In our next inky recollection, D.M. Black looks back on a prodigious stack of poetry magazines and cultural reviews.

For more memories, and to share your own, please come along to our online event on 12 May.

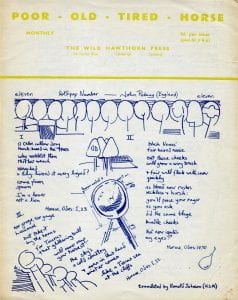

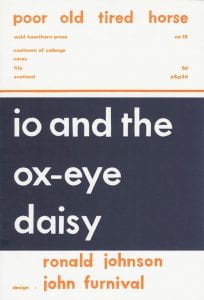

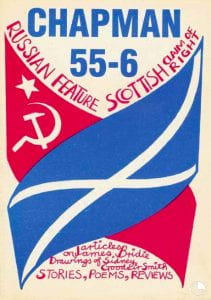

Curious to look back over this great gulf of time to the 1960s-to-1980s when I was involved, sometimes very involved, with Scottish magazines. I remember above all Alan Riddell’s Lines Review, Duncan Glen’s Akros, Ian Hamilton Finlay’s Poor. Old. Tired. Horse, Bob Tait’s Scottish International, Joy Hendry’s Chapman. Later of course it was Robin Fulton’s Lines Review.

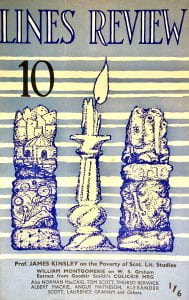

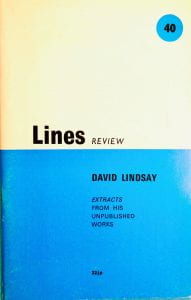

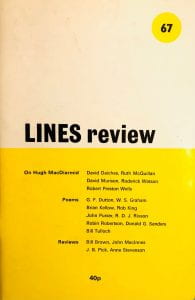

Issues of Lines Review edited (L-R) by Sydney Goodsir Smith (1955),

Robin Fulton (1972), William Montgomerie (1978), Tessa Ransford (1996)

I myself (with the help of a friend with a talent for design, Patrick Taylor) briefly edited five issues of a quarterly magazine, Extra Verse, while I was a student at Edinburgh University. I had inherited it from someone in Birmingham, and passed it on to Barry Cole in London, so it makes little showing in the annals of Scotland. But it published some good poems by Robert Garioch, Edwin Morgan, George MacBeth, George Mackay Brown, Crae Ritchie, Robin Fulton and others, not to mention an entire issue devoted to a Festschrift for Ian Hamilton Finlay.

One thing that was very striking in those days was how unpretentious many of the best Scottish writers were! I am startled, as I write out that list, that such competent and ambitious poets were willing to publish in a more or less completely invisible magazine, and it suggests an informality and friendliness that, at the time, I took for granted, but in retrospect find deeply attractive.

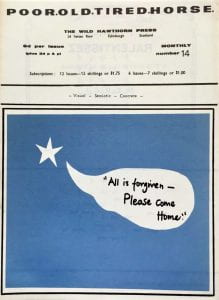

My impression is that this blog is seeking precursors for Scottish nationalism, and of course we still had the tumultuous presence of Hugh MacDiarmid to steer us in that direction. All the magazines I have mentioned were strongly biased toward “Scotland” in a cultural sense, and even I, an immigrant at the age of 8 from the British Empire, as I became acculturated in Scotland developed a prejudice against the south-east-of-England literary scene that it took many years to overcome (perhaps even now, after many years of living in London, it is still not wholly eroded). Scottish writers tended to look in every direction except England. Poor. Old. Tired. Horse, probably the most truly international of them all, published adventurous work from Austria, Iceland, France, the US… Ian Hamilton Finlay was too truly a rebel to submit to any orthodoxy, even that of Scottish nationalism; he feuded joyfully and comically with MacDiarmid, and finally established Little Sparta to celebrate his chronic war against the Athens of the North. For all that, he was profoundly Scottish and his magazine to my mind always had a lovely echo of his wonderful and insinuating accent.

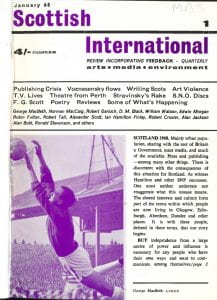

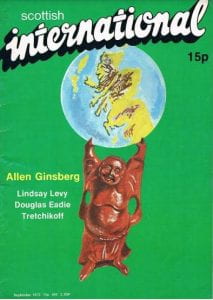

I would say, impressionistically, that things changed in the late 1960s; prior to that time, the “nationalism” was mainly cultural. We were living the Dream, in Scott Hames’s term, and the Grind had not yet begun. (Winifred Ewing’s victory at the Hamilton by-election in 1967 changed all that.) The founding of Scottish International in 1968 was an important moment. I had known Bob Tait quite well as a student (he had edited a small magazine called Feedback – appropriately green, as he remarked), and was both surprised and pleased when he suddenly shot to prominence as one of the three editors, shortly to become the main editor, of this major new initiative by the Scottish Arts Council. I was by then away from Edinburgh, either in London or living at Findhorn, and could never make sense of the political hostilities around the magazine – MacDiarmid’s hostility to the project, in particular, and also Tom Scott’s. I assume now it was because the Dream was being taken over by the Grind, and the extravagance of some of MacDiarmid’s positions – his theatrical “Stalinism”, for example – was being marginalised by the attempt of others to think realistically about ordinary political concerns.

Bob, I think, was too young to be quite able to cope with the pressures he came under. He had his own strong socialist views (he was less interested in the “Scottish tradition”, and more fascinated by the modern world – he had a great admiration for the Canadian pioneer of media studies, Marshall McLuhan), and he allowed these views increasingly to dominate the magazine, which really needed, if it was to justify its expensive Arts Council backing, to be able to stand back and give hospitality to a wider range of positions. It became more “political”, and less “literary”, and the roles of Bob’s nominal co-editors, Edwin Morgan and Robert Garioch – probably not roles in which either of those sensitive men could flourish – drifted into ineffective “adviser”-ships. In 1973 Bob was ousted, and his position was taken over briefly by Tom Buchan.

Lines, Akros, and Chapman, were all longer-lived and more clear in their focus. Lines and Akros were both predominantly literary: Lines was subsidised by the printer and publisher Callum Macdonald, and presented itself with his sobriety and simplicity (a shy, friendly man, he was also the printer of my own Extra Verse). I thought of Lines as Scotland’s “premier” poetry magazine, perhaps because it was so long-running (it had been founded in 1952) and appeared so reliably. While Robin Fulton (now Robin Fulton Macpherson) was editor, I published two collections in the Lines Review Editions series, but doubted my wisdom later as they received little publicity even within Scotland, and none at all outside it. This of course was the backside of Scottish amiability: the magazines were very hospitable to young writers, but poets who were a bit savvy about building a larger reputation, like Norman MacCaig, knew they had to find publication outside of Scotland.

I look back on Akros with particular pleasure. Duncan Glen was passionately committed to Scottish writing (and wrote well himself, in a lightly accented Scots); rather surprisingly, he lived in England, in Preston, and when I did an MA at Lancaster university I visited him there on several occasions: he was always extremely generous and supportive. I have a sense of owing him many debts, and he was willing to publish lengthy pieces, both of poetry and prose, that few magazines would have entertained. I once thanked him for publishing my very long poem ‘The Hands of Felicity’ with ‘almost miraculous accuracy’. He at once bowed out of the firing line and credited his wife, Margaret: she was Akros‘s meticulous proof-reader. Lines (under Robin Fulton), and Akros too, both had a sense of responsibility with regard to publishing reviews, and keeping abreast of new writing. This is a most important function, especially in a small country like Scotland where criticism, as a serious activity, was often sidelined in favour of partisanship (MacDiarmid too often setting the example).

Chapman, founded in 1970 by Walter Perrie and others, but edited for most of its life by Joy Hendry, probably managed best of all the tension between literature and political issues. It was unmistakably “Scottish”, but was also able to address very directly matters to do with feminism and other social and cultural issues. One issue was entitled “Woven by Women”. An issue in 1983 was headlined “The state of Scotland: the predicament of the Scottish writer”, and asked very directly what it meant, for better or worse, for a writer to be Scottish: is it “a predicament or a blessing?” It was notable that by then the tone had changed: Scottish nationalism had moved on both from the simplicities of the Dream and the obsessionality of the Grind: most contributors were thinking practically and the intermediate notion of “devolution” had entered the discussion.

I look back on all these magazines with great gratitude, for the hospitality they offered me, and also with considerable admiration, for the genuine seriousness and the high aspirations of their editors and backers. They represented both a community and a context in which excellent and characterful writers could develop, and the larger topics, to do with “Scotland” and its characteristics, could be debated. And I notice I haven’t even mentioned that witty and admirable poet, Alan Jackson, whose sardonic essay on “The Knitted Claymore” (Lines Review, 1971) introduced some welcome comedy into the conversation. The word community is what I would now emphasise: these magazines were the vehicles of a very warm and idiosyncratic community – quite a coherent national “culture”, but with no sense, to my feeling, of the gravitational pull of a political party-line.

I look back on all these magazines with great gratitude, for the hospitality they offered me, and also with considerable admiration, for the genuine seriousness and the high aspirations of their editors and backers. They represented both a community and a context in which excellent and characterful writers could develop, and the larger topics, to do with “Scotland” and its characteristics, could be debated. And I notice I haven’t even mentioned that witty and admirable poet, Alan Jackson, whose sardonic essay on “The Knitted Claymore” (Lines Review, 1971) introduced some welcome comedy into the conversation. The word community is what I would now emphasise: these magazines were the vehicles of a very warm and idiosyncratic community – quite a coherent national “culture”, but with no sense, to my feeling, of the gravitational pull of a political party-line.

D.M. Black is a Scottish writer and psychoanalyst based in London. He has published seven collections of poetry, several pamphlets, and has written extensively on poets of the Scottish Renaissance. More recently he has written about Dante in the International Journal of Psychoanalysis and Los Angeles Review of Books. His translation and commentary on Dante’s Purgatorio will appear later this year in the New York Review of Books Classics series.