Our third event, held 24 June, was entitled ‘Future Issues: Digitising Twentieth-Century Magazines’.

This was a wide-ranging exploration of the why and how of digitising periodicals, including opportunities for co-production of digital resources with ‘memory institutions’ such as libraries and archives. We also examined the challenge posed by post-Brexit copyright law, and a compelling – indeed, heart-wrenching – case study of its practical impact for magazine studies, reviewing the British Library’s major digitisation project on Spare Rib (2013-21).

Our first speaker, Professor Lorna M. Hughes, offered a valuable tour d’horizon of recent digitisation practice, from basic ‘digital photocopying’ (simply giving access to an online repository of scanned pages) to more enriched approaches offering ‘added value’ (to researchers, to the public, to specific user-communities). Professor Hughes emphasised models of co-production and ‘slow digitisation’ which treat the move online as a process of discovery, connection-making and knowledge creation, allowing new questions and ways of reading to emerge along the way. In this perspective, the tasks of forming the digital resource (e.g. identifying rights holders, checking and authoring metadata, developing user tools for analysis) become an active, creative, experimental part of the research process itself. This approach both requires and exploits sustained engagement with complementary materials (e.g. linking digitised magazines to contemporaneous newspaper collections), and deepens relationships between researchers, copyright holders and archivists in a paradigm of ‘co-curation’.

In illustrating these possibilities – which are rarely utilised to the full in magazine digitisation – Professor Hughes touched on a range of relevant projects and platforms, operating within various legal frameworks (US, EU, UK, ??).

-

-

- Google Magazines collection

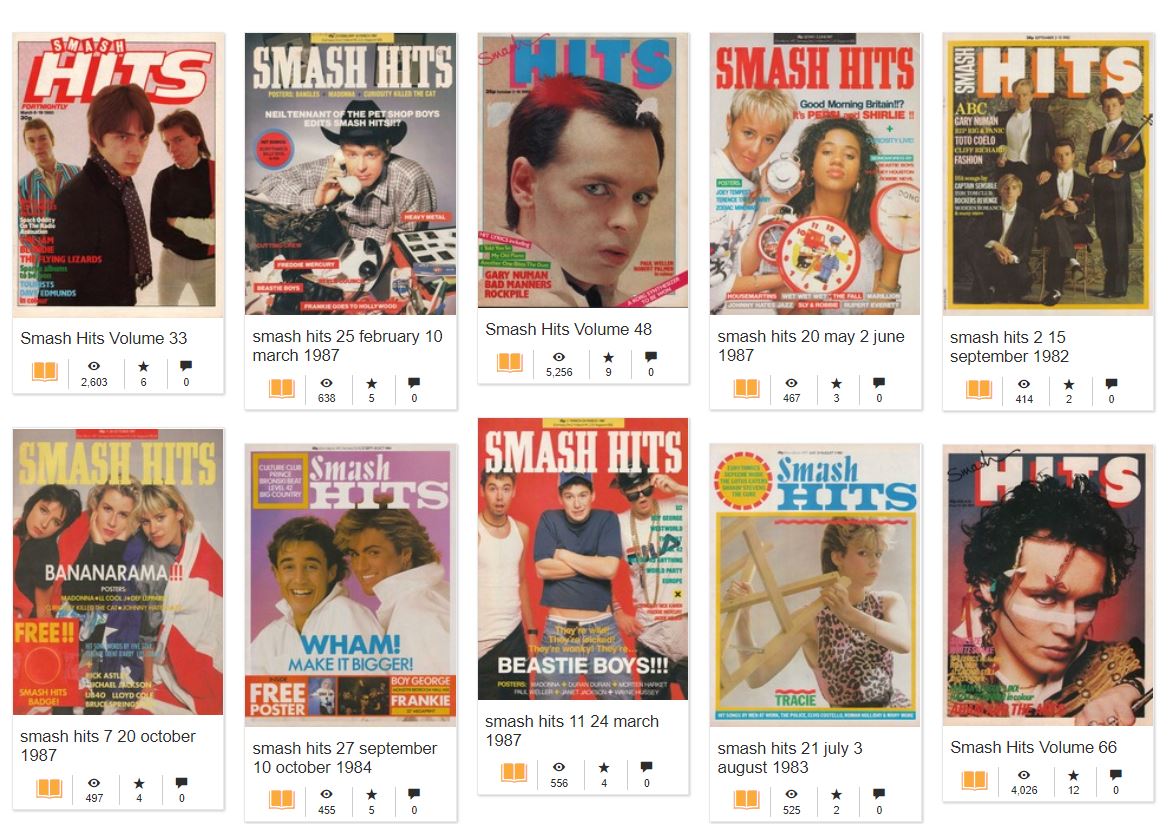

- Internet Archive Magazine Rack – e.g. Smash Hits

- Illustrated Magazines of the Weimar Republic (Arthistoricum.net)

- Welsh Journals online (National Library of Wales)

- Media History Digital Library

-

Instead of seeing digital collections as ‘destinations’ – where digitised content is created in a top-down way and ‘pushed out to users’ – Professor Hughes invited us to view digitation ‘as a journey of creation that brings lots of disparate experts into the conversation’, both uncovering and generating new scholarly possibilities.

This was an inspiring account of the varied purposes and potentials of digitisation, but tempered by awareness of the time, labour and resources required to go beyond digital photocopying. (The term ‘slow digitisation’ tells its own story: one involving hands-on openness to the unplanned and unfunded.) Our next speaker was Fredric Saunderson, Rights and Information Manager at the National Library of Scotland. He gave a lucid introduction to another constraining factor in digitisation – that of copyright law – while highlighting some possibilities amid the prohibitions.

After a crash-course on the essentials of copyright, Saunderson explained the two main paths for re-use of in-copyright works (such as the post-1960s magazines on which this project is focused): seeking permission from all copyright holders, or utilising legal exceptions to copyright (allowances defined and limited in law, with no permission required).

Libraries and archives have special affordances in UK law, and may create digital copies of in-copyright works for preservation purposes, ‘for text and data analysis for non-commercial research’, and on several other grounds (e.g. disability access). There are intriguing possibilities in this area – for text and data mining, for onsite access to preservation copies – but also strict controls. In navigating this terrain, Saunderson helpfully emphasised the key legal difference between a) digitising material and b) making use of digitised material (where, for what purpose, how?). It’s the latter that defines the viability of a digital resource within this legal framework.

Where does this leave our aspirations to digitise post-1960s Scottish magazines? At the genesis of this research network, there was cautious optimism that the key legal provision relevant to in-copyright magazines (and indeed all mass digitisation of in-copyright cultural heritage in Europe), the EU Orphan Works Exception (OWE) introduced in 2012, would remain part of UK law after withdrawal from the European Union.[1] That’s not how things turned out, and the OWE was repealed from UK law effective January 2021.

The impact of this change was vividly illustrated by our final speaker, Dr Polly Russell of the British Library, who led the Library’s massive Spare Rib digitisation project (2013-21). Spare Rib was a leading British feminist magazine active from 1972 to 1993, and the digitisation emerged from the BL’s Sisterhood & After project, an oral history of the Women’s Liberation Movement. Building on clear public interest in the magazine and its legacy, the Spare Rib digitisation was aimed at researchers seeking a full searchable archive, but also a more general audience of teachers, students and interested members of the public.

Dr Russell gave us a detailed overview of the project’s evolution – from scoping the resource, consulting with founding members of the magazine collective, developing a suitable archive platform (via Jisc Journal Archives), photographing magazines and authoring metadata – and legal developments which sadly required the closure of the digital resource earlier this year.

Of particular interest were the project’s struggles with copyright clearance, despite the formidable resources of the BL, significant volunteer labour, and the affordances – at the time, new and untested affordances – of the OWE. The nature of periodicals multiplied the legal and practical challenges at issue: each issue of Spare Rib included a wide variety of content, such as photographs, poems and commissioned essays, with up to eight copyright holders on a single page. Much of this content was produced by ordinary women who were very challenging to identify and locate for copyright purposes.[2]

In the initial stage of copyright clearance, a small army of volunteers sampled 20% of the magazine’s full run, in which they identified 1400 copyright holders. The team successfully contacted 400 of these individuals, with only two requesting that their material be redacted from the digital resource. On the basis of this very low rate of redaction (0.5%), the Library went ahead with digitising the full magazine, and identified a further 4500 copyright holders to contact (seeking permission) or add to the EU’s orphan works database. After the digital archive’s initial launch in 2015, organisations representing the rights of copyright holders raised concerns about some content classified as orphan, and a second process of copyright clearance resulted in redaction of 30% of the resource (around 1000 items), which the Library agreed could not be proven to fall within the OWE. After Brexit, the OWE itself was repealed – the legal basis for clearing around 80% of items in the collection – and the resource had to be taken down.

The scale, value and richness of the Spare Rib archive make the story of its rise and fall truly poignant. It is little short of tragic that the full-run archive is no longer available, but note that the BL’s curated learning site on Spare Rib is still available, including 300 items of (non-orphan) cleared content from the magazine, over 20 high-quality contextual articles, photographs, maps visualising networks of second-wave feminist activity across the UK (based on Spare Rib group and event listings), and links to oral histories. To highlight one example, this excellent primer on the 60s underground press by Marsha Rowe is of direct relevance to several SMN titles.

Dr Russell closed with some lessons learned during the project, including evidence of growing public demand for in-copyright periodical material, the need for clear policy on redaction and takedown, and that copyright clearance – even within the affordances of the OWE, now withdrawn – can be very expensive and time-consuming.

This was a sobering (and sometimes jaw-dropping) case-study, which gives the network a great deal to think about in regard to our own plans and objectives. In subsequent discussion, Graeme Hawley and Lorna Hughes discussed the importance of active engagement with copyright holders, which can become a valuable part of the process, drawing people into the project and letting them become stakeholders (and future audiences) in ways that enrich and expand the collection. Several members of the network expressed interest in ‘slow digitisation’ along these lines, creating enhanced digital collections focused on a more manageable subset of material – over which online audiences can ‘linger’ – rather than a full archive. But there are clear trade-offs here, in moving away from a searchable resource (e.g. of a magazine’s full run) that would permit large-scale analysis, comparison, text-mining and the more innovative sorts of periodical research Clifford Wulfman associates with the truly ‘digital library’.[3]

This was a hugely useful and stimulating exploration of the terrain, and its obstacles, which the network will spend some time digesting before we consider our own next steps in regard to digitisation. Our deep thanks to all the speakers.

With thanks to Alice Piotrowska, and her notes!

[1] Though its repeal from UK law creates significant obstacles for digitisation projects – and resulted in the takedown of the BL’s Spare Rib project – the EU Orphan Works Exception (OWE) is no panacea. For a concise outline of its limitations, see James Boyle, ‘(When) Is Copyright Reform Possible? Lessons from the Hargreaves Review’ (2015), section IIc: ‘In brief, the scheme is heavily institutional, statist, and inflexible. Its provisions can really only be used by educational and cultural heritage institutions, only for non-profit purposes, with lengthy and costly licensing provisions designed to protect the monetary interests of – almost certainly – non-existent rights holders. The EU seemed never to grasp the idea that citizens also need to have access to orphan works, for uses that almost certainly present no threat to any living rights holder.’

[2] Note that the OWE still required an extensive ‘diligent search’ to trace copyright holders. A work only becomes ‘orphan’ – and eligible for the associated exception or licensing scheme – when ‘it is established that the owner of the copyright cannot be identified, or if identified cannot be located’. (NB the UK’s own orphan works licensing scheme still operates, but the EU-wide OWE scheme enabled by the 2012 Orphan Works Directive has been repealed from UK law, creating risks of infringement for UK projects constructed within this framework.)

[3] ‘But what happens if you encode metadata directly into the texts themselves? If, for example, you mark up the structure of complex publications, like magazines, you can pose and answer interesting contextual questions. Let’s say you had a textbase of structured transcriptions of magazines that distinguished among pages and blocks of advertising and content. You might then be able to pose this sort of question: how many short stories by Faulkner and Hemingway were printed alongside ads for sporting goods?’ Clifford Wulfman, ‘The Rise and Fall of Periodical Studies’, Journal of Modern Periodical Studies 8.2 (2017): 226-41 (p. 234).