The launch issue of a magazine tends to flaunt its novelty, but the much-delayed start to this project was focused more on backstory.

The network’s first meeting (24 February 2021) began with a short talk by Patrick Collier, developing the themes of his blog post ‘Six or Seven (or so) Ways to Read a Magazine’. This was a rich tour d’horizon of the magazine in theory, unpacking the multi-voicedness, seriality and objecthood that make these artefacts what they are. What sort of critical – or uncritical – gaze is appropriate to the magazine, Collier asked, linking several milestones in periodical studies to recent ‘method wars’ in literary studies. Exploring the value of close, distant and ‘just’ reading, alongside questions of genre and materiality, this was a highly stimulating introduction to the field.

One of its pioneers, Margaret Beetham, emphasised ‘how the formal qualities of the periodical are shaped by its particular relationship to time’.[1] And the cultural work that magazines do, Collier argued, is caught up with their iterative nature. In examining specific titles we should attend to their ‘open’ and ‘closed’ qualities from issue to issue (rather than tethering a single article firmly to its date of publication). A cultural review might respond to unfolding events from a variety of perspectives, inviting readers to participate (via letters pages) and to navigate the mixed-genre text in their own way (open), but it will also construct a consistent persona, publishing schedule and implied reader across time (closed).

Commercial magazines may have a mission statement of sorts, but we take it with a pinch of salt, knowing that advertising and circulation are the foremost considerations. Non-commercial magazines, Collier noted, are in some ways easier objects for cultural historians to handle: even if they include a wide range of material and voices, they are usually led by a small group committed to ‘making its meanings stick’ rather than generating profits.

For the Scottish magazines at the centre of our interest, their typical smallness (of circulation, of dramatis personae), uncommercial aims and strength of editorial mission (often activist or avant-garde) will often lean toward the ‘closed’ pole of Beetham’s helpful rubric. At the same time, the majority of these titles are passionately engaged in ‘opening the doors’ of cultural and political change in Scotland, focused on generating new ideas, publics and connections.

And here, perhaps, is a notable feature of periodicals linked (in varying degrees) to a wider nation-building project. For many of our target titles, the implied subject and audience is ‘Scotland’, so that journals and reviews focused on Scottish poetry, Scottish feminism or Scottish constitutional change have a stable structuring interest and ‘field’ (closed) which they are actively shaping, expanding and contesting (open); all in ways that tend to naturalise the national frame they treat both as a cultural given and a prompt to action and critique.

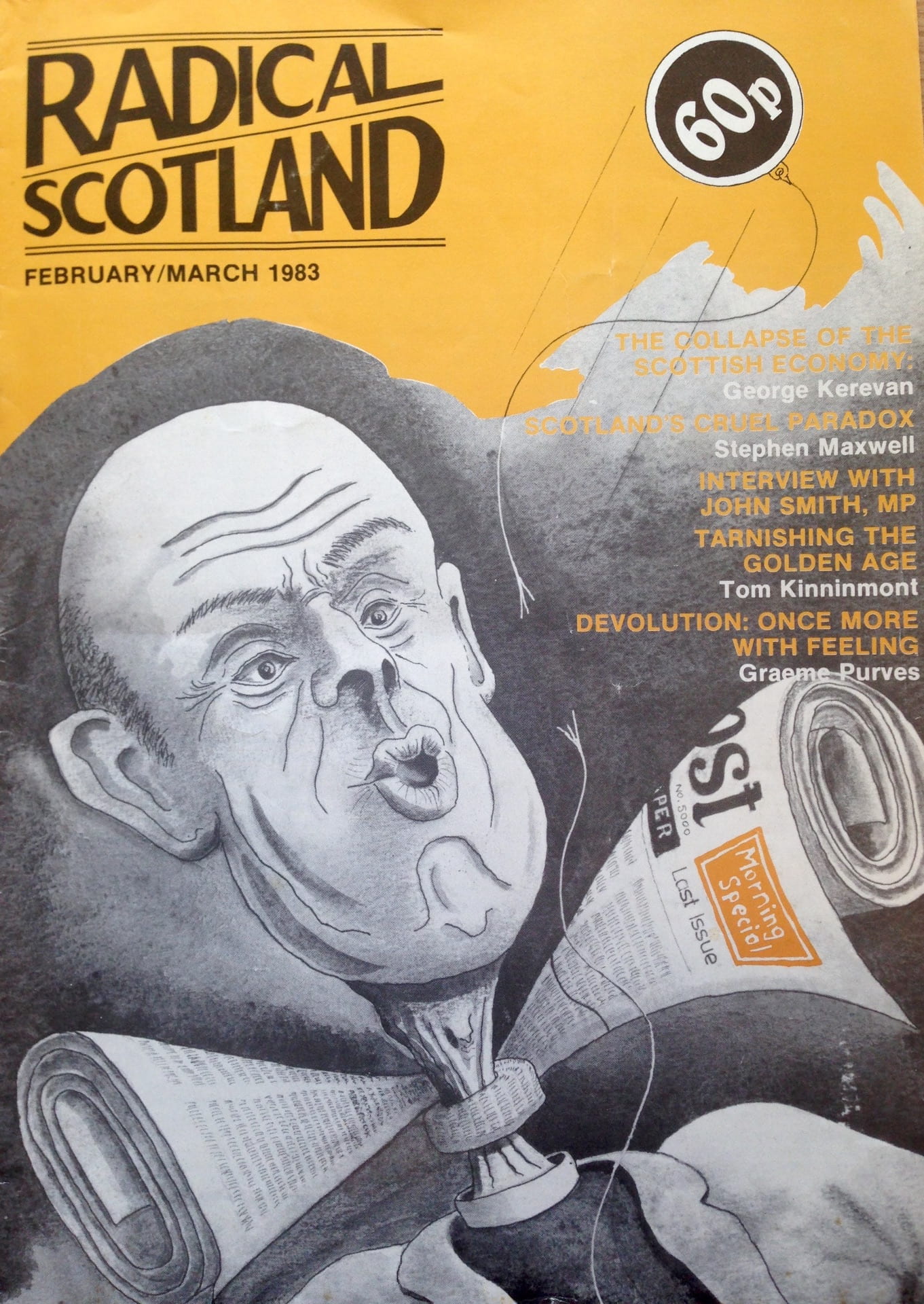

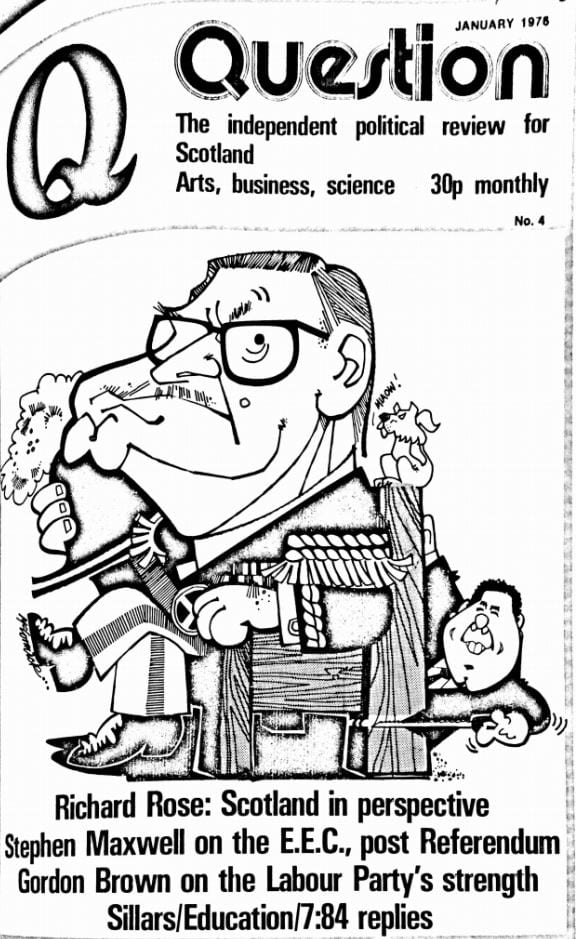

We might say that periodicals such as Question Magazine – profiled here by Ben Jackson – ‘cover’ a domain of Scottish cultural and political life they also help to ‘constitute’ and solidify, its fortnightly reports helping to make this world both discursively and materially real, available to purchase in newsagents and bookshops. One of the interesting features of these magazines is how their formally ‘closed’ features – including the notable absence of women contributors – sit alongside their more ideologically ‘open’ aims and qualities, generating fresh national possibility, community and identity.

Questions of audience are of special interest for periodicals directly engaged in politics, alliance-making and mobilisation. Rory Scothorne noted the history of revolutionary newspapers as surrogate political organisations, an often ‘closed’ and hierarchical locus of debate sharing features with the vanguardist party (and often providing a source of income for party activity). The recent work of Lucy Delap (on the print-culture of British feminism) was noted for its relevance in studying magazines as modern political and rhetorical forms, and Patrick Collier noted the broader importance of periodicals in constructing ‘counter-public spheres’.

Questions of audience are of special interest for periodicals directly engaged in politics, alliance-making and mobilisation. Rory Scothorne noted the history of revolutionary newspapers as surrogate political organisations, an often ‘closed’ and hierarchical locus of debate sharing features with the vanguardist party (and often providing a source of income for party activity). The recent work of Lucy Delap (on the print-culture of British feminism) was noted for its relevance in studying magazines as modern political and rhetorical forms, and Patrick Collier noted the broader importance of periodicals in constructing ‘counter-public spheres’.

In these ‘parallel discursive arenas’, Nancy Fraser argued, ‘members of subordinated social groups invent and circulate counterdiscourses, which in turn permit them to formulate oppositional interpretations of their identities, interests, and needs’.[2] We can readily see how this description fits many of our Scottish titles, but might also observe the paradox of conceiving the national public (real or potential) as a subaltern counter-public – a paradox much easier to glimpse after two decades of devolution and the rapid consolidation of a Scottish democratic system.

In these ‘parallel discursive arenas’, Nancy Fraser argued, ‘members of subordinated social groups invent and circulate counterdiscourses, which in turn permit them to formulate oppositional interpretations of their identities, interests, and needs’.[2] We can readily see how this description fits many of our Scottish titles, but might also observe the paradox of conceiving the national public (real or potential) as a subaltern counter-public – a paradox much easier to glimpse after two decades of devolution and the rapid consolidation of a Scottish democratic system.

Speaking from the archivist’s point of view, Graeme Hawley highlighted the practical and classificatory challenges that accompany the definitional conundrums outlined in Collier’s introduction: what exactly is a magazine, viewed in terms of its physical dimensions, publishing schedule, balance of visual and textual material, and so on? How can the dizzying variety of their content, and the embedded knowledge they ‘accidentally’ capture (e.g. the way a demolished building looked in a photograph from 1960), be tagged or catalogued for disaggregation and research, using digital finding aids? These reflections recall Beetham’s point (cited by Collier) that the magazine is ‘not so much a form in its own right as an enabling space for readers traversing the items they encounter’. How can this ‘enabling space’ be mapped for others, and made accessible to readers physically remote from archival collections? At the encouragement of the group, Hawley agreed to write a separate SMN blog developing these thoughts. The network will return to the question of digitisation later in the year.

This was a rich and dynamic conversation I can’t fully summarise, but here are a few points and observations that lodged in my memory:

-

-

-

- Ben Jackson was the first of several (including the author of this blogpost) to confess having used magazine articles as ‘disaggregated’ historical fodder, rather than (as Collier suggested) ‘reading magazines closely as magazines’. Collier noted the inevitability of selectivity in using magazines for teaching or research, and offered generous absolution.

-

- Reflecting on her own time with the Cencrastus editorial collective, Glenda Norquay complicated the image of politically driven magazines as ‘closed’ organisations. Although there may be an agreed editorial agenda, the nature of such magazines demands unpaid work at different levels and also a turnover of editorial staff, which can produce a degree of instability. An unchanging masthead can also conceal multiple perspective and evolving internal views.

-

- Charlotte Lauder pointed out that mass-circulation commercial magazines can also have strong viewpoints, and directed our attention to publishers and proprietors (not only editors and contributors) in studying these agendas. Charlotte’s own work on The People’s Friend, owned and published by the Liberal MP for Dundee John Leng prior to its sale to DC Thomson, is a fascinating example.

-

- Alex Thomson noted the importance of state patronage and public subsidy, especially via the Scottish Arts Council. In addition to their own strong agendas, most of our Scottish magazines would also face the imperative of satisfying the funding body (within a distinctive ‘double arm’s length’ regime prior to devolution, enjoying greater autonomy from government). This support was often premised on the publication of original literary content (poetry and short stories), effectively cross-subsidising these magazines’ more contentious offerings (for which the SAC was not paying and was not strictly answerable).

-

- Malcolm Petrie noted the ‘interlinked’ nature of these Scottish magazines, and the many lines of affiliation (and occasional discord) by which they were knitted together. How might we approach them as a collection of titles, instead of separate entities? Patrick Collier observed that magazines always exist in dialogue with each other, and suggested framing our research agenda in a way that spotlights the threads of debate between magazines, thus foregrounding the broader ‘ecology’ in which they interact.

-

- Nikki Simpson noted some of the practical challenges and potential of archiving magazines, and outlined her own plans to establish an International Magazines Centre in Edinburgh. The special challenges of copyright for digitisation will be a key focus of the network in later events.

We rounded off the meeting with some planning discussion relating to upcoming activity (events, podcasts, interviews), and further details of the edited book project in development. The editors will be commissioning chapters later this year, with a preference for cross-disciplinary perspectives and co-authorship of chapters. Further details and a call for papers will follow soon.

This much-delayed start to the network’s activity was truly heartening, and we look forward to our next meeting. Prompted by Patrick Collier’s short bibliographic tour of periodical studies, we thought it might be helpful to compile a mini-bibliography on the Scottish contexts of our target magazines.

-

-

[1] Margaret Beetham, ‘Open and Closed: The Periodical as a Publishing Genre’, Victorian Periodicals Review 22.3 (Fall, 1989): 96-100 (p. 97).

[2] Nancy Fraser, ‘Rethinking the Public Sphere: A Contribution to the Critique of Actually Existing Democracy’, Social Text 25/26 (1990): 56-80 (p. 67).

-