Richie McCaffery on the most beguiling and enduring poetry magazine of the early 1960s.

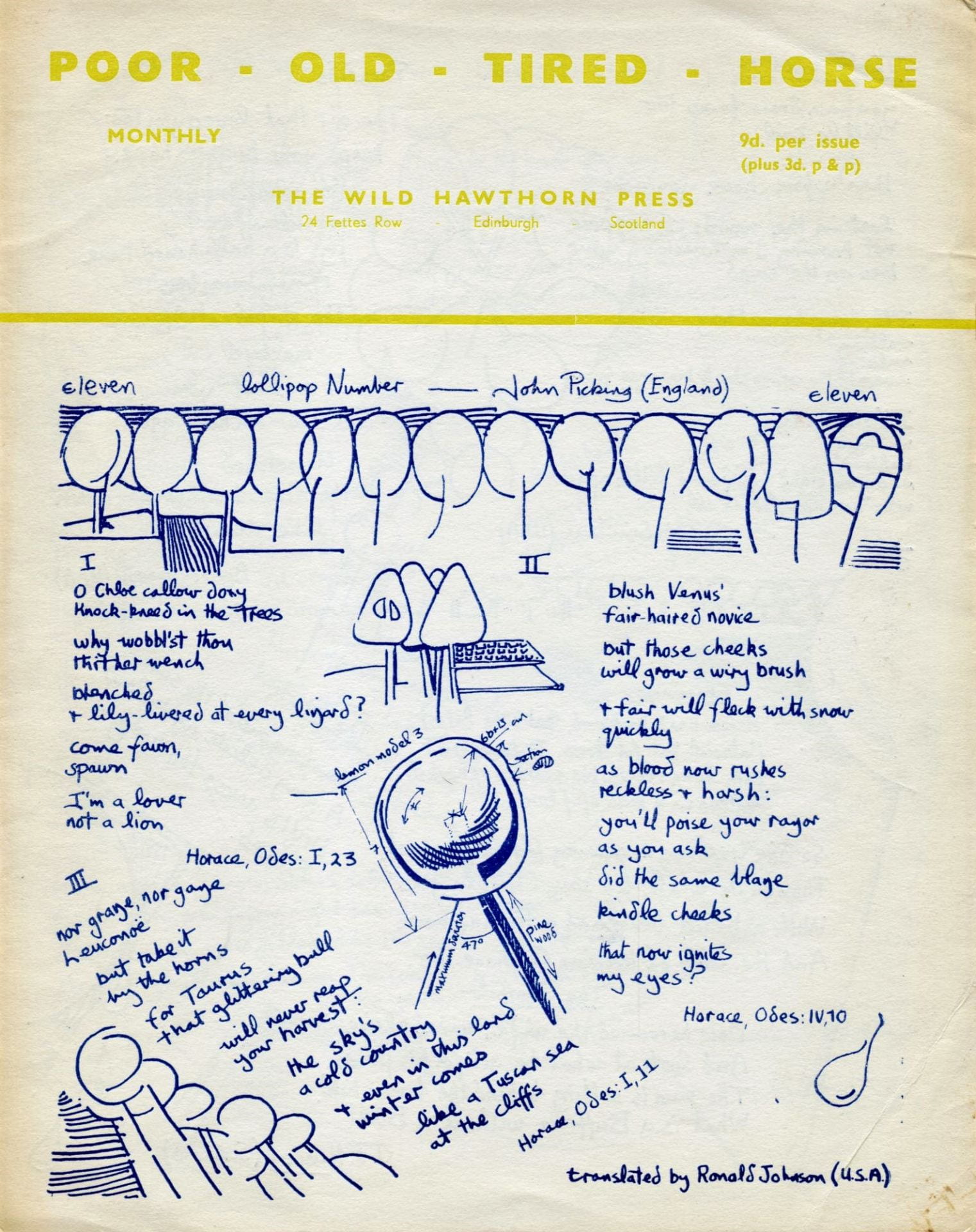

Poor. Old. Tired. Horse. (1962-7) is one of the pre-eminent international and avant-garde literary magazines of the 1960s. The creation of Scottish concrete poet Ian Hamilton Finlay (1925-2006), its fugitive lifespan belies that fact that it managed to run for 25 issues in just five years, a feat of remarkable creative industry. More than a poetry magazine, POTH was, in Mark Sladen’s words, a ‘cross-pollination of art and literature’. It is now highly collectable, and many important libraries have only incomplete sets. Its great desirability is testament to the continuing relevance of the magazine, its relatively small distribution and its comparative fragility.

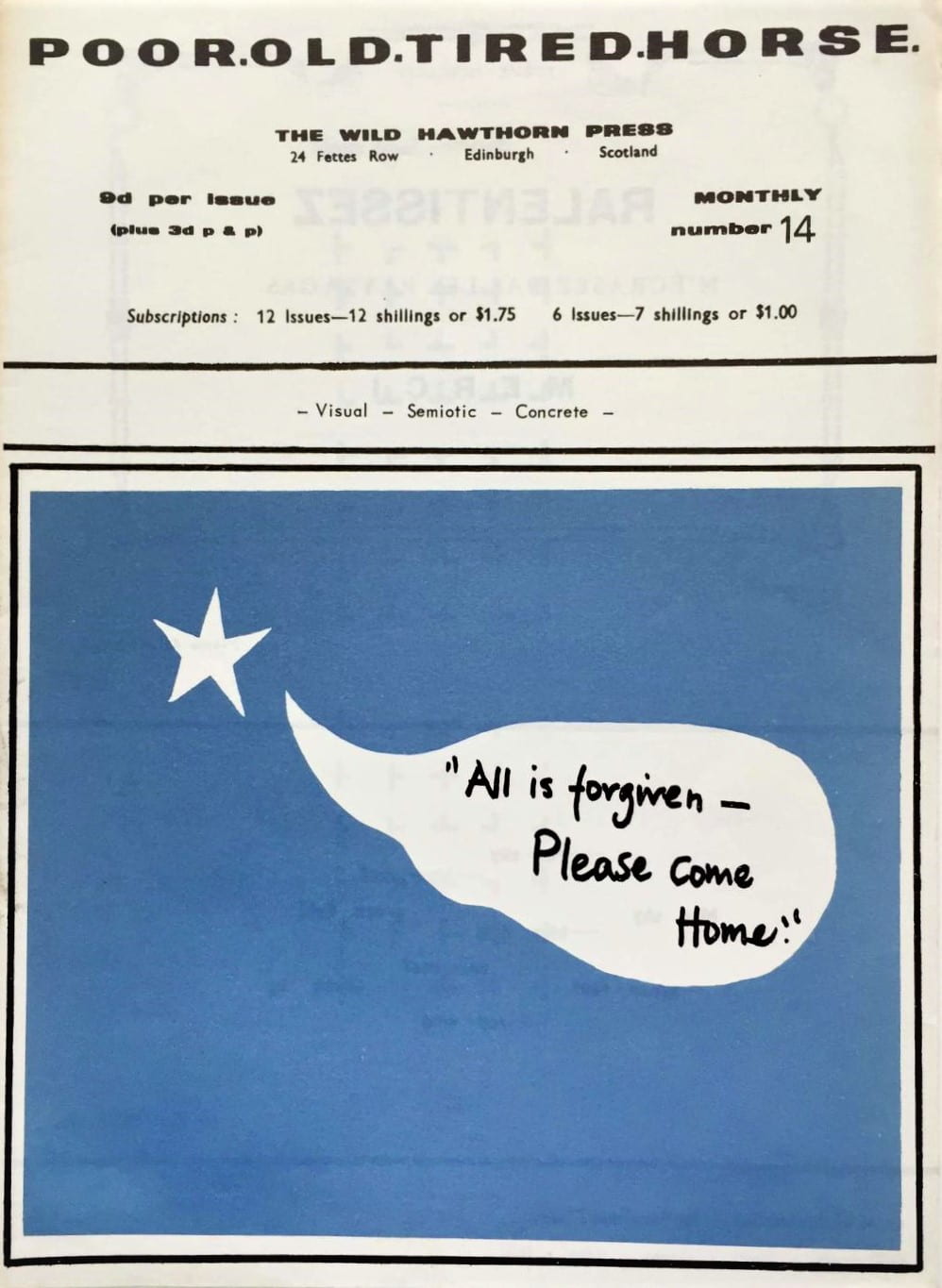

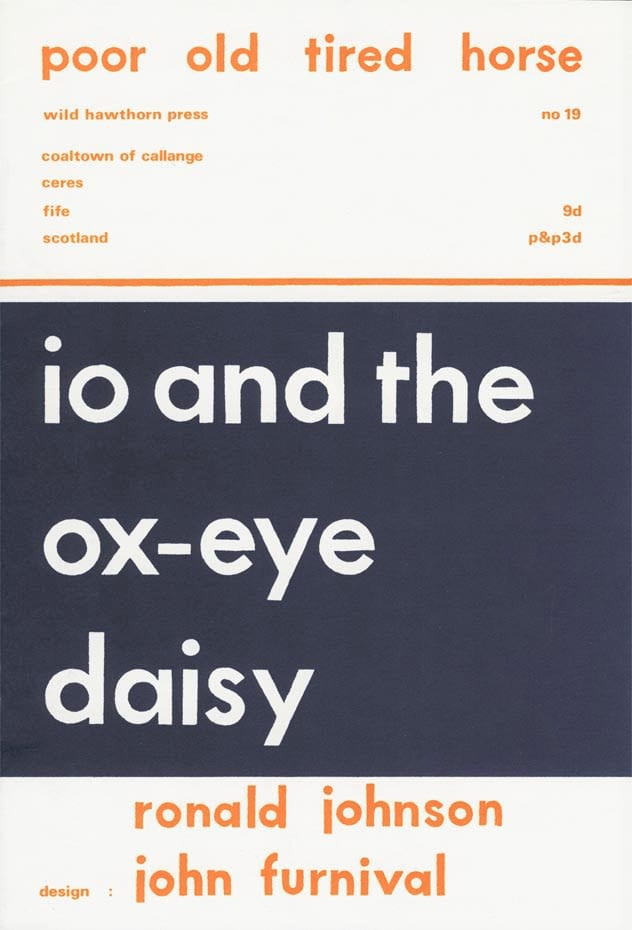

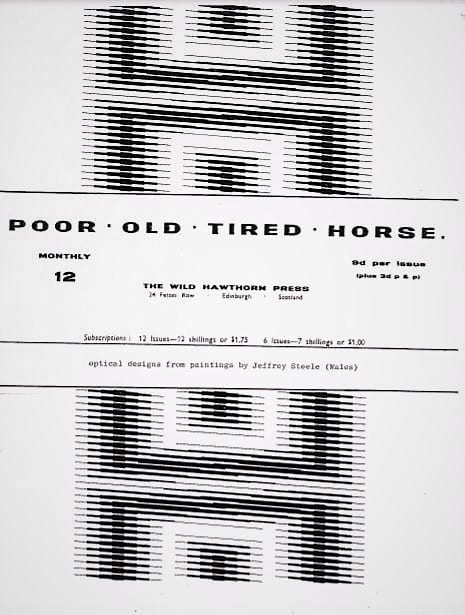

Early issues were a single sheet of paper, folded in two to give four pages of poems and illustrations, with later issues being printed on glossy paper and sometimes running to as many as twelve pages. There are no editorials – surprisingly, given the editor’s vociferous letters to friends, foes and the press. Instead, the very aesthetic of the publication and its wide-ranging roster of contributors became the manifesto. Early issues look very similar, spare and elegant, black and white with four pages of poems, later issues being visually more ambitious, the cover art changing each time.

In nearly fifteen years of book collecting, I have managed to assemble a tatty harlequin set of seven numbers of POTH. Inside my copy of issue five is a letter from Jessie McGuffie (co-founder with Finlay of the Wild Hawthorn Press in 1961) to the playwright W. Gordon Smith (1920-1996) saying that the poem ‘Poem’ on page one was ‘sent specially to us by e e cummings just before he died’. That is an amazing coup, to host the last poem published in a major poet’s lifetime. In the poem cummings imagines himself as a young boy looking out of the window at the ‘gold’ of a ‘november sunset’:

(and feeling: that if day

has to become night

this is a beautiful way)

In their study of British Poetry Magazines: 1914-2000, David Miller and Richard Price describe POTH as ‘at turns interested in sound, visual, futurist, objectivist, concrete and minimalist poetry, not to mention art and photography’. Though wholly his creation, Finlay never treated the magazine simply as a platform for his own work. The bold syncretism of POTH must have been a fillip in early 1960s Edinburgh, not to mention an irritant to more narrowly nationalist members of the Hugh MacDiarmid set. It’s clear that Finlay did not actively discriminate against members of the Scottish Renaissance, happily publishing the likes of Helen B. Cruickshank, Hamish Maclaren, George Mackay Brown and his friend Edwin Morgan (through whom Finlay was first introduced to concrete poetry). Indeed, some of his choices are quirkily traditional in such a pioneering magazine (for instance, featuring of poems by the archetypal fin-de-siecle poet Fr. John Gray in issue nine). Edwin Morgan argues that POTH was looking for ‘connections between […] different categories’ as part of a drive to ‘surprise and stimulate’. Others treated POTH as provocation.

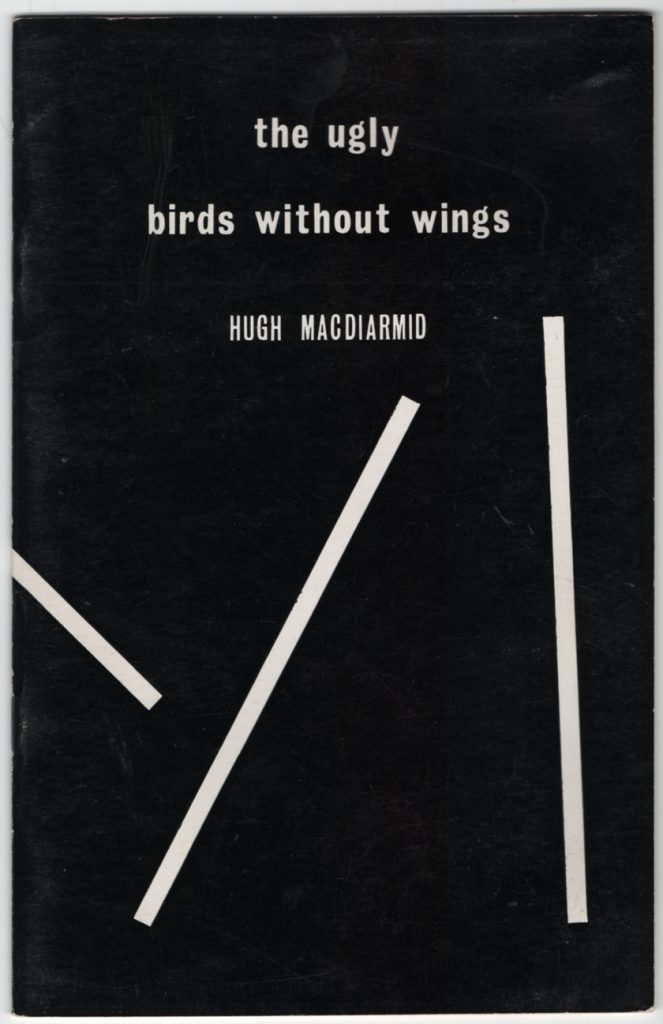

Opposition to Finlay and POTH was a minority sport fronted by MacDiarmid and his most fanatical acolytes, Sydney Goodsir Smith and Douglas Young. The main diatribe is MacDiarmid’s own pamphlet The Ugly Birds Without Wings (Allan Donaldson, 1962), published when only a few issues of POTH had appeared. It is a gratuitously mean-spirited attack on a youthful culture trying to do something novel and for themselves, dismissing them as nothing more than ‘teddyboy poetasters’ (an outdated insult even at the time).

Younger Scottish writers are disparaged as ‘the little men, the hopeless mediocrities, ganging up against their betters’ and Finlay’s Wild Hawthorn Press is deliberately mis-labelled as the ‘Wild Flounder Press’. MacDiarmid denigrates the editor and his followers as ‘jeunes refuses’ (‘recalcitrant youth’), in much the same spirit as he had attacked entrenched attitudes in his own Contemporary Scottish Studies back in 1926. Much of MacDiarmid’s argument gets sucked into irrelevant territory, muddying the waters by comparing young poets to pop singers. In truth the two poets had a good deal in common, and began as friends (MacDiarmid was best man at Finlay’s wedding). Both were fixedly taken up with ‘the global range and multiplicity of [their] own contacts with foreign writers’, in MacDiarmid’s phrase. We might even detect a faint homage to the older poet in POTH. Duncan Glen suggests that Finlay was not after praise or approval but rather wanted to shake things up – we might recall MacDiarmid’s self-description as the ‘cat-fish that vitalises the other torpid denizens of the aquarium’ – and that he ended the magazine when he became disillusioned with mainstream acceptance of concrete poetry.

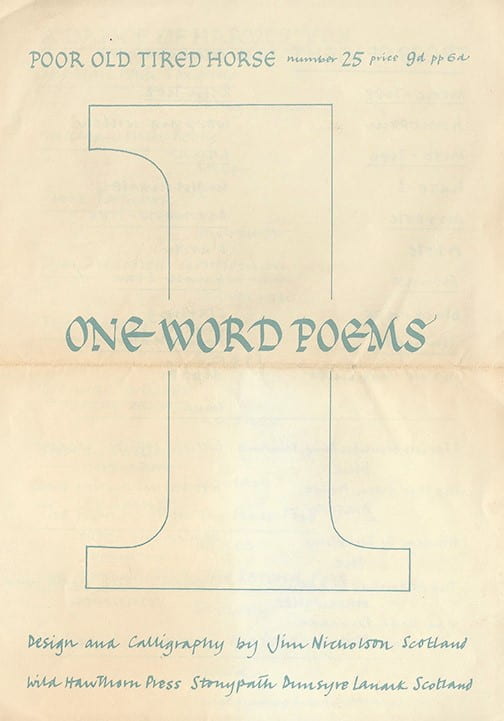

POTH put out its last issue in 1967, nearly 55 years ago. The last issue was dedicated to ‘one-word poems’ and was a masterclass in how to put emphasis on one word through a clever title:

‘The Man with Seagulls’

– Ploughman

‘The Friend of the Dove in the Doorways of Bread’

– Child

(both by George Mackay Brown)

During the evanescent course of its life POTH published a wealth of writers of international stature. There is no organ to match it in Scotland other than Alex Neish’s Sidewalk (1960) and Bill McArthur’s Cleft (1963-4) both of which died after two issues (while retailing for much more than the 9d of POTH while still appealing to students). No other journal in Scotland can boast e e cummings, Pablo Neruda, Theodore Enslin, Lorine Niedecker, Ernst Jandl and many more as willing contributors. In Edwin Morgan’s requiem for POTH (published in Wood Notes Wild) he asserted that ‘good or bad, convincing or irritating, it [POTH] will be missed’. The magazine’s title is drawn from Robert Creeley’s 1959 poem ‘Please’, itself a plea for a space for consideration:

This is a poem about a horse that got tired.

Poor. Old. Tired. Horse.

I want to go home.

I want you to go home.

So Finlay’s horse got tired in time, tired of carrying a heavy load of something outré and new. But even Creeley’s poem calls for a homecoming. Isn’t the pull of origins rather odd when you’re trying to blaze a new trail? I don’t think so. Like MacDiarmid before him, Finlay was trying to widen the scope of internationalist writers like himself, to find a home in the wide-open world.

Richie McCaffery is a poet and critic from Northumberland, who completed a PhD on Scottish poetry of World War Two at the University of Glasgow in 2016. He is the editor of Sydney Goodsir Smith, Poet: Essays on His Life and Work (Brill, 2020).