Magazines are for making enemies as well as friends. Richie McCaffery revisits the pugnacious Sidewalk via the furious pencil-marks of one of its targets.

One of the most important Scottish literary magazines of the 1960s was also one of the shortest lived. Sidewalk (which ran for two issues in 1960) was formed when the then editor of Jabberwock (an Edinburgh University student publication) splintered away from what he saw as an increasingly cronyist and reactionary editorial outlook, supporting older Scottish nationalist poets and very little else. In his final ‘American’ issue of Jabberwock, Alex Neish, now a local historian and pewter-ware expert, printed the opening chapter of William Burroughs’ The Naked Lunch much to the excitement of his readers, but to the consternation of the press and Burroughs himself, who had no knowledge that Allen Ginsberg had submitted it for publication.

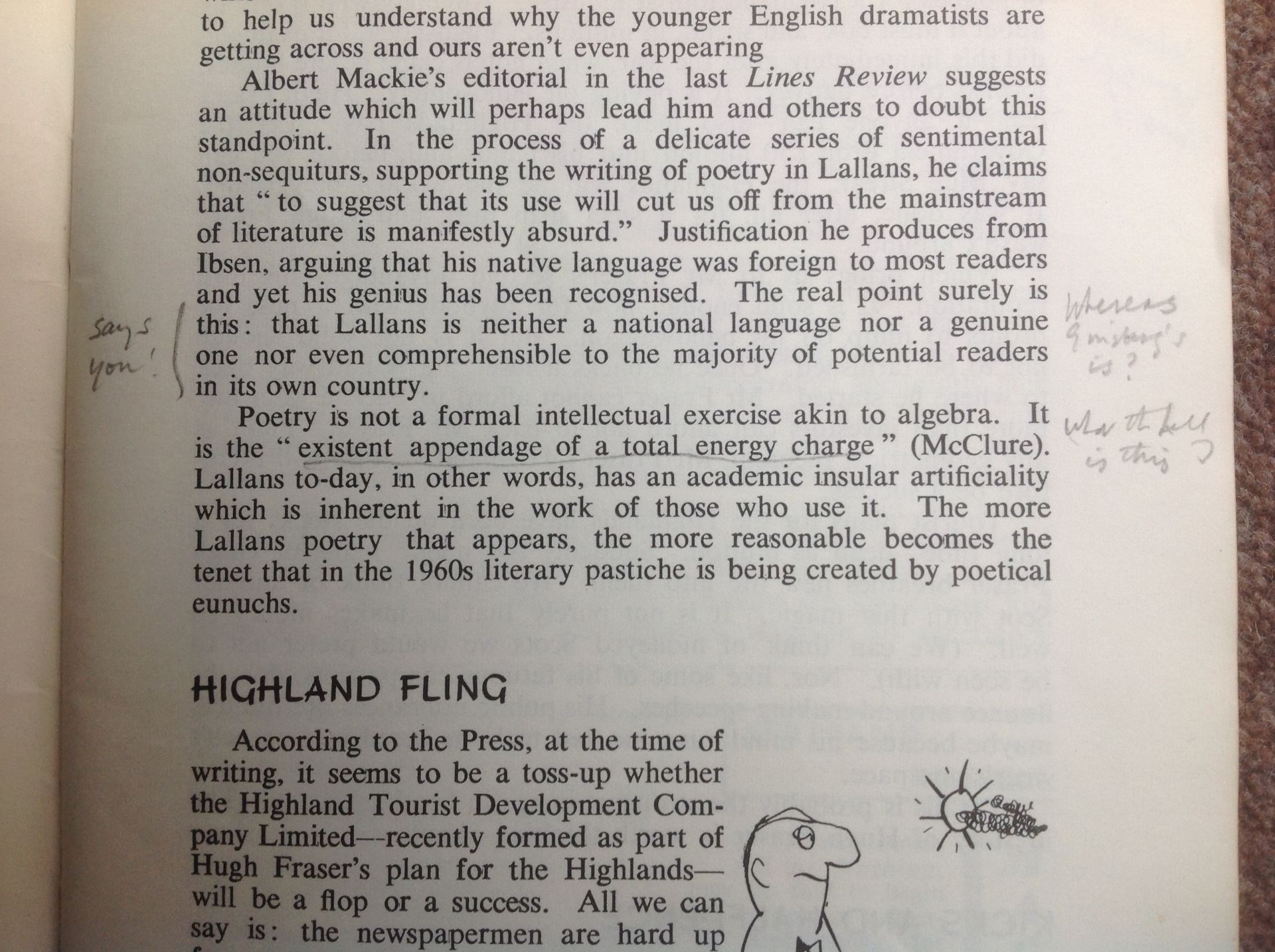

With Sidewalk Neish was free to pursue his own vision, one that was transatlantic and syncretic, not merely a grandstand for the political bloviations of the older kenspeckle Scottish bards. In his valedictory editorial for Jabberwock in 1959 Neish made his thoughts swingeingly unambiguous, saying that he wished to jettison ‘that inferior romantic drivel of misdirected Nationalism which for too long has been a millstone around the necks of younger Scottish writers’. By the time Sidewalk 1 appeared, Neish’s stance had clearly not in any way mellowed, drawing very firm battle-lines in his editorial, guaranteed to antagonise older Scottish writers: ‘Lallans today […] has an academic insular artificiality which is inherent in the work of those who use it. The more Lallans poetry that appears, the more reasonable becomes the tenet that in the 1960s literary pastiche is being created by poetical eunuchs’ (p. 11). Curiously enough, ‘eunuchs’ was one of the favourite insults MacDiarmid liked to throw at writers he regarded as enemies.

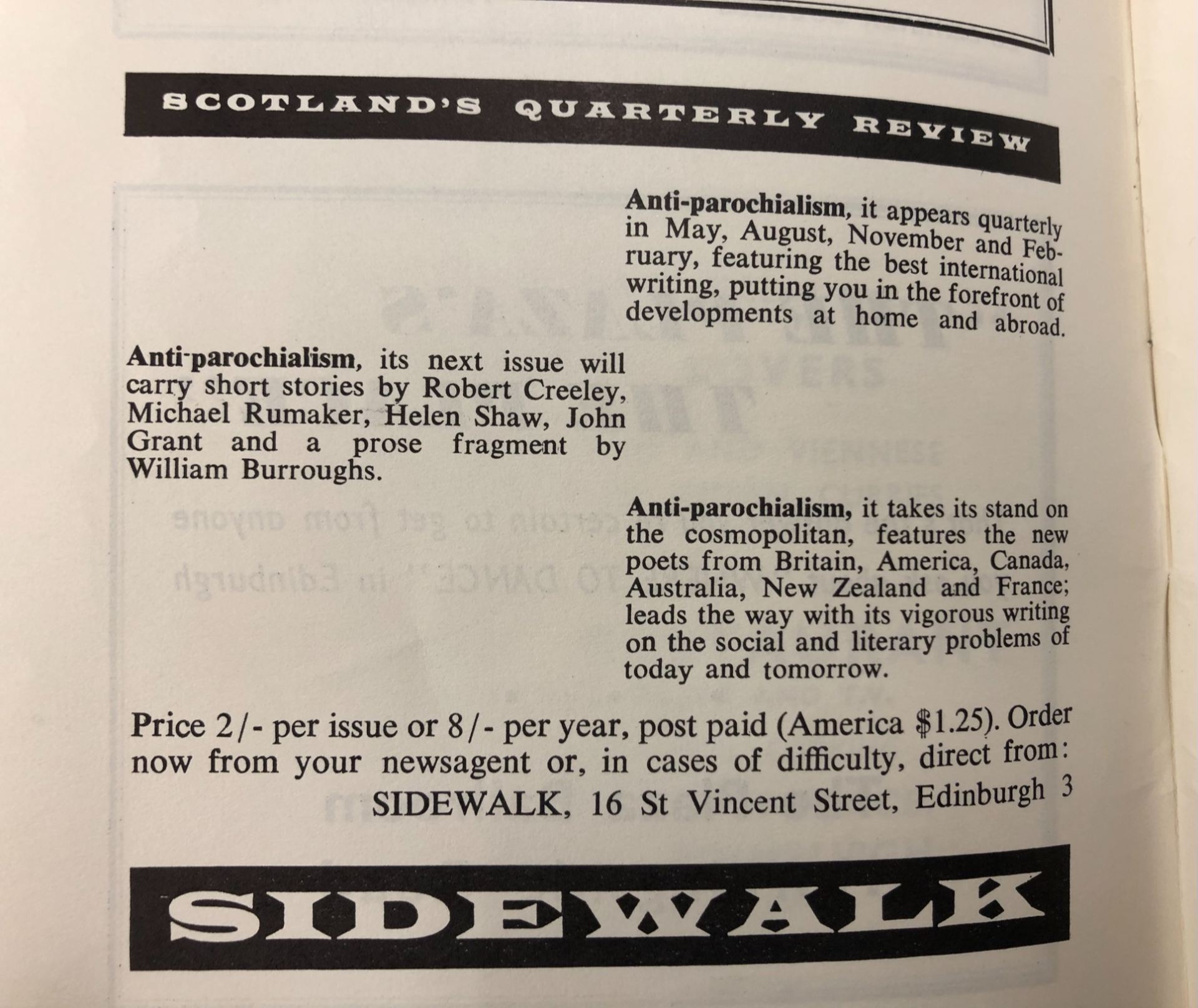

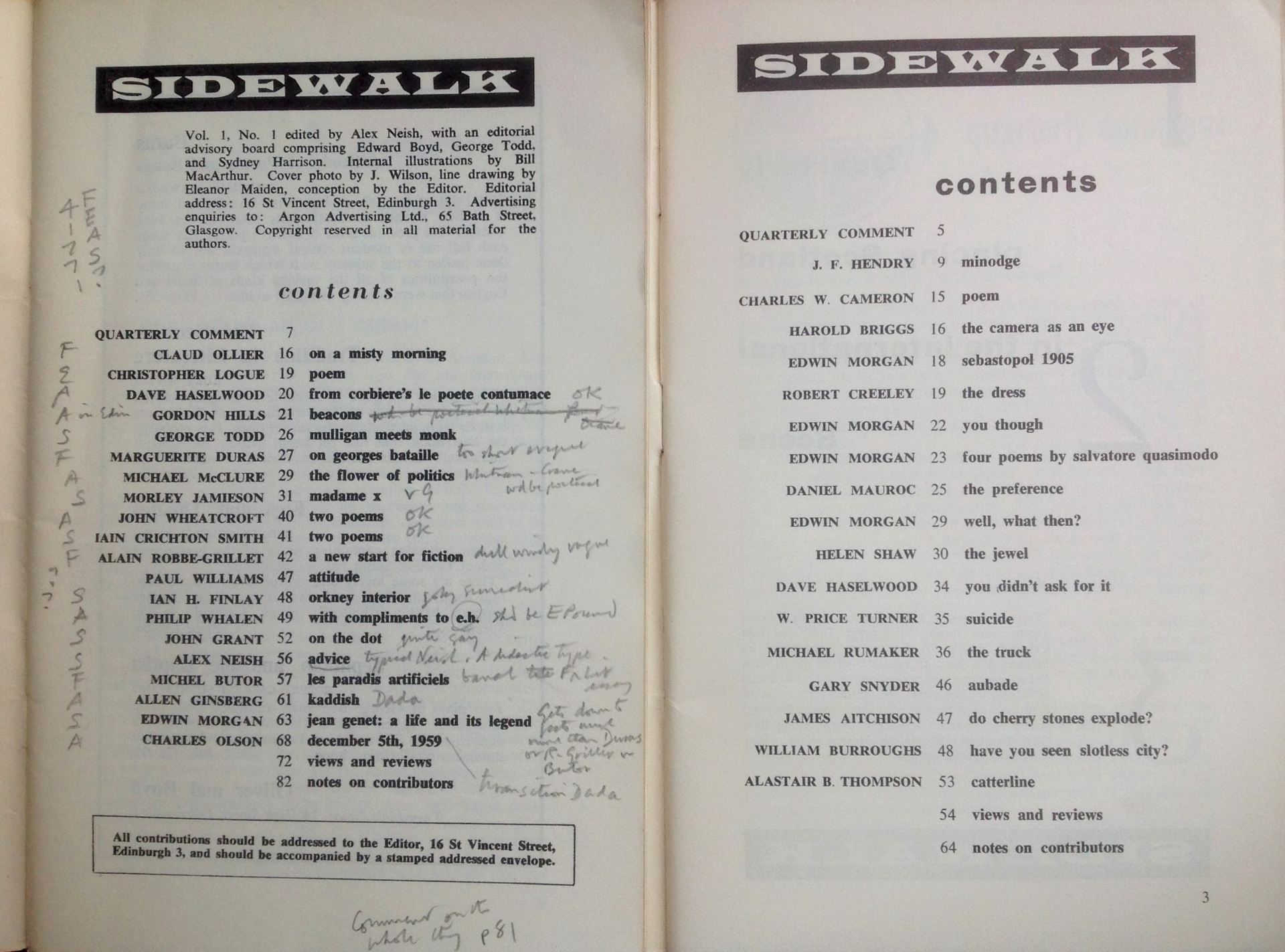

Putting his firebrand rhetoric into action, Neish printed between 500-750 copies of each issue of Sidewalk and the magazine was aimed at an audience most likely to be ‘open-minded’ – university students. The magazine introduced its readers to the likes of Marguerite Duras, Alain Robbe-Grillet, Ian Hamilton Finlay, Charles Olson, Allen Ginsberg, Robert Creeley, Gary Snyder and William Burroughs. This small Scottish periodical was not just tokenistically international, but vitally eclectic, embracing French and British writing, Black Mountain Poetry and Beatnik literature. Let’s just compare the dramatis personae of that line-up with a 1960 copy of Lines Review (a major organ of the Scottish Renaissance). Lines Review 16 has on its cover a reproduction of a woodcut by Moira Crichton depicting Sydney Goodsir Smith, Hugh MacDiarmid and Norman MacCaig all enjoying a guid-willie-waught in The Abbotsford Pub (Rose Street, Edinburgh). The contents are predictable: MacDiarmid, MacCaig, Garioch, Crichton Smith et al. (It’s interesting to note that Lines Review retailed at 1 shilling and sixpence whereas Sidewalk was 2 shillings, at a time when a student grant was perhaps 140 shillings (£7) a week). This is no slight aimed at Lines Review – one of the literary backbones of Scotland for decades – but to show that youth culture and other strands of avant-garde culture needed a room (or magazine) of their own.

Sidewalk might have been a flash-in-the-pan in terms of its lifespan, but it sent intellectual and aesthetic shockwaves through both young and older writers. In 1963, Bill MacArthur, a university student who had acted as an illustrator for Sidewalk, established his own magazine Cleft (which, like Sidewalk, only ran for two issues). Cleft is a seminal small magazine because it not only carried on Sidewalk’s transatlantic and European scope but also introduced concrete poetry and was more tolerant of the veterans of the Scottish Renaissance, like Hugh MacDiarmid and Robert Garioch, both of whom appeared in its pages. This fracturing of an old vanguard and an emergent youth culture is a crucial turning point in the history of the Scottish Renaissance. Jim Burns, in his 1977 article on Sidewalk points out that Alex Neish’s promotion of American writing was not unique in 1960 in a UK-wide context but that it certainly was significant in breaking up the provincialism or favouritism of the Scottish scene: ‘Neish obviously kept his finger on the contemporary pulse’.[1]

This brings us round to Sydney Goodsir Smith (1915-1975), a New-Zealand born poet who converted to writing poetry in Scots in the late 1930s and remained in Edinburgh until his relatively early death. One of Alex Neish’s particular bêtes noires was what he termed the ‘bombastic lackeys of the Nationalist movement’ and he could well have intended this damning phrase for Goodsir Smith who was a fervent disciple of Hugh MacDiarmid’s Scottish nationalist programme for the arts. In 2004, nearly three decades after the death of her husband Sydney Goodsir Smith, Hazel Williamson died and the contents of the New Town flat they shared were sent to auction, including Goodsir Smith’s extensive library which had remained untouched since his death. This meant that for a few years books heavily annotated by the poet would appear all over Edinburgh, in second-hand bookshops and charity shops. It was in the now defunct ‘Old Town Bookshop’ that I bought for £2 Goodsir Smith’s pungently annotated personal copy of Sidewalk . It’s a fascinating time capsule of the clash of values between younger writers like Alex Neish and older Scots stalwarts like Goodsir Smith.

The first thing to note is that he kept this magazine, so he realised it was of importance even if it was offensive to his own tastes. Many of his pencilled comments in the margins are funny but also slightly reactionary. On the contents page he calculates the nationalities of the contributors – four French, at least one English, seven Americans and seven Scots. Many of the pieces are dismissed as ‘Dada’ or ‘transition Dada’ (proving that there is nothing ‘new under the sun’), Ian Hamilton Finlay’s piece is ‘joky’ and Alain Robbe-Grillet’s is ‘dull, windy, vague’ but crucially Alex Neish is deemed ‘a didactic type’. There is also a pencilled remark guiding us to p. 81 where we can find a ‘comment on the whole thing’: ‘But remember, things have been moving so fast in the States that by and large it’s already dated’. There is also an editorial attack on poets who write in Lallans on page 11: ‘The real point surely is this: that Lallans is neither a national language nor a genuine one’ to which Goodsir Smith’s pencil riposte is: ‘Whereas Ginsberg’s is?’

Many of the pieces have comments showing Goodsir Smith’s frustration and bafflement at what he considers the ‘emperor’s new clothing’ of contemporary writing. His umbrage may have also been directed at the magazine because issue 1 carries a particularly wounding review of Goodsir Smith’s latest poetry collection Figs and Thistles by George Todd: ‘This book is aptly named. But there are damned few figs and too many thistles […] this collection bears all the marks of scraping the barrel’. The coup-de-grâce of the review is this observation: ‘One wonders how seriously Sydney Smith takes it. Does he see himself in there lowsing the bands of an oppressed people? It would be better if he showed us he still has his tongue firmly in his cheek and was not squandering his talents on behalf of the parochial, pettifogging fashions which he can be so skilful at knocking’.

Perhaps as a placatory offering, Sidewalk 2 carried a full-page advertisement for Goodsir Smith’s books still in print and a review, again by George Todd, of his play The Wallace. Not quite as acerbic as his review of Figs and Thistles Todd nonetheless dismisses Smith’s play as two-dimensional and simplistic, essentially a ‘good Western’ where the ‘goody’ and the ‘baddy’ are clearly delineated. Sidewalk in this respect is a symptomatic text of its time, giving a clear indication of the fissiparousness of Scottish letters and culture in the 1960s, where a generation that had previously held sway was being challenged younger aspirants and upstarts. Todd, in his review of The Wallace notes that Scottish nationalists will draw parallels from the play to a contemporary Scotland ‘still beset by internal back-biting and schisms of one kind or another’. Sidewalk gave younger writers a platform and the opportunity to discover writing which wasn’t first and foremost Scottish nationalist or Scottish Renaissance-related, and in this sense it broadened aesthetic horizons. However, by attacking the older nabobs of the Scottish Renaissance, like Goodsir Smith, it could be argued that the magazine was merely adding another level of factionalism to the story. Every literary magazine that has a clear identity and outlook also, no matter how much the editors deny it, has a clique, or rather a circle of writers that it is sympathetically disposed towards. By 1960 it was high time someone stuck their neck out to challenge the dominance of ‘The Poets’ Pub’ generation and through the pioneering efforts of magazines like Sidewalk many now essential younger Scottish writers began to break through in the 1960s and 1970s.

[1] Poetry Information 17 (1977), pp. 46-48.

Richie McCaffery is a poet and critic from Northumberland, who completed a PhD on Scottish poetry of World War Two at the University of Glasgow in 2016. He is the editor of Sydney Goodsir Smith, Poet: Essays on His Life and Work (Brill, 2020).