Jenny Turner looks back on the wide orbit of 1980s Edinburgh Review, and its intersecting boys’ clubs and girls’ clubs

In Justified Sinners (2002), Ross Birrell and Alec Finlay’s “archaeology of Scottish counterculture”, Malcolm Dickson remembers the Free University of Glasgow, a loose group that met in the late 1980s to talk about “cross-recognition, kindred spirits, shaking people out of the impossibility of action, behave as if you had power and act as you mean to go on.” He “cringes” to remember one session in particular, at which “an Andrea Dworkin text was read out and the men then had to leave the room to discuss it, then return, and the two groups compared notes. What a slagging!”

In Justified Sinners (2002), Ross Birrell and Alec Finlay’s “archaeology of Scottish counterculture”, Malcolm Dickson remembers the Free University of Glasgow, a loose group that met in the late 1980s to talk about “cross-recognition, kindred spirits, shaking people out of the impossibility of action, behave as if you had power and act as you mean to go on.” He “cringes” to remember one session in particular, at which “an Andrea Dworkin text was read out and the men then had to leave the room to discuss it, then return, and the two groups compared notes. What a slagging!”

I took part in that session, which had been organised by the artist Carol Rhodes (1959-2018), who was at that time working unpaid at the Transmission Gallery and paid – at least I think so – as an assistant to her live-in landlord, Alasdair Gray. Like Malcolm, who went on to edit Variant, I too found the session uncomfortable, though probably for different reasons. You can feel and even know things but have no words for them, and I am evidence that this condition can persist for years and years.

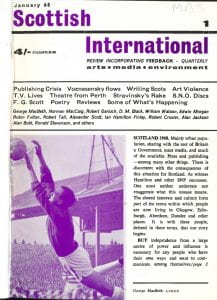

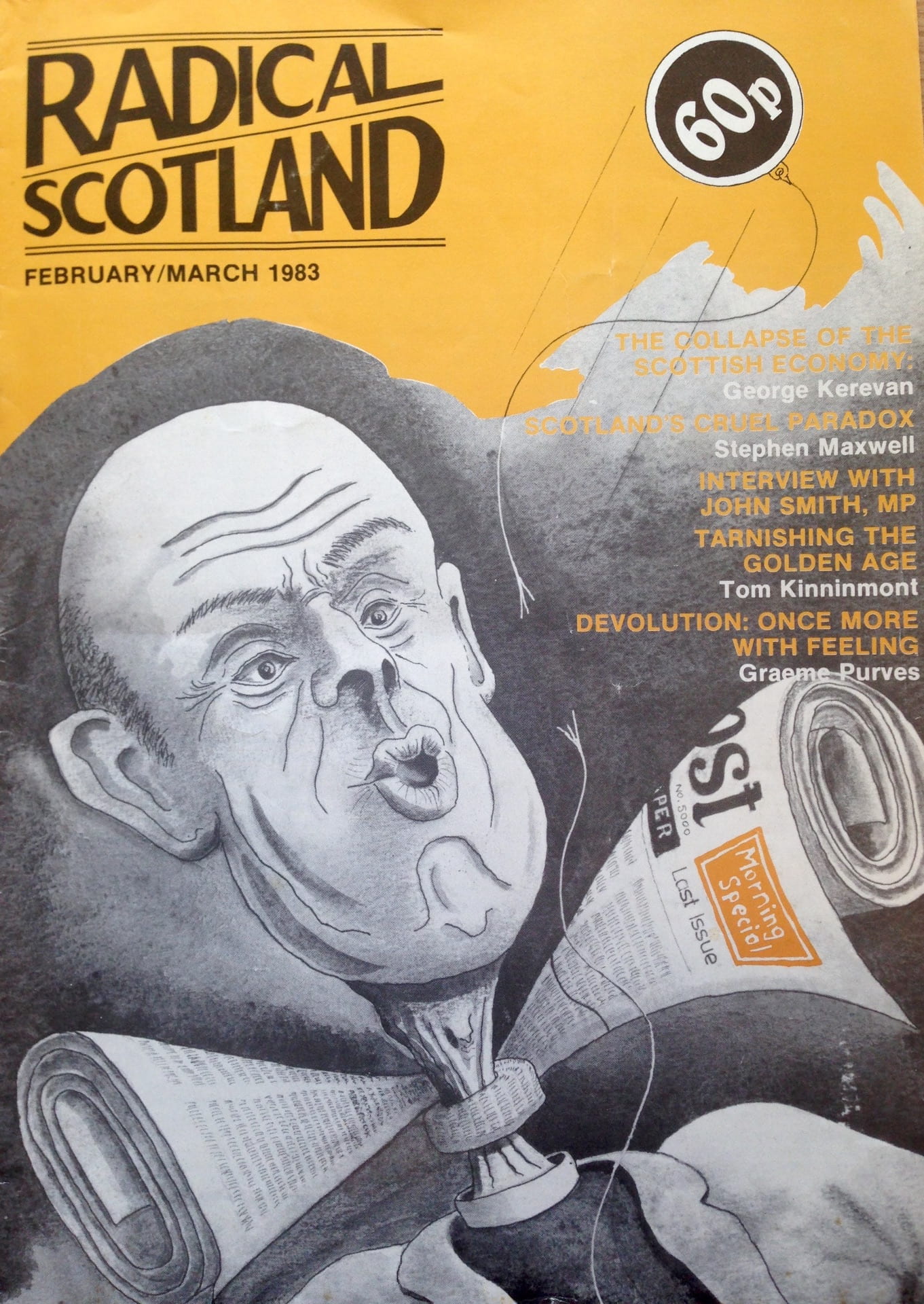

I have been asked to write about my memories of Edinburgh Review, at which I was a regular contributor from 1984 to 1990, and in particular about what a “boys’ club” the wider scene appears to have been. ER and Common Sense and Here & Now and Polygon Books and the Free University of Glasgow, the networks and publications that came together at Self-Determination and Power, the weekend event James Kelman organised with Noam Chomsky in January 1990 at the Pearce Institute in Govan: and it’s just objectively true, and obvious, that all these networks and publications were run by men.

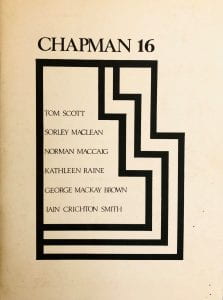

ER was edited by Peter Kravitz then Murdo Macdonald, both of whom also ran the list at Polygon from 1988. Here & Now was Alistair Dickson, Common Sense was Richard Gunn and Werner Bonefeld. Everybody read and admired the emergent work of Agnes Owens, Janice Galloway, AL Kennedy, but there really was a sense that masculinity was where it was at in Scottish literature at that time, in the work of Kelman, Gray, Tom Leonard, Jeff Torrington. In a way it kind of had to be, given that Scotland under Thatcher was all about the breaking of what Beatrix Campbell used to call “the men’s movement”, the old-style organised and unionised industrial working class.

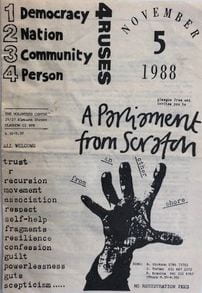

But identity fluctuates, and people are complicated, and a history that considers objectivity an easy matter is unlikely to have much in it of much use. What strikes me now, when I look back on that period, is how much time I spent doing things with women: with Marion Coutts, the artist, writer and musician, designing what I still think is an amazing poster for the 1988 Free Uni Scratchparl weekend in Glasgow (From. An. Other. Shore, it says, between the stretching fingers of an open hand. Respect, self-help, fragments, resilience, confession, guilt, it continues down the left-hand side).

objectivity an easy matter is unlikely to have much in it of much use. What strikes me now, when I look back on that period, is how much time I spent doing things with women: with Marion Coutts, the artist, writer and musician, designing what I still think is an amazing poster for the 1988 Free Uni Scratchparl weekend in Glasgow (From. An. Other. Shore, it says, between the stretching fingers of an open hand. Respect, self-help, fragments, resilience, confession, guilt, it continues down the left-hand side).

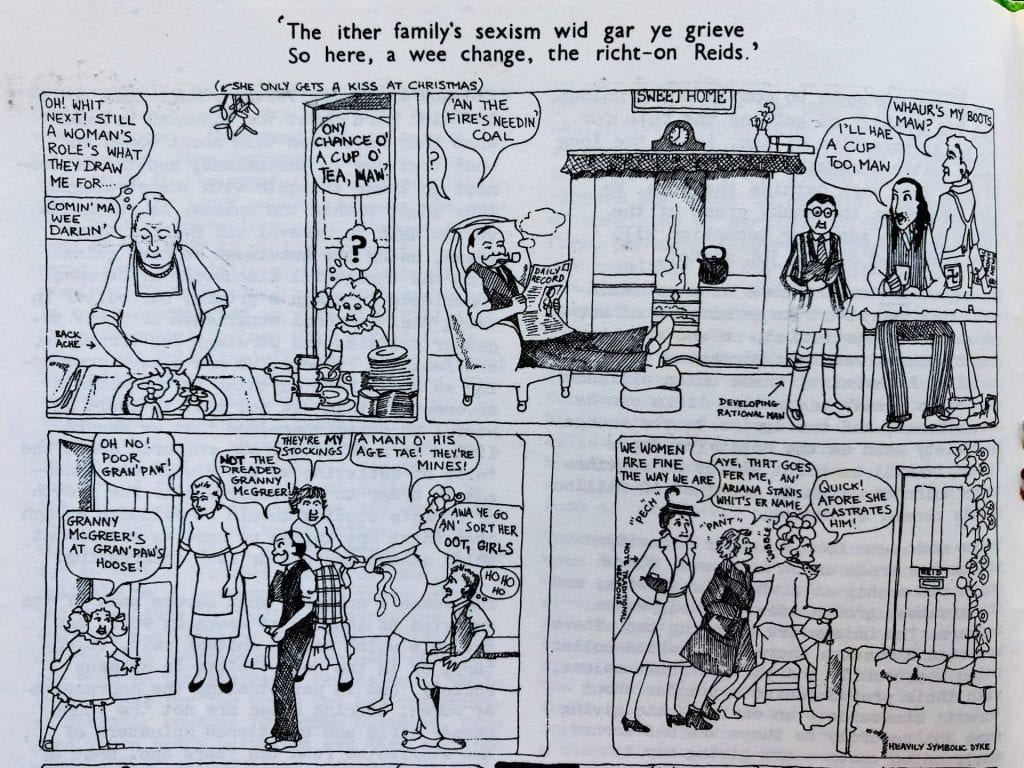

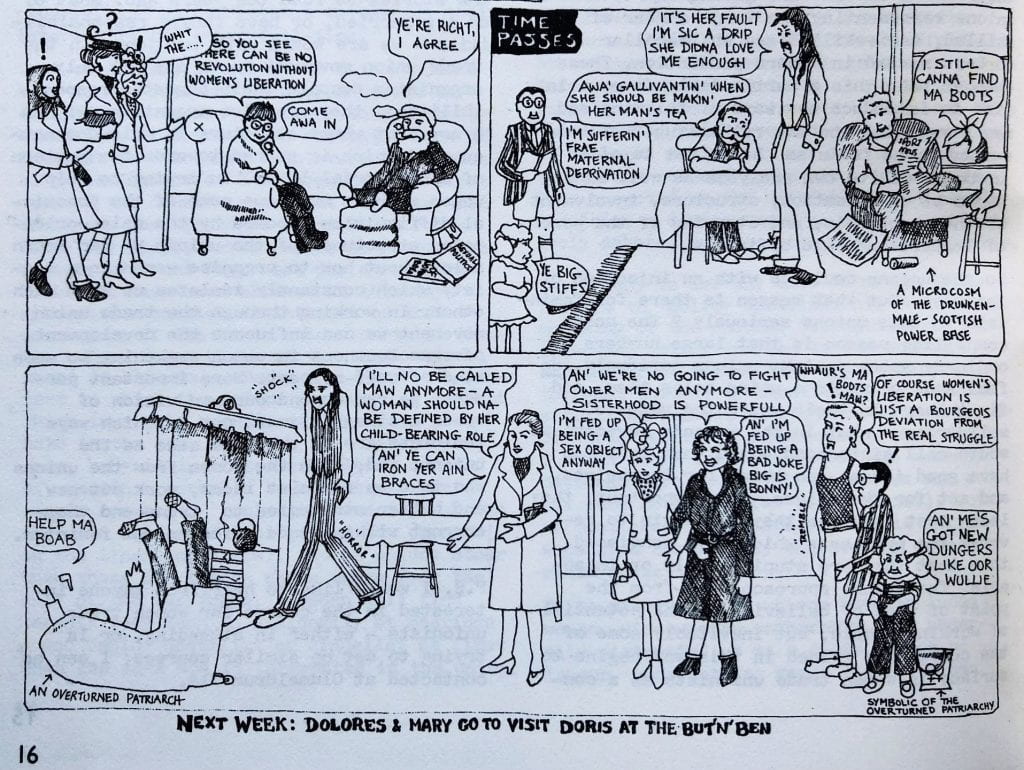

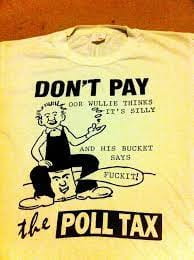

With Kirsty Reid, who edited Liz Lochhead’s Dreaming Frankenstein (1984) and went on to create the superb One Isn’t Paying meme for our neighbourhood anti-poll-tax group, and the even more deathless Oor Wullie Thinks It’s Silly, And His Bucket Says Fuck It.

With Kirsty Reid, who edited Liz Lochhead’s Dreaming Frankenstein (1984) and went on to create the superb One Isn’t Paying meme for our neighbourhood anti-poll-tax group, and the even more deathless Oor Wullie Thinks It’s Silly, And His Bucket Says Fuck It.

I shared flats at different times with Deirdre Watt and Lorna Waite, both of whom edited and wrote for ER, I did Pleasance multigym with Julie Milton, who put together the first Original Prints anthology of Scottish women’s writing. Sue Wiseman, now Professor of Seventeenth Century Literature at Birkbeck in London, was the first and best of ER’s critical writers on Kelman. Marion Sinclair, now head of Publishing Scotland, started at Polygon as its first proper staff person in 1988. So yes, there were many boys’ clubs going on across the central belt in the 1980s, but they interacted and intersected with the girls’ clubs. The interesting question is why the boys’ clubs get remembered more, and more formally memorialised, and the girls’ ones don’t.

The Free Uni, Malcolm remembered in his article, also aimed to set up an actual clubhouse: “a place that didn’t shut at 5pm and which didn’t require you to spend money”. The Double Deckers, I called this, after the children’s TV show, seeing myself, I think, as Gillian Bailey. Except that nothing like it ever happened, because opening and maintaining an actual built space necessitates not just talk but steady material resources.

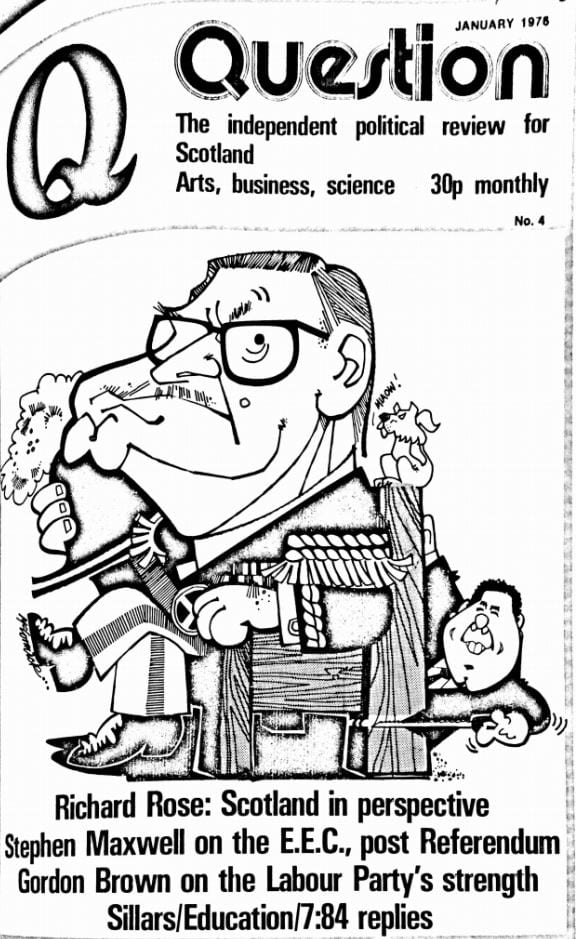

In the podcast interview he contributed a few weeks ago to the Scottish Magazines Network, Murdo talked about how Edinburgh Review and Polygon would never have published the sort of work they did, would probably not have existed, without the institutional anomaly of the Student Publications Board at Edinburgh University, a sort of student club that as well as doing pub guides and the weekly student paper, had the resources to take on proper, important book-projects: Gordon Brown’s Red Paper on Scotland (1975), Kelman’s Not not while the giro and The Busconductor Hines (1983-4). Peter, Murdo, Kirsty, Deirdre, Lorna, Julie and I had all been students at Edinburgh University. All of us started out with Pubs Board as students in our different ways.

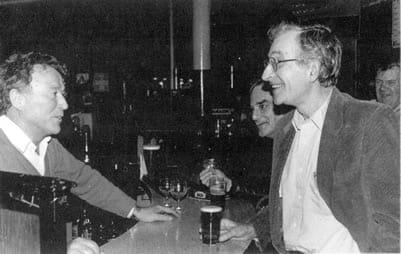

Here’s the thing, though: on who, and what, sticks around enough to get properly remembered. ER would not have been ER without the vision and know-how of Peter Kravitz, and nor would Polygon nor the Free Uni; and if you read up on old interviews with Galloway and Kelman, you’ll know how much such writers say they owe to him as well. Then along comes Murdo with the Democratic Intellect and the Scottish common-sense philosophy connection, and thus all those extraordinary cross-disciplinary imprints, Sigma, Mundi, Determinations, all those beautiful white paperback originals with their spinal colophons and their deep French flaps. Even as very young men, and Peter would have been 23 in 1984, Peter and Murdo seemed always fully formed in a way the rest of us weren’t. It is not, I hope, to diminish their brains and work to notice that much of this difference was socio-economic.

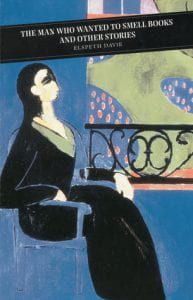

Both had English public-school educations behind them, and huge collections of old books, and most importantly, had flats of their own to keep them in. They were men of property, they drove cars, they knew how to handle money and they used it in adult, expansive ways. When I was Murdo’s lodger, I remember, I used to hide out scared in my room when he gave tea-parties for venerable friends such as Halla Beloff, George and Elspeth Davie. And I can now laugh – almost – at how bitterly I remember Christopher Logue being slow to get a piece in, and Peter sending him a chocolate cake from Fortnum & Mason. He never sent me a chocolate cake from Fortnum & Mason! Not a Tunnock’s Teacake, nor a Cadbury’s Crème Egg!

I did get paid, though: £50 for my first ER piece, I remember it clearly because I donated it to the relief fund for the famine in Ethiopia. I had a strange idea at that time that it was wrong to take money for writing, I remember explaining it to my mother, though I can’t remember how I put it. It may have had to do with claiming dole at the time and also housing benefit. For a couple of years I also had Scottish Education Department grants. I don’t remember how much I got for subsequent ER pieces, though presumably it was about the same. I do remember that after that first splurge with charity, I started keeping the money to myself. The government’s Enterprise Allowance Scheme gave you £40 a week for a year if you put up £1,000 of savings, so I did that and set myself up as a journalist. I often wish that I hadn’t, or that I had got myself out of it later. But for better or worse I didn’t, and here I am.

I was surprised, the other day, while talking to one of my Labour Party friends near where I live in south-east London, to find that this friend doesn’t think of me – as I think of myself – as posh. I’ve been a homeowner for nearly 20 years now, I write articles for the London Review of Books, I have loads of books and the shelves to keep them on: I never expected such prosperity when I was younger, and I don’t think I especially deserve it. Or that anyone deserves anything, good or bad. But I do think: historical forces, how they tear through people, how they’ve flung me up, at least for the moment, and what burdens they are dumping on the young.

It’s great to get to contribute to this project, to think that people are interested in things I know about from 30 years ago, getting on for 35. It’s nice to stand outside yourself for a moment, to see yourself, a little candle, a tiny part of something bigger. Someone reading this, maybe, will remember more than I can from Carol’s Andrea Dworkin session. What was the slagging, who did it, what was said in it? Was it taken seriously, and if so, how, and by whom?

Jenny Turner was born in Aberdeen and educated at the University of Edinburgh. She is on the editorial board of the London Review of Books, and published a novel, The Brainstorm, in 2007.