Rachael Alexander and Charlotte Lauder on the blind-spots and possibilities of researching feminist print

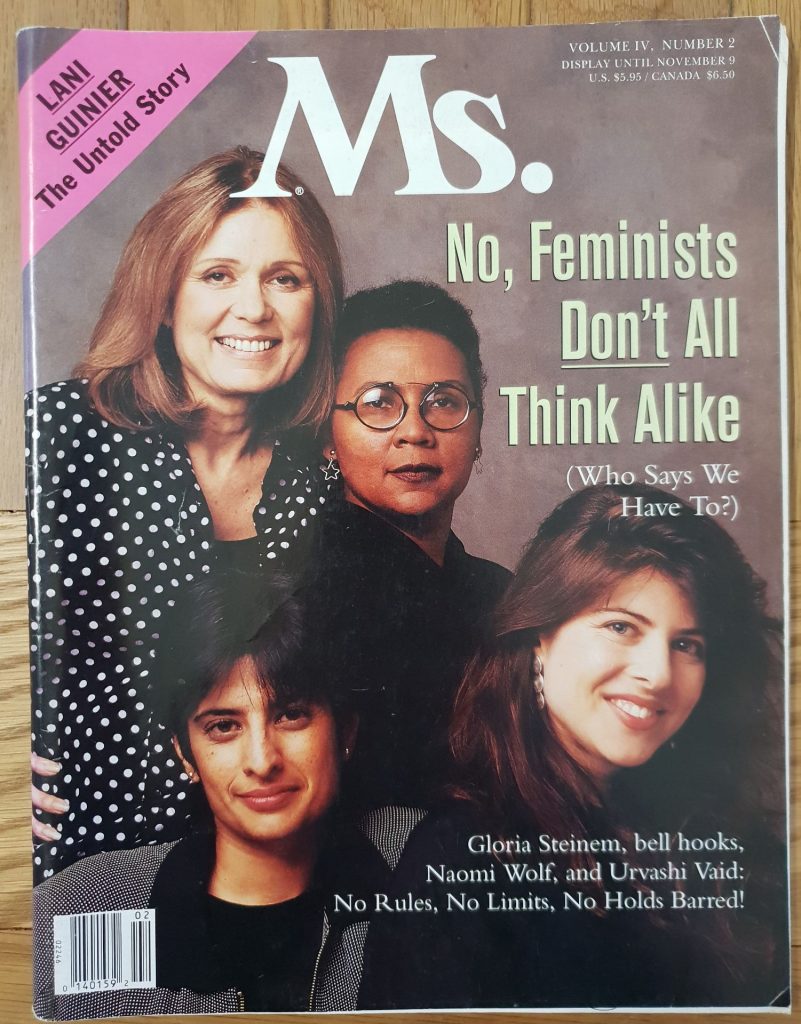

Interest in feminist magazines is on the rise. From projects grounded in academia, like the British Library’s digitised archive of Spare Rib magazine, to representations in popular culture, like Ms. magazine in the TV series Mrs. America (2020), feminist magazines have arguably never been more visible. Yet in our research, we have been struck by the lack of sustained attention to Scottish feminist magazines and periodicals. Aside from some valuable mentions, in particular from Esther Breitenbach and Sarah Brown, they seem to have been largely overlooked. In this blog post, we look to question some of the reasons for this seeming absence of interest.

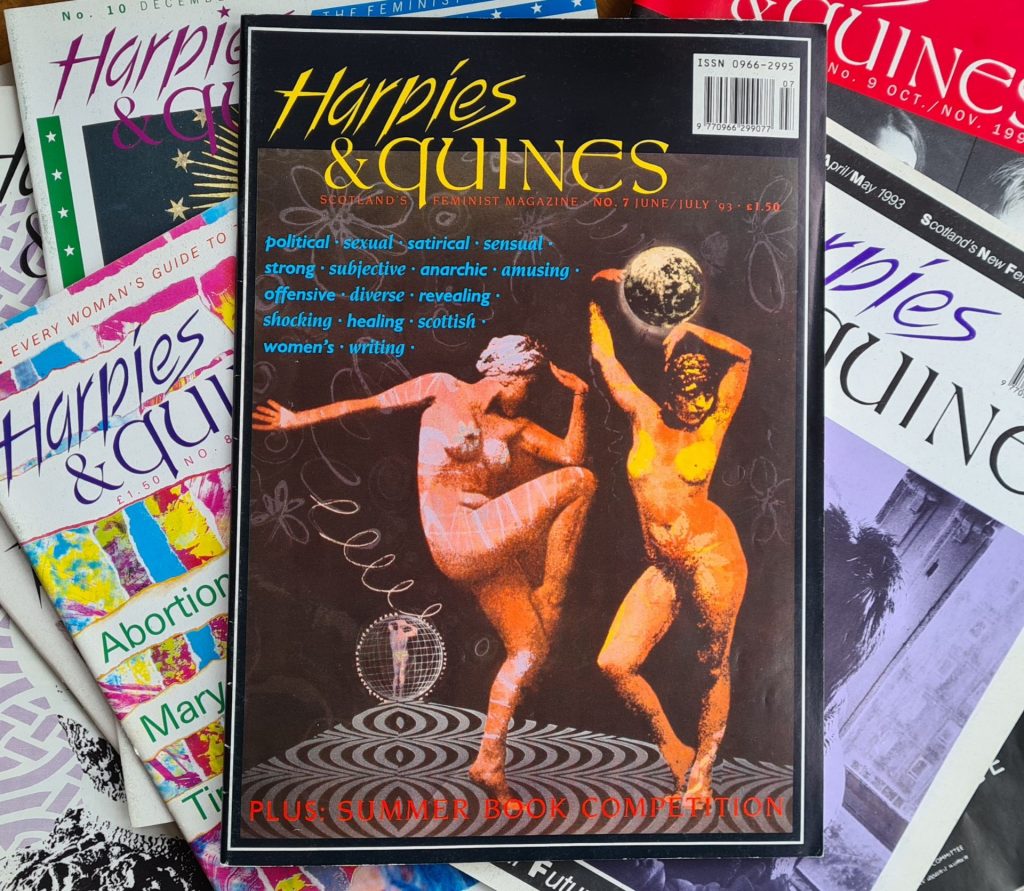

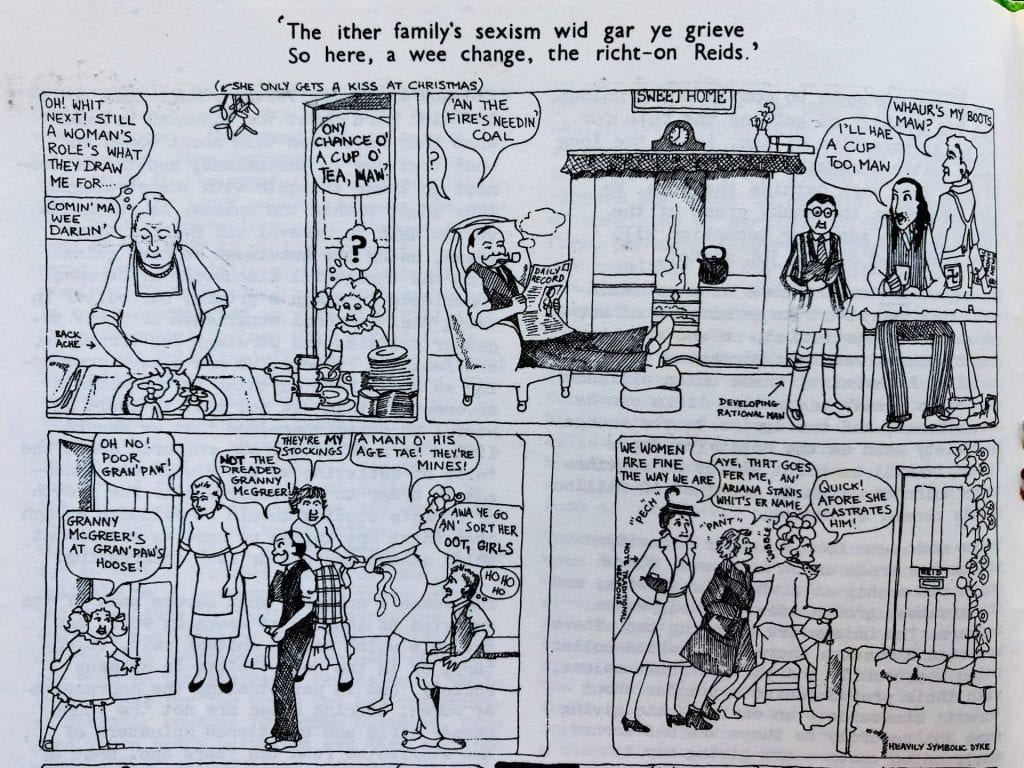

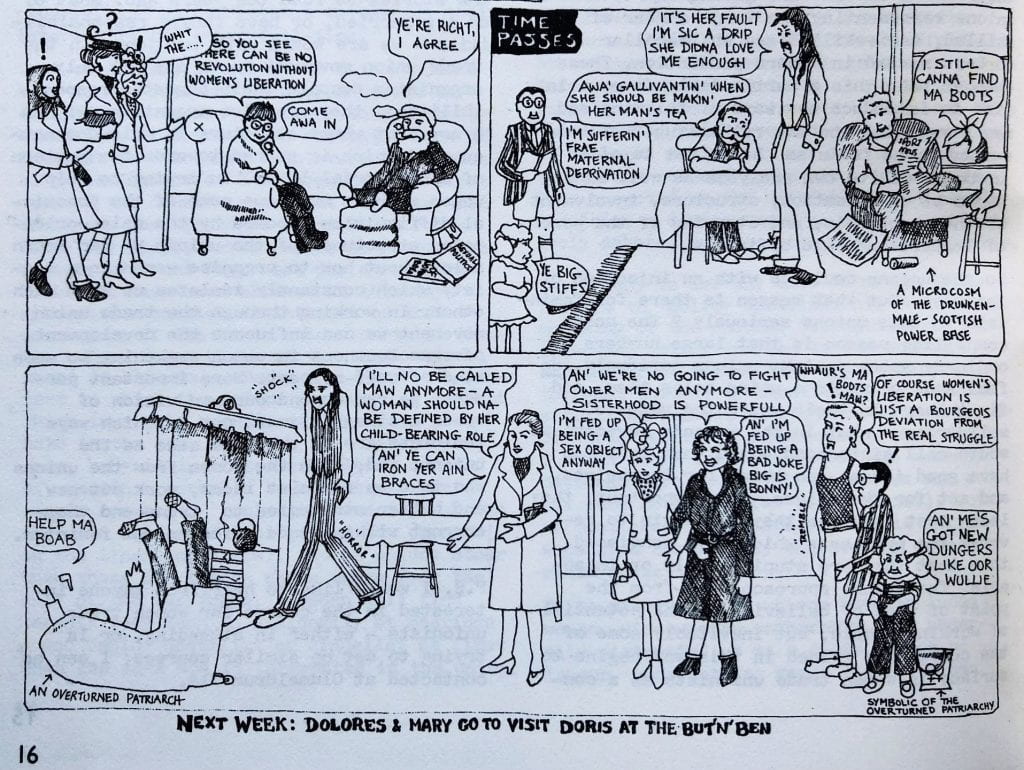

In our earlier blog, we looked at Scottish Women’s Liberation Journal and Msprint and the 1970s–80s, and here we’ll think a little more about Harpies & Quines and the 1990s. Harpies & Quines was established in 1992 and, while short-lived, it is a fascinating title. We’ll consider why Harpies & Quines – like other Scottish feminist magazines – has been overlooked, and what it can contribute our understandings of the Scottish publishing landscape and feminist publishing more broadly.

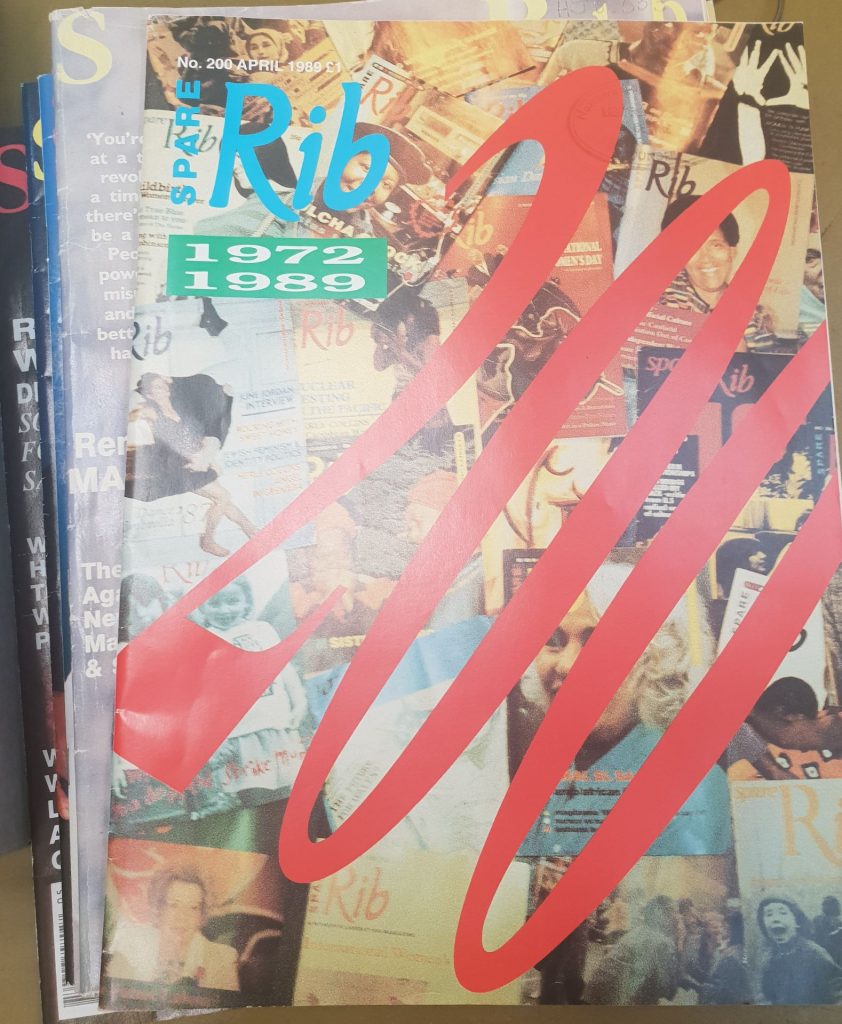

Perhaps we should begin with an acknowledgement that some (or, more accurately, many) magazines will most likely always be overlooked. Scholars working in the broad field of periodical studies frequently confront the fact that issues, titles, and whole genres must be left out – given the vast quantity of magazine material and the sheer scale of the archive. For example, in his introduction to the Routledge Companion to the British and North American Literary Magazine (2022), Tim Lanzendörfer includes a final section titled ‘The essays not in this volume’ as a way ‘to briefly acknowledge […] this Companion’s limitations’ (5). Maybe, like the magazines Lanzendörfer lists, Scottish feminist magazines have simply been left on the side-line. But this seems surprising, particularly when we consider the aforementioned attention being dedicated to feminist magazines from elsewhere, like Spare Rib and Ms.

Of course, Spare Rib and Ms. were bigger publications in almost every respect. Being aimed at British and American women, respectively, they addressed a far larger readership than Harpies & Quines, for example. Harpies & Quines also had far less funding; it was started in 1992 with subscriptions, donations, a small Community Enterprise Strathclyde grant, and £3,000 from Lesley Riddoch’s mother, Helen Riddoch. Ms., on the other hand, had $20,000 of seed money from Katherine Graham of the Washington Post and by 1972 Warner Communications invested $1 million into the magazine.[1] Spare Rib started with £2,500, a fact noted in their 20th anniversary issue, published in July 1992. (£2,500 in 1972 would be worth roughly ten times that sum today.) In that same issue, the collective commented that ‘To launch a magazine like Spare Rib from scratch in 1992 would cost at least £500,000.’ These disparities in financing have a clear impact on the materiality of the magazines; the size, the number of features and articles, and the paper quality, which have perhaps made them more attractive objects of study and attention. Ms. and Spare Rib also had significantly longer lives than Harpies & Quines, a fact not unconnected from their greater financing. Spare Rib ran from 1972 to 1993 and Ms. from 1971 with an incarnation still in print today, while Harpies lasted only two years. But we only need to look at the significant academic attention dedicated to modernist little magazines of the 1920s – characterised by tiny circulations and brief publication periods – to see that circulation and longevity do not directly correlate with levels of interest.[2]

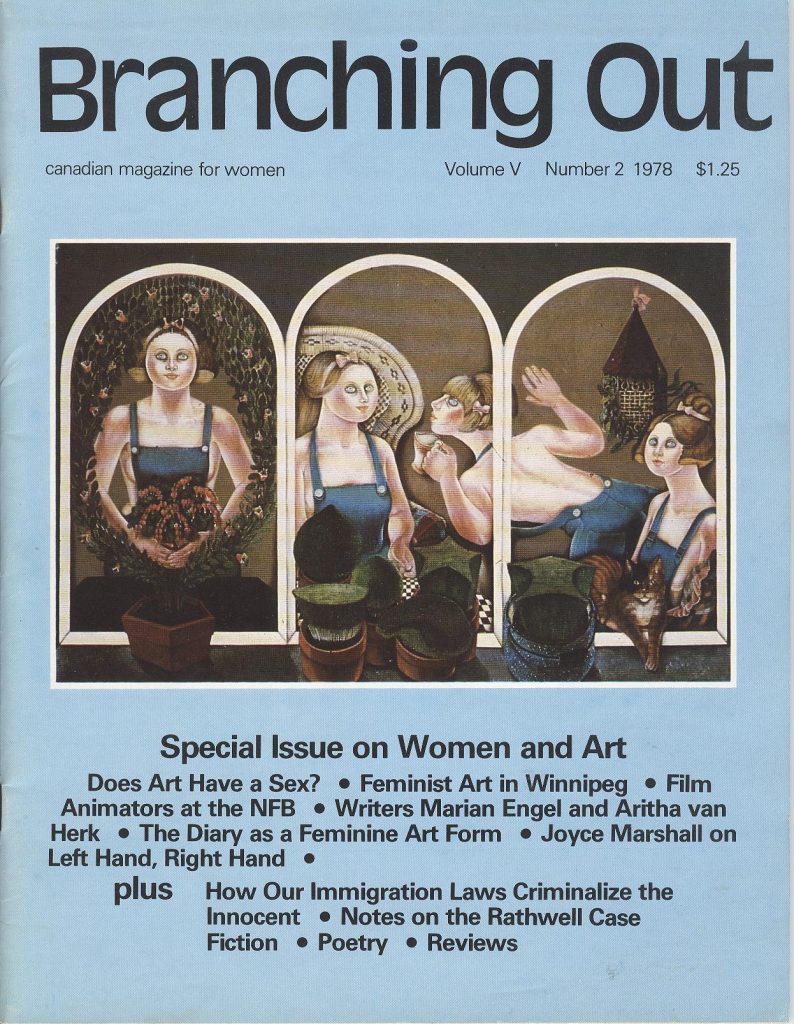

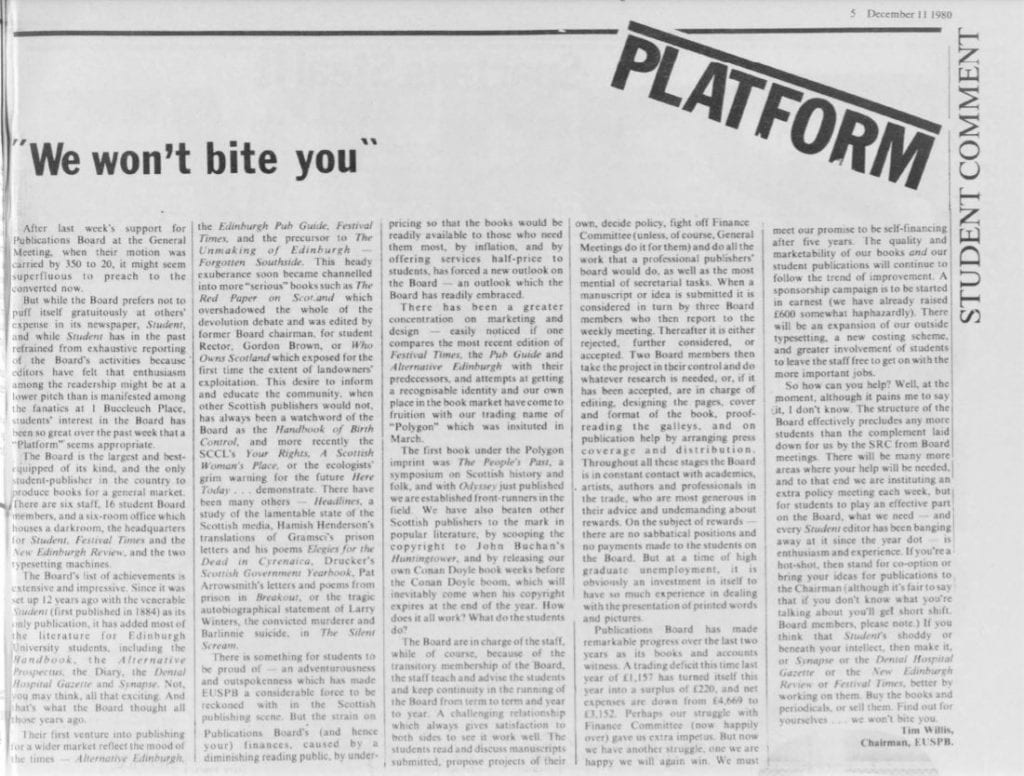

Scottish feminist magazines are by no means the only overlooked English language feminist magazines of the 1960s to 1990s that are gradually gaining attention.[3] In her recent book on the Canadian Branching Out (1973-1980) – Feminist Acts: Branching Out Magazine and the Making of Canadian Feminism (2019) – Tessa Jordan notes that the magazine had ‘completely fallen out of the historical record’ (xxix).[4] Indeed, many of Jordan’s comments on the aims and objectives of Branching Out bear resemblance to those of Harpies & Quines. Jordan notes the collective’s commitment ‘to producing a national magazine that challenged not only the male-dominated mainstream press but also American cultural imperialism’ (xx). Harpies & Quines did not, it likely goes without saying, seek to challenge American cultural imperialism. But the collective did position themselves against the macho Scottish media scene and the London-centric publishing sphere.

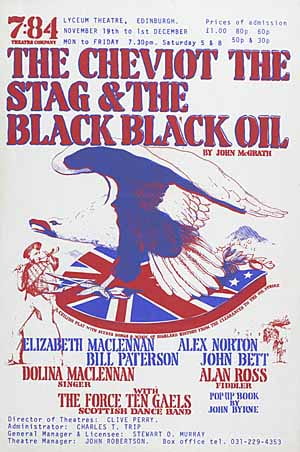

The methods used by the Harpies collective, however, diverged somewhat from Branching Out. It set itself against the daily and weekly Scottish newspapers in its emphasis on women’s writing, like all feminist magazines, but also frequently lampooned (mostly) male journalists in regular features like ‘Wanker of the Month’. It also positioned itself against conventional women’s magazines in tongue-in-cheek features like ‘How to Read Cosmopolitan and Still be a Feminist’ (December 1993/January 1994, 26). And it emphasised throughout a particularly Scottish focus, combining its feminism with constructions of Scottish identity. And again against south-of-the-border publications like Spare Rib, by arguing they were of minimal relevance ‘for anyone living north of the Watford gap’. These characteristics and how Harpies & Quines, and Scottish feminist magazines more broadly, carved out a space in the publishing landscape are a particularly aspect of interest for us in our research. Indeed, we argue that this is one of the reasons why growing attention to them is long overdue and one of many ways in which they have much to tell us about Scottish periodical culture.

We want to pause here to consider one additional reason for the relative lack of attention to these magazines: the challenges of conducting research on cultural artefacts and publishing ventures which are well remembered and often held dear by those involved in their creation. This can be a daunting prospect and raises ethical questions and considerations that do not come into the frame when considering, say, a magazine published in the early twentieth century. The magazines we focus on were produced in living memory – like Ms. and Spare Rib. But Scottish feminist magazines have comparatively little in the way of archival records. Therefore, there is a significant reliance on approaches drawn from oral history, meaning researchers rely heavily on producers and readers who are willing to talk to them. As has been well-documented by feminist oral historians, this is not only a practical challenge but a significant responsibility. But the value of these perspectives, the opportunity to speak to those involved in the production of these titles or the readers who engaged with them has been thoroughly demonstrated. Feminist oral history projects like the ground-breaking Sisterhood and After project, led by Margaretta Jolly with the archive held at the British Library, show what can be gained from such work and provide a valuable blueprint for future research.

In our conversations with a few of the women who have contributed to Scottish feminist magazines – like Esther Breitenbach, Lesley Riddoch and Libby Brooks – we’ve seen how much these magazines meant and still mean to the women involved.[5] But we’ve also gained a sense of how little we know about these titles and their origins, and how the material that exists in the pages of the magazines only tells part of what these publications meant for feminism in Scotland in the 1970s to 1990s. In continuing our research, we hope to deepen our understanding of these magazines, the collectives that produced them, and their place in the broader publishing and print culture.

Dr Rachael Alexander is based at the University of Strathclyde and is the author of Imagining Gender, Nation and Consumerism in Magazines of the 1920s (2021). Her research focuses on constructions of gender in twentieth-century periodicals and print cultures, in Scotland, Britain, the US, Canada and Scotland.

Charlotte Lauder is a PhD student at the University of Strathclyde and National Library of Scotland researching Scottish magazine culture from 1870 to 1920. Her work on Scottish women’s magazines has been featured on BBC Radio Scotland.

Notes

[1] Amy Erdman Farrell provides an excellent summary of this in her book Yours in Sisterhood (1990).

[2] There are many fantastic books on little magazines, such as Mark S. Morrisson’s The Public Face of Modernism (2001) and Eric Boulson’s Little Magazine, World Form (2016), and broader digitisation projects, such as the Modernist Journals Project (modjourn.org).

[3] We add the caveat of English language here, in keeping with Lanzendörfer’s candour, to acknowledge the limitations of our own research.

[4] Some digitised issues of Branching Out can be found at the Rise Up! feminist archive: https://riseupfeministarchive.ca/publications/branching-out/

[5] You can listen to our discussion with Esther Breitenbach here: https://campuspress.stir.ac.uk/scotmagsnet/2021/04/16/podcast-esther-breitenbach/