Richard Crockatt remembers Bob Tait (1943-2017), founding editor of Scottish International.

This tribute was first published by Sceptical Scot, shortly after Tait’s death in December 2017, and is reproduced by permission of editor David Gow.

It is forty-five years since I last saw or corresponded with Bob Tait but news of his death has nevertheless come as a shock.

For a short period in the late 1960s when I was a student of English Literature at Edinburgh University, Bob was the most important person in my life. Both friend and mentor, he gave me access to new experiences which became integral parts of my life. The obituaries tell the story of his public career and influence. I want to offer a personal sidelight on a period of Bob’s life when his public career was still in the making.

I met Bob in autumn 1966 at a meeting of a group he had formed to study the workings of the media in society. That evening we discussed Marshall McLuhan’s Understanding Media which had been published only two years before. It was a revelation to me, uniting literary and sociological techniques in a way none of my literary studies had prepared me for. But Bob wasn’t interested in just understanding Understanding Media; he wanted to use it as a political tool for unmasking the distortions and manipulations fomented by the press. To that end, at subsequent meetings Bob invited us to take apart newspaper pages, looking for the largely unconscious tricks and sleights of hand the media used to convey subliminal messages.

I’m not sure I understood exactly what he was driving at but it seemed an exciting way of approaching all kinds of writing, including literary texts, and that’s where in the end I found the payoff. Coincidentally Bob introduced me to the work of Ezra Pound whose imagism seemed consonant with what Bob was doing with media texts in that language was taken to be constitutive of reality not simply a reflection of it. For a number of years after that, Pound was the most important of writers for me.

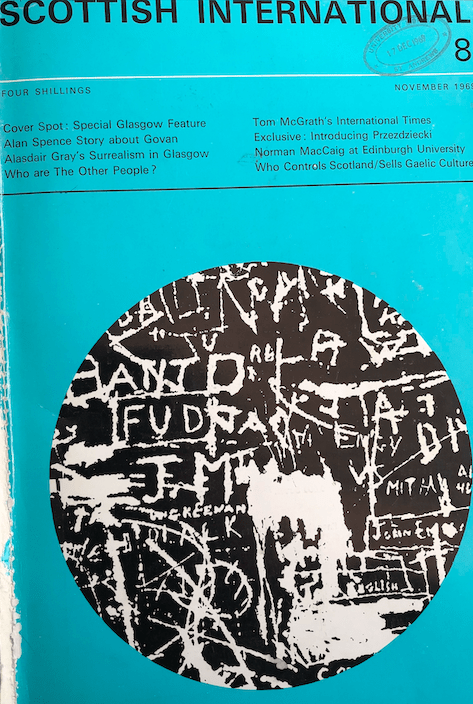

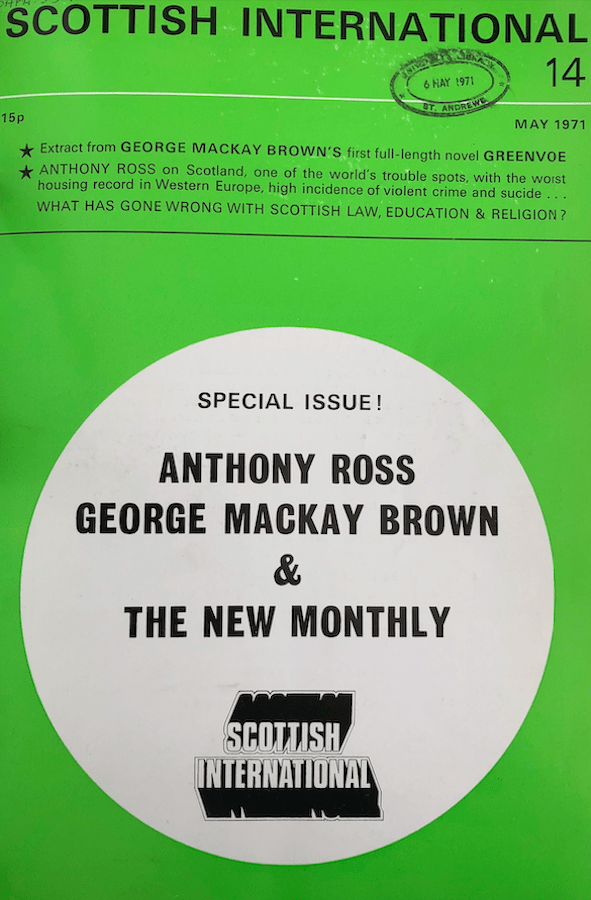

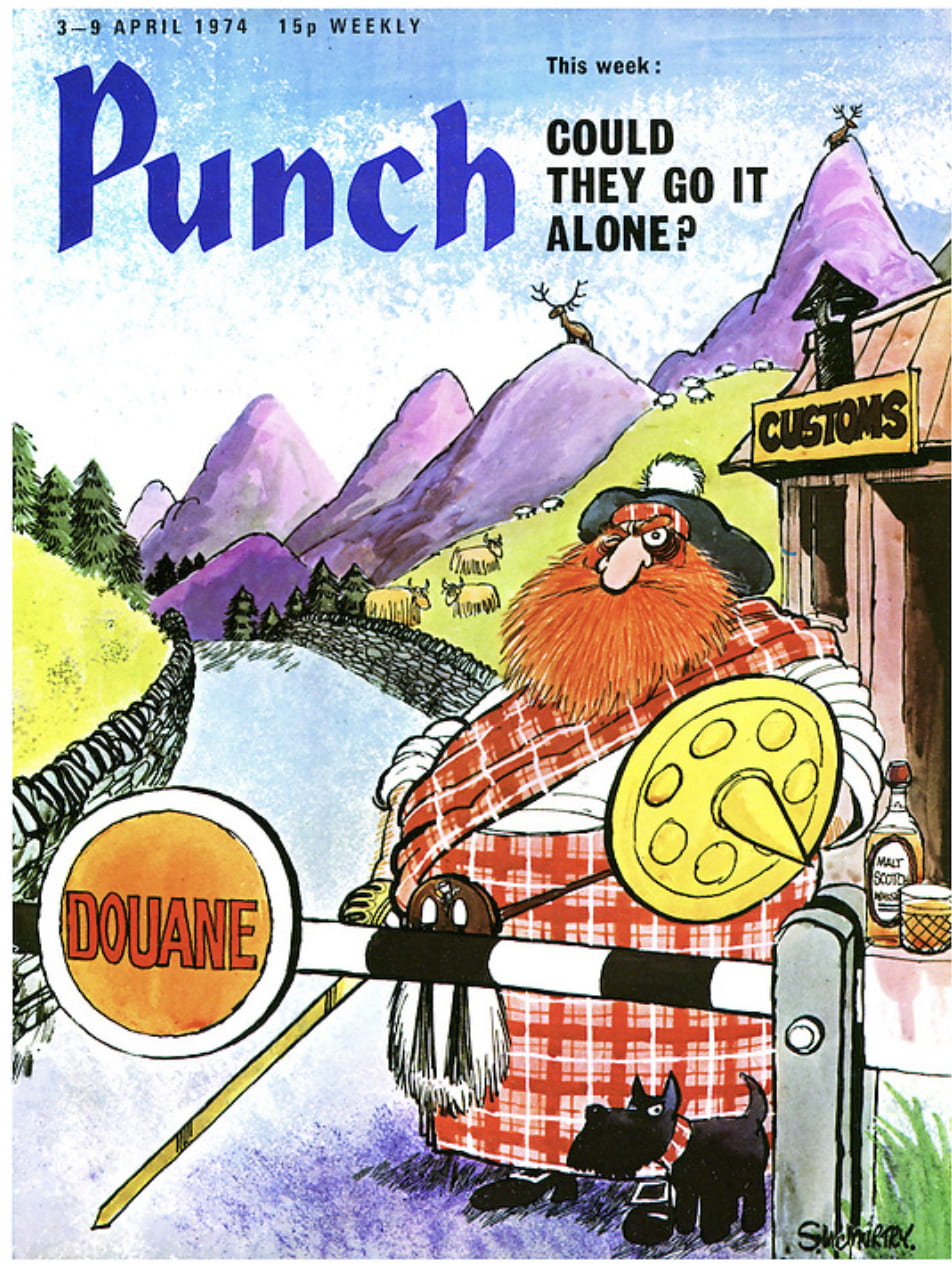

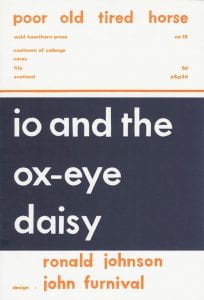

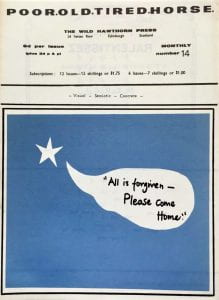

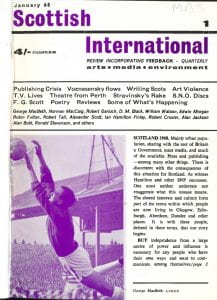

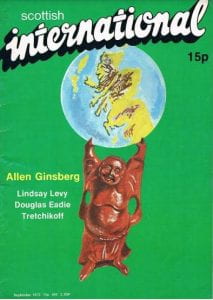

For Bob, who was a doer as much as a thinker, the outcome of these discussions and ideas had to be something tangible and it came in the form of a magazine he produced called Feedback. To my knowledge only two issues ever appeared, the first in late 1966 and the second in Spring 1967. A third was promised but I believe it never came out. By this time Bob was working on the production of Scottish International Review (SI) whose first issue, backed by the Scottish Arts Council, appeared in January 1968. The first six issues carried the message ‘incorporating Feedback’ on the masthead, so in Bob’s eyes there was a seamless progression from one publication to the other, albeit SI had a more explicit Scottish nationalist agenda.

SI is now the subject of academic articles and PhD theses about the Scottish literary renaissance. At eighteen years old and an anglicized Scot who had spent his teenage years in England I was scarcely aware of the larger picture. All I knew was that I was getting at least as much of an education from Bob as I was from the University. Bob was only four years older but he was a postgraduate student in philosophy, formidably well read, and in touch with the larger political world of which I was only distantly aware. Above all Bob was a friendly and encouraging presence, something like an older brother, and endlessly supportive off my efforts in writing. I was committed to the success of SI which I sensed was something new and exciting. I sold copies of SI on the streets and corridors of the university. Returning the confidence, he gave me a book of poetry to review for the first issue of SI to which I gave far more attention than any of my university essays.

I saw a lot of him in those years from 1966 till 1969 when I graduated. On occasions we would meet up at Bobby’s bar for lunch or an evening drink. He invited me a number of times to his house for meals with his family where we would be treated to records of Bartok and Shostakovich and discussion of books and writers. I went numerous times to the Catholic Chaplaincy in George Square which was the headquarters of SI as well as a literary gathering place. Bob was on close terms with leading figures such as Robert Garioch, Edwin Morgan, Ian Crichton Smith, Norman MacCaig, Alan Bold and many others. There I also encountered Father Anthony Ross, the charismatic and tender but nevertheless formidable Catholic Chaplain whose occasional rages were a sight to be seen and preferably avoided. Bob and he seemed very close.

The last time I saw Bob for any length of time was in the summer of 1969 at Gairloch where he was on holiday with his family. For me there is a halo around those days of long sunny walks, family meals and conversation since after that it was never the same again. I left Scotland that summer and life took me in other directions. We corresponded for a couple of years – Bob wrote long, engaging and affectionate letters – but over time we lost contact.

It is the case, however, that in the intervening years Bob has come to mind on countless occasions. To my lasting regret I never contacted him again. Would it have been a disappointment if I had? Is it not better to leave things as they are — or were? I now no longer have the choice. What I do have is the experience of having known an incomparable individual who has left a lasting imprint.

Here is The Scotsman’s obituary of Bob.