buried in statistics but who challenge all the conceit with which we brag about our great traditions.[8]

Attacking a different set of myths, concerns about the decay and appropriation of Gaelic culture were raised in Scottish International in November 1969. Donald John MacLeod’s ‘The Sellers of Culture: A Look at Interpretations and Some False Interpreters of Gaelic Culture’ blamed Lowland tourist and native ‘interpreter’ alike for the perpetuation of ‘false’ images of the Highlands.[9] MacLeod observed a circular quality to this traffic in myths:

In interpreting their native society to the Gall, the exiled Gaels – both because they wish to popularise and so perpetuate the culture and because they value acceptance by the city middle class – have amended their model to make it as acceptable as possible to the non-Gael. The interpreters on the other side of the fence – those Lowlanders, from comedians to scholars, who feel qualified to comment on Gaelic culture – have contributed an image of their own to which that of the native interpreters has gradually assimilated. This popular stereotype often appears in humorous caricature – the Highlander as a kilted, whisky-sodden, sentimental giant.[10]

‘In fact’, MacLeod noted, and ‘(as many may have already suspected), most Gaels do not wear kilts, sing all the time, compose village-poetry, or speak Gaelic all day long’.[11]

Now let us return to the September 1952 edition of Scottish Journal, and the perturbing predicament of Harold Stewart. ‘Moths in My Sporran’ only appeared in three editions of Scottish Journal, but Stewart’s three columns wittily mock the pervasive images of kilts and kailyards that were sold both to visitors and to the Scots themselves. Stewart’s cheeky title implied that authentic Gaelic culture, symbolised by the sporran, and used to (mis)represent both the Highlands and the Lowlands, had been left to fester and rot in a dusty cupboard, while at the same time being abused for financial gain. Scottish Journal was not as radical as Scottish International, but it did have a clear sense of what the Lowlands and the Highlands were not, and it poked fun at those it blamed for commercialising a false and tawdry image of the nation.

The first ‘Moths in My Sporran’ column emphasised both the alleged fakery of popular tartanry, and the uses and abuses of Highland culture. Through his use of satire, Stewart highlighted a worrying Bonnie Prince Charlie problem:

Then there is the traffic in Bonnie Prince Charlie’s lovelocks, based on the historical fact that the Young Pretender, during his brief bid for a throne, went up and down Scotland scattering curls in all directions. Satisfied as we are with the Board of Trade returns which show that some 1,000,000 bushels of the Chevalier’s chevelure are sold to romantic visitors annually, there is a darker side to the business.

For one thing, it deprives the stranger of the pleasure of seeing Scotland’s handsomest dog, the golden Labrador, which vanishes from view at the outset of every tourist season, leaving its hair behind in antique lockets and pathetically shaded sachets of silken ribbon. And while it probably does the shorn bowwows no harm to go to the dog-racing tracks and masquerade as greyhounds for a time, I am against the practice. I invariably back those dogs.[12]

The Young Pretender’s dusty and moth-ravaged ‘locks’ may have been on sale in Edinburgh at festival time. ‘Hail Ceilidh-donia’, the third ‘Moths in My Sporran’ column, satirised the fashion for ceilidh parties held by members of the Scottish Labour movement in the period, including by Hamish Henderson (leader of the modern Scottish folk revival movement) at the Edinburgh People’s Festival, as well as the ceilidhs held by the Bo’ness Rebels from 1948 onwards.[13]

For Stewart, the first People’s Festival Ceilidh (1951), was no better than either J.M. Barrie’s sentimental Kailyard novels or Edwardian song-collector Margery Kennedy-Fraser’s Anglicised folk-song. In ‘Hail Ceilidh-donia’, Stewart began by ‘remembering’ that ‘a thinker firmly on returning home from the Rothesay Mod’ had explained to him that ‘only in the ceilidh does the essential nature of the Gael find full and free expression’.[14] However Stewart’s description of this ceilidh presents his reader with a palpable atmosphere of fakery as he recalls ‘the subtly nostalgic scent of peat-reek in the room. Or maybe the aroma came from the fag-ends smouldering on the carpet. No matter. The atmosphere was just right. There was the singing! […] And poetry!’[15] It is in his description of the ‘Highland’ dances that Stewart’s wit and frustration reach their peak, as he describes the dancers as enjoying

The rumba (named from the wave-washed Hebridean isle of Rum [sic]), the conga (invented, as the title implies, by Conn of the Hundred Battles), [and] the mamba (traditionally derived from Mambeg), [which] invited our light-springing footsteps to trample the floor in the ancient rhythms[16]

In Stewart’s opinion, the folk revival was not only promoting a false image of Gaelic culture but also actively repressing this culture and spirit. Of course, Hamish Henderson intended the folk revival to unearth and liberate authentic Scottishness, not to traduce it. Perhaps a suspicious Stewart simply had the wrong, unromantic end of the stick: arguably, Henderson and his fellow folk revivalists were just as averse to cultural appropriation and nostalgic peat-reek.

As Scottish Journal’s ‘Moths in My Sporran’ columns show, then, pointed critique of sentimental Scotland and its ‘great traditions’ did not vanish for a time during the mid-twentieth century, and an impulse to expose harsher and more unsettling truths about Scotland exists alongside popular tartanry.

Sarah Leith has just completed a PhD at the University of St Andrews, on repression, counterculture and Scottish national identity, c.1926-c.1967.

[1] ‘The Journal of a Nation’, Scottish Journal (September, 1952): 1-2 (p.1).

[2] John J. Alderson, ‘A Federated British Isles’, Scottish Journal (September 1952): 8-9; Harold Stewart, ‘Moths in My Sporran: Pss! Wanna Nice Feud?’, Scottish Journal (September 1952), p.9.

[3] Many thanks to Dr Paul Malgrati for helping to find a possible identity for Harold Stewart.

[4] Tom Nairn, ‘Old and New Scottish Nationalism’, in The Red Paper on Scotland, ed. by Gordon Brown (Edinburgh, EUSPB: 1975)

[5] Scottish International (January, 1968): cover-p.3 (p.3).

[6] Anthony Ross, ‘Resurrection’, Scottish International (May, 1971): 4-10 (p.6).

[7] Ibid.

[8] Ibid., p.9.

[9] Donald John MacLeod, ‘The Sellers of Culture: A Look at Interpretations and Some False Interpreters of Gaelic Culture’, Scottish International (November, 1969): 49-52 (p.49).

[10] Ibid.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Stewart, ‘Psss! Wanna Nice Feud?’, p.9.

[13] Harold Stewart, ‘Moths in My Sporran: Hail Ceilidh-donia’, Scottish Journal (November, 1952), p.5.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Ibid.

[16] Ibid.